“It’s all very well for me to tell myself there are no provincial cities any more and perhaps there never were any; all places communicate instantly with all other places, a sense of isolation is only felt during the trip between one place and another, that is, when you are no place.”

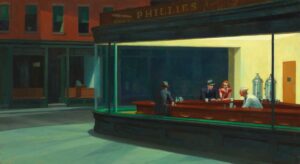

North Yorkshire, England. The first abortive story of Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller is a noir-style mystery in which you could cast Humphrey Bogart—a stranger waits patiently with a briefcase for a train that gets further and further behind time before, finally, it never arrives. Calvino could have set it no better place than in a smoke-wreathed train station inhabited by fringe characters who take center stage and a central character who is pushed to the fringes of his own story. It is Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks with rails, a place of transience and anonymity, embodying what the French anthropologist Marc Augé defined as a “non-space.”

In 1992, Augé outlined the differences between what he calls anthropological spaces and non-spaces in the imaginatively titled essay (and subsequent book), Non-Places: “Anthropological place is formed by individual identities, through complexities of language, local references, the unformulated rules of living know-how; non-places create the shared identity of passengers, customers or Sunday drivers.” Anthropological places are easily identifiable—they have the three characteristics of being “places of identity, of relations and of history.” Non-places are their opposite. They don’t have enough significance to be called spaces; they anonymise the individual and have no living relationship to the setting, people, or history of their location.

Calvino makes no attempt to locate the train station. Its location is entirely immaterial—non-spaces are international, placeless, interchangeable. A train station is much the same in Paris, Denver, Buenos Aires or Manchester. And since Augé first identified them, non-spaces have begun to occupy more and more of our built environment. Taking advantage of a wave of regeneration and rebranding that took place in post-industrial cities during the late 2000s they have slowly sterilised our spaces, replacing individual, localised businesses and spaces en masse. Nowhere is this most true—or more apparent—than in Britain’s first successful post-industrial city, Manchester.

The regeneration of post-industrial cities, as all regenerations are, was an act of both preservation and destruction. In a phenomenon repeated around the world, as formerly dominant industries died, along with them went a city’s sense of identity, an identifiable uniqueness: Pittsburgh and its steel production, Manchester’s textiles, Detroit’s cars, Bilbao’s mining. A Detroit-built car did not just drive the economy of a city—its manufacture influenced the makeup of neighbourhoods, the industrial architecture, the entire cityscape.

Emptied of industry, cities had to redefine themselves economically in order to survive. It was a business strategy—one born in corporate culture, not local—that took advantage of the global economy to rebrand and reposition a location as a destination. No longer were the city’s products marketed, instead, the city itself became the product. Instead of exporting goods from the city, people would import themselves to the cities as visitors, global businesses, and a workforce to service them both. Along with this would come international and transitory capital.

As it so often does, architecture became a tool of the economic. These city-wide rebranding projects are often launched in the same way, with leaders turning to famous international architects to provide a flashy showpiece, to replicate “the Bilbao effect.” The “icons” of Manchester’s Lowry and the Imperial War Museum North, both housed in Salford Quays, have both rightly been decried by such notables as Jonathan Meades and Owen Hatherley for their unimportant, unrepentant, unimaginative lameness.

The practical purpose of these showpiece buildings is immaterial—their figurative meaning offers the value. Whatever the building, whomever the architect, wherever the city, it was a physical manifestation of the city’s conversion—a sculptural rendition of Saul on the road to a very profitable Damascus. Statement pieces all share a meaningless, rootless architectural style that is both non-relational and non-historical, designed to appeal to the international, not to the local.

It is of course entirely appropriate, entirely symbolic, and entirely convenient that the architectural fabric of former industry is usually the first to be regenerated into non-space. In order to house new workers, attract new visitors, and host new business, new buildings are necessary. Big business requires big spaces, and the vast spaces of docklands or large industrial areas offer the necessarily vast scale. Added to that is the fact that the space is cheap, offering stellar profit margins, and that it is readily available; building permits and permissions are entirely within the gift of city leaders, and redevelopment brings political bonuses as well as jobs. At their height the Manchester Docks were the third busiest port in Britain, but the port enclave, 35 miles inland, was slowly killed by containerisation and deindustrialisation before being closed in 1982. Now it is an exclusive entertainment and luxury housing complex, housing BBC executives during the week and the city’s homeless on the weekends, a modernist mausoleum unencumbered by genuine human interest, agency, or community.

The Lowry and IWM North set the tone for the rest of the city to follow, establishing an architectural precedent for similarly remote, top-down internationalism. The vernacular of the non-space does not lend from the local library, and this is entirely necessary. Augé’s non-places don’t just require a dislocation from their immediate surroundings but are borne of a need—the need of what he termed “super modernity”—to move vast quantities of both capital and people. They are designed to reduce the individual’s identity to whatever they are doing in the non-space—that is, to consumer or commuter. Non-spaces are designed to engender as close to a frictionless existence as is possible by reducing interaction to the absolute minimum, because that is the most profitable way of designing a space.

This process of regeneration erodes the number of spaces that differentiate cities from each other. If provincial cities do exist, then the process of regeneration is making it more and more difficult to tell them apart. The redevelopment of former industrial areas is a reification of the city’s transition—repurposing whole neighborhoods previously dedicated to industry serves to sanitise the city’s past, to gentrify its reputation. No longer are there dirty, soot-blackened factories or well-worn wharves, the rotting corpse of industrialisation. Regeneration renders the historical fabric of the city inessential. As a result, few buildings survive the process.

But the replacement process is not limited to shiny, indistinguishable modern apartment and office buildings. The process of regeneration means an influx of international, transitory workforces in place of former communities. As a result, any space that provides a locus of historic significance and meaning to local communities is likely to be lost. Old, historic, or unique businesses are therefore marginalised by the gradual erosion of their customer base. That these become non-spaces is largely inevitable. How can you create places that shape the identity of the community if there is no community? The answer is, of course, that you don’t.

Perhaps nowhere is this trend more advanced than in Manchester’s much-vaunted hospitality sector. Whether drinking in the false bohemianism of the Northern Quarter, eating amidst the abject soullessness of Ancoats or weekend millionairing in the industrial riviera of Castlefield, you are at all times assaulted by the newness and shiny placelessness of your surroundings. These bars and eateries may be Manchester’s biggest draw, but, like Calvino’s train station, there is little placing them there.

But these are not solely the result of a replacement of local businesses with interchangeable, international outlets. Large chains are often too large and too remote to immediately capitalise on the emergence of newly-in vogue neighbourhoods. This is a gift to entrepreneurs on the ground. Manchester’s hospitality sector is notable for its diversity and high number of small, local operators. But the spaces they create still tend to be non-spaces, with no living relationship to the locality, relying on a marketed alternativism.

Those entrepreneurs take their design inspiration from what they know. Many of Manchester’s new businesses have been opened by young people who have been imbued with the spirit of Manchester’s now 40-year long regeneration project. They are—and always have been—only exposed to non-spaces. They copy what they know, and what they know is, in Owen Hatherley’s words, “a city which has dedicated itself to the service industry and the property market, bolstered by the propagation of an ideology of culture and creativity, where it matters little what the actual cultural product is.” The result is a coterie of synthetically modern places that make up the bars and eateries of Manchester’s much-vaunted gastronomic sector.

The process of regeneration reduces the historical fabric of the city from a living manifestation of the city’s breathing virility to an occasional reminder of what once was. As the fabric of Manchester has gradually given itself over—willingly and profitably—to non-space, its anthropological spaces have accordingly reduced. Its anthropological sense of itself, too, has reduced. Faced with this lacuna, the city has turned to branding to market itself, and to the near-ubiquitous Manchester Bee. It is the inheritor of Manchester’s fine and proud history of tedious myth-making, the soundbite of the city and its perpetual marketing campaign.

The Manchester Bee attempts to both reference and replace what Manchester used be famous for—mills, industry, work—in the minds of people to help create a collectively false memory and meaningless consensus for the city’s future. It is meant to reference, to supplement, but also to circumvent. Manchester doesn’t do smog or spinning jennies anymore. It’s a friendly city. Come on in.

Manchester has become so meaningless that the Bee is entirely necessary to act as an identifier of location. Having replaced community with consumption, it is no longer a space for living but for visiting, either long-stay or short-stay. The Bee it not so much a branding exercise as a catafalque. Augé wrote that “it is the coexistence of two worlds, chimneys alongside spires, that makes the modern town.” Manchester no longer has either. It has the Bee.

Header Image: IWM North

4 comments

Martin

The contrast defined by Augé is sloppy if not narrowminded: “non-places create the shared identity of passengers, customers or Sunday drivers”.

Leave aside the drivers (whatever they are supposed to signify), the other two alleged negatives reveal the theorist’s “snapshot” mentality, oblivious to the “movie” of humans moving through time. Famous restaurants, diners, hangouts, etc. develop a “space” reputation due to the rhythm of regular customers.

This could even happen at convenience stores, as most of us have noticed to some degree or other. And it certainly can happen when commuters ride a train at the same schedule each day, often habitually sitting in the same car.

Ironically, the starkness of his contrast belies the importance of time to space, as indicated by countless appeals to *tradition* in FPR’s essays about localism.

Rex Bradshaw

My patriline traces to 17th-century Lancashire, an area that I now gather is basically Manchester suburb. I’ve never been to England, but it is sad to contemplate.

Leslie Forsyth

Lancashire is very far from being a Manchester suburb. Perhaps you should visit. This article is an over-the-top rubbishing of a vibrant city.

David Ryan

Tom, I enjoyed this. You mention how large corporations gradually erode the customer bases of historic businesses. One of the things that frustrates me is that we all have a hand in making that happen, with every purchase decision. No one likes it, but not enough of us change enough of our purchasing behavior. How do we change that? How do we connect people’s daily decisions with the “inevitability” of the fall of the things they love? How do we build an ecosystem of local businesses that make it as easy for people to patronize as the mega businesses?

Comments are closed.