I’m behind on everything. Chores have piled up in my distraction. Summer thunderstorms and bright sunshine have let the woods creep onto our property, and there’s more work to be done than seems possible.

Tonight, once I close the laptop, I’m going to suit up. Venturing onto the homestead to do the normal round of chores will involve swapping into another outfit, fueling up power equipment, and lots of hacking and slashing. My outerwear has been pre-soaked in permethrin to guard against deer ticks. I’m going to use a gas-powered “brush cutter,” a weed whacker that uses a spinning blade to pulverize plant matter.

It feels like I’m going to war.

In a previous essay, I described how ten years of homesteading had changed my political philosophy: I practice a sort of country bumpkin anarchism. But beyond the triumph of a suburbanite discovering the boondocks is a harsh truth: as we shape the land, the land can easily shape us. The romance of the countryside flees when it comes time to push back against nature.

It wasn’t always this way. My wife and I went out of our way to work organically. We did surprisingly well, at least until this year.

In this essay, I’ll talk about our history of using hand tools, organic pesticides, and other “natural methods,” what made us change our mind about using inorganic methods, and what I’ve learned about age, responsibility, and externalities.

Your skin, your bones, your virtue

The psychedelic retelling of a 14th century story, 2021’s The Green Knight contains a haunting speech that I can’t seem to shake. Wondering aloud why the titular knight of the film is the color green, one of the characters launches into a chilling monologue that ends with the following:

When you go, your footprints will fill with grass. Moss shall cover your tombstone, and as the sun rises, green shall spread over all, in all its shades and hues. This verdigris will overtake your swords and your coins and your battlements and, try as you might, all you hold dear will succumb to it. Your skin, your bones. Your virtue.

Anyone who has ever lived at the edge of civilization knows the truth of this speech in their bones. It takes almost no time at all for nature to erase everything you’ve built. Sooner or later, the green comes for us. And no matter how much energy you have, the green has more.

Keeping nature at bay, through any means necessary, runs deep in our consciousness. Rattlesnakes are extirpated in my region because, as the more-than-90-year-old woman down the street tells me, they killed rattlesnakes on sight back in her day. My county and the state Department of Agriculture quietly dumps pyrethrin-based insecticides by airplane to kill black gnats, midges, and mosquitoes, all in an attempt to forestall outbreaks of West Nile and other diseases. Elk reside in Pennsylvania, but only in the far north central mountains of the state, even though their range included my southeastern corner of the state. Reintroduced after full extirpation over a century ago, these transplanted Yellowstone elk immediately left the mountains to level farmers’ cornfields. The Game Commission had to mediate the wildlife conflict battle. They won’t ever finish trying to keep the massive elk from eating crops and farmers from shooting them.

When my wife and I started our rural homestead, we were suburbanites with a lot of ideas. For one, we’d do everything organically. No question. Second, we’d endeavor to only use hand tools. Scythe, sickle, spade. We’d become experts in the old ways. And third, we’d limit outside inputs. Among other ethics we’d imposed on ourselves, these three were in line with the permaculture principles that guided our work. We thought it was our responsibility not only to our own land but also to our community and the planet: as landowner Doug Duren puts it, “it’s not ours, it’s just our turn”.

Nature humbled us. When we started our podcast to record our homestead adventures, we spent a lot of time recounting our failures: acres-worth of organic crops lost to pest damage, groundhogs digging tunnels under our outbuildings, and, probably the most notorious story around here, a mouse breaking into the garage to eat my wife’s tomato seedlings, just a few days emerged from the soil.

We kept on grinding. Ten years later, we’d managed to only use two gasoline-powered tools: a chainsaw and a chipper-shredder. Ten years later, the strongest chemical we’d used was Neem oil. And then, ten years after we’d started, we had our second child.

The resolve breaks

We love having kids. But as relatively old parents at 38, we did not know the blessing of time until we didn’t have any.

Prior to our second child coming into the world, we managed to keep a few parts of the homestead organic, using hand tools, and following those permaculture principles as best we could. Here are a few of the areas where our resolve broke.

Taming the Back 40: a scorched earth policy

Every homestead has a “back forty.” It’s the part of the property furthest from the living space, or the hardest to access. Where the wild things are, so to say.

When we had our firstborn in 2021, the back forty started to slip. We’d been controlling it with a scythe and a reel mower, and that worked, but only if you were relentless. Even then, weather and time might not cooperate. But worse were the invasives.

We have a few pernicious invasive plants in Pennsylvania that seem impossible to manage. The species that gives me waking nightmares is an East Asian transplant called multiflora rose. Resembling a blackberry on steroids, multiflora grows fragrant flowers and “rose hips,” fruits around the size of a pine nut. Pollinators love the aromatic flowers and thus hundreds of fruits appear each year (a good time to plug my piece about the problem of invasive pollination). Cut the plant to the ground and it will spread by rhizome, shooting up in a dozen places. Multiflora loves to intersperse with useful species like mayapples, raspberries, and blackberries, making it difficult to extract. When you do go after it with a cutting device, multiflora seems to strike back at you: its thorns are fearsome and will go right through my heaviest canvas pants. The taproot, according to one landscaper I know, digs ten feet down. She ties a tow strap to large specimens and pulls them out of the ground with her truck on wet days. A scythe or a brush knife seem powerless against multiflora.

Another nightmare annual is stilt grass, also from East Asia. Resembling a tiny bamboo plant, it loves disturbed soil, shady spots, not-so shady spots, bad soil, rich soil, and long walks on the beach. I suspect that the seeds persist for years in the “seed bank,” the natural load of seeds within the soil system. I say this because my wife and I have pulled huge strands of stilt grass only to watch it return in the exact same place without hesitation.

The list of invasives goes on: Japanese barberry and Japanese knotweed from Asia, bitter dock and creeping jenny from Europe, and more. The 20th– and 21st-century invasives make dandelions, a colonial-era invasive, look like hippies at the blitzkrieg. New invasives now sit on top of 15th-century European invasives and the combination levels everything intentional about the landscape.

2023 was the year I bought a commercial brush cutter, more or less an enormous weed whacker. It cuts almost anything under 3 inches and cuts my time spent on any problem in the yard. After using a scythe, the brush cutter feels like an extravagance. I’ve used it for about 20 or 30 hours this summer, and I still feel like I’m cheating at life.

I use trimmer line sparingly, since I figure it flings microplastics everywhere (there are some biodegradable options on the market I intend to try). But it’s hard to feel bad about that: I also learned in the last two years that children create microplastics almost as readily as drool. I’ve thrown out more sippy cups than I can count, and one giant plastic bouncing toy is probably worth a lifetime of trimmer line. I live with the guilt but continue to use the brush cutter against the relentless tide of green.

Beekeeping: Fighting an uphill battle against a pancake-sized mite

An old beekeeper told me that back when he first started keeping in the 80s, 5% losses, or one in twenty hives, was a dismal failure that would get you accused of being a neglectful beekeeper. Today, annual hive losses are around 50%. You will likely lose half your hives each year.

I read many beekeepers before I started, but Michael Bush’s work spoke to my permaculture interest: he believes in breeding better bees instead of using chemicals like acaracides. These mite-killing chemicals combat varroa destructor, beekeeping’s most pernicious pest. As an invasive from East Asia, it has killed countless honeybees and shows no signs of stopping. Think of it as a tick that attaches to bees and sucks their vital bodily fluids, while also passing on diseases. It’s one of the largest mites in relation to its host. Imagine a tick as big as a pancake attached to you and you can picture a varroa mite’s problem for honey bees.

And Michael Bush is right that better genetics are the only way out. But breeding is a labor-intensive process not available to most hobbyists. And I am not made of money. It’s $125 for a package of bees, and you need to buy at least two to have an apiary. I do not have the time or the money to breed better bees. I would be done with beekeeping if that was required of me.

This year, instead of using the many organic control methods—various types of organic acids including oxalic and formic, and, my favorite organic control method, which is doing nothing—I went inorganic. I used amitraz. There’s warnings all over the package about certain death from mishandling. But I have gone organic with beekeeping, and I have lost plenty of hives.

This is an experiment for me. For all I know, I’ll lose my bees again this year. But it’s worth a shot.

The Human Variety of Bloodsuckers: Keeping the ticks at bay

In 2022 I had both COVID-19 and Lyme disease: Covid in May and Lyme in July. I literally had “Corona with Lyme,” like some kind of walking, talking meme. It was an unpleasant experience and, given the option of getting one or the other again, I’d take Covid any day. Antibiotics cleared the Lyme up, thankfully.

My portion of Pennsylvania is ground zero for Lyme disease, and the ticks carry plenty of other nasty bugs. Deer ticks infest everything. This year was particularly bad, due to the mild winter, meaning we were seeing the deer ticks as early as March. Hot and dry weather seems to drive them off, but daytime temps in the 60s that persisted from February through May were perfect for them to run around. All signs point to Lyme disease becoming more prevalent (though I wonder if that is just an improvement of diagnostic criteria). Other tick-borne diseases are on the rise as well.

Stopping the little buggers seems impossible. Deer ticks can be as small as a poppy seed and attach anywhere from your hairline to your groin. Given the little kids in the house and the amount of outside chores I do, the trend has sent me spiraling into anxiety.

This year, I brought out the big guns. I maintain an outdoor outfit sprayed regularly with Sawyer’s permethrin and then given a good shot of DEET as well. I wear rubber knee-high boots everywhere, also treated. I have let as much light onto the ground as possible and kept grass short, to not give the ticks any place cool and damp to hide. I’ve thought about buying “bait stations,” which are food dispensers equipped with permethrin brushes, designed to inoculate animals like mice and deer that carry ticks. You could say I’ve made dealing with them a minor obsession.

But as someone who cultivates pollinators, the exercise depresses me. I’ve prided myself on maintaining a property that pollinators love. We’ve never done a survey, but I swear I see a new variety of bee or wasp every year visiting our Mountain Mint or monarda. But if this homestead is to continue, I cannot afford to have it be dangerous. I am hoping that recent efforts like vaccinating mice and a Lyme vaccine candidate in the works can put a dent in this problem. I’m crossing my fingers and hoping that within a decade, this disease is not the problem it’s been.

Keeping the Cool: The Year We got Air Conditioning

When I used to tell people that we lived in Pennsylvania without air conditioning, I got one of two responses: incredulity, or sage nods. The latter group was usually older and remembered a time when air conditioning wasn’t available to them. Most people just thought we were crazy. Pennsylvania is not a southern state, but the heat and humidity are no joke. It’s not just us: At the Constitution Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, Pierce Butler’s wife went home to South Carolina saying that Philadelphia was too hot.

We thought living without climate control in the summer honed our edge. Air conditioning made you soft, and believe it or not, you do adapt to the heat after a while. Otherwise, how did homo sapiens ever get out of the African continent? How did anyone live in New Orleans before the 20th century? And the energy savings were obvious. For ten years, we did our part for the environment.

This year was different. The summer has been mild, by all counts. As I write this in August, we’re hovering in the low 80’s during the day, which is unheard of for late summer in PA. But one event screwed it all up: the Canadian wildfires.

Suddenly, and in a smelly, obnoxious way, keeping the windows open wasn’t an option, especially with two kids under two in the house. Without the open windows, the house started to turn into a furnace. I dusted off a window unit we had in an old apartment some twelve years ago and installed it, cooling things down and getting us through what seemed like endless smog alerts for the East Coast.

We have a real problem now, which is that our young son thinks he’s a popsicle: he loves the air conditioner and will lay in his room with it on full blast, airing out his armpits. We’re all addicted now. My edge is long gone.

Inorganics, the solution I didn’t want

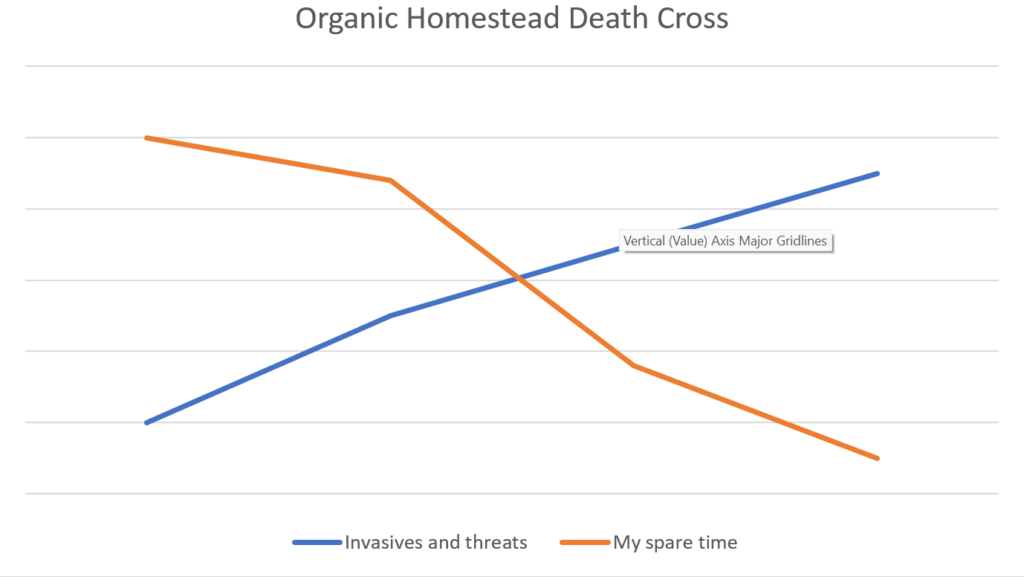

In economics, a “death cross” is a phenomenon in stock trading where the short-term price falls below the long-term average price. On the chart, you see the two trendlines cross one another. It’s usually a signal that bearish times are ahead.

My “organic homestead death cross” looks like this:

When thinking about the four problems from the last section, pictured with the blue line, there’s a clear trend. Two of the issues deal primarily with invasive species, namely invasive plants and varroa destructor (honey bees are technically invasive, but I like honey). The third, ticks, could be said to be a matter of invasive species given that ticks are expanding their native range and some of the new diseases found in the ticks seem wholly original. The fourth, the Canada wildfire smoke, also feels like a Canadian invasion. When it comes to the orange line on the graph, having two kids under two seems impossible even without the homesteading, and my time has evaporated.

So as you can see from this incredibly scientific chart, my spare time has decreased significantly, while threats and invasive species has climbed over the same period. And here I am.

What I’ve realized is that the problem inherent in keeping an organic homestead are competing externalities. In the case of my missing time, the externalities include the hidden costs of being a good parent. There is a cost to being attentive and caring, at least by 21st-century standards. The “hobby farm” is the first thing to suffer.

The other externality is age. I simply do not have the shoulders to swing the scythe like I used to (specifically, my left shoulder, which has decided to become high maintenance). I figure that, if I had followed the nominal biological clock and had kids at 18, at 38 I’d have several adult children who would now be homesteading. I’d be in the management role, rather than still doing the bulk of the work.

There are further externalities to the inorganic methods I’m deploying to solve the other issues. Amitraz, which I’ve used on the bees to fight varroa mites, has been found to persist in beeswax. I have no idea how amitraz and other chemicals I’m using persist, and they’re likely taking some invisible toll on the environment and our family. The brush cutter that shoots microplastics everywhere is incredibly noisy and burns fossil fuels. And my popsicle-impersonating child is siphoning energy off the grid, though I can’t complain because I love air conditioning now as well.

Part of me recognizes that this piece is a list of excuses and rationalizations for what a future version of myself, or my children, might consider crimes against the planet. Or against myself. These are the compromises I’ve made to pursue a thriving homestead given my limited time and energy. They may not be the right compromises, but for now they are staving off that pervasive, inevitable green.

Will, the marvels of modern chemistry can be an eye opener. However, I think your worries about degrading the global climate are too general. Think local.

If there are rivers near you, permethrin runoff from those thunderstorms will kill the fish. And maybe you should have a warning sign for any visitors who arrive with cats (deadly for those pets). Inorganic pesticides have also been identified as culprits in colony collapse disorder, thus the increased mortality of bees you noted.

“…levels everything intentional about the landscape” — well what exactly is your intention? If you’ve got that much “wild” around you, consider a different plan to combine joy of nature with safety of home. Perhaps let that “back forty” expand and devote less effort and less poison to a smaller area that encircles your home?

Hi Martin, thanks for writing! You’re absolutely right about the risks of pyrethrin and permethrin. A few years ago I tried to pitch an article to various hunting magazines criticizing “Thermacell” products used by sportsmen to repel mosquitoes out in the deep woods. Essentially nebulizes permethrin into a cloud. Nobody wanted the article. Maybe too many advertising dollars involved.

It’s funny you bring up housecats. Because white-footed mice are the major reservoir of Lyme disease in my area, one idea I had to mitigate the tick problem was to get a few barn cats to prowl the property. But as you know, housecats kill something like a billion songbirds every year in the USA alone. We love our bluebirds and orioles.

The struggle is real. Suffice to say, I have not found a graceful solution to the problem. Hopefully someone smarter than me can.

Thank you for writing. A very informative and entertaining read. I don’t see why you should torture yourself for using reasonable tools. Nothing inherently ungodly or immoral about a chainsaw that I can tell…

“In 2022 I had both COVID-19 and Lyme disease”

Both diseases are the product of government research labs, not “natural”, it should be pointed out…

Hey Brian, thanks for reading! I appreciate the words. As you can see, I’m still self flagellating.

I did see that a team had worked on the Lyme origin story and believes it is about 60,000 years old: https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/ancient-history-of-lyme-disease-in-north-america-revealed-with-bacterial-genomes/#:~:text=A%20team%20of%20researchers%20led,before%20the%20arrival%20of%20humans. Who knows, all I know is that it annoys me, big time. As if we didn’t have enough to worry about, Powassan virus is apparently out there in my state too. 12% of people who contract it straight up die and there is no treatment.

And there’s huge piles of papers claiming COVID totally came from nature and not from a lab, too.

All we can do is stumble our way along and try to figure things out as best we can.

I agree about the chainsaw. Pretty low tech and minimal pollution. If my trees needed to be thinned more than once a year, I might buy one, too.

I’m teetering on the edge of bee keeping, and planned on trying Warre hives. Do you have any experience with them? The glossy brochures (19th century books, but…) say that the Langstroth hives unnaturally stress bees to increase honey protection, and that Warre hives allow bees to keep the varoa mites etc. in check.

My “hobby farm” is a largish back yard, so you’re free to consider me a dilettante.

Keep doing your thing.

Hi Matthew, I encourage everyone to at least try beekeeping. There is nothing else in the world like sticking your hands into thousands of insects. Langstroth called it the “poetry” of the rural economy for a reason.

If you want to dip your toe in without committing, take a look at your county or regional beekeeping org and see if someone will take you under a wing (or four)

I don’t have any experience with Warre hives but, just from what I know about varroa’s life cycle, I am not sure the claims ring true. I have read that feral bees (that is, escaped swarms) are largely extinct from Europe after the introduction of the varroa mite the 80’s (here’s discussion of that: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34940215/). Feral bees construct hives in the most natural way possible, to their liking, and still get annihilated by varroa.

Best of luck!

As someone who is from the city that moved to the country and stayed for 14 years living the homesteading life, I’m hear you. I have to say, though, the way you describe your life on your land, it sure does sound like you are at war with it. What do you suppose farming folks did 100 years ago before the advent of industrial agricultural equipment and chemicals?

There’s a good point there: our tinkering has created a lot of these newer problems, and now we have to tinker even more to solve them, or at least resist their effects.

As some bard or other once put it, “History shows again and again how nature points out the folly of man….” Very true, but try getting the “tech solutionism” genie back in the bottle.

I definitely agree with both of your points. To some extent, I can’t escape the decisions made by people hundreds of years ago that influence how I do homesteading today. Can’t get too stressed about decisions made before me, all I can do is react.

Chris, point taken on what people did 100 to 1000 years ago. I suppose I’d argue a few things: first, as I said in the article, that at 38, I’d have a couple of kids doing work for me (and die in my 60’s); second, that I’d likely be on the edge of starvation most of the time; third, that two hundred years ago in America a lot of agriculture was performed by chattel slaves; and finally that farmers from earlier eras had their own chemical warfare. On that last point, for instance, the entire process of producing lime to amend the soil is so toxic and dangerous for everyone involved that you wonder how anyone survived farming here in PA with our acidic soil.

There’s a one of a kind show called “Victorian Farm” produced by BBC that shows the realities of homesteading during that era in Britain and boy do you get a feel for how people had to struggle to survive.

You’re getting a little vague here, Will. How much is “a lot” of agriculture depending on slaves? Most of the economic value of large scale slavery was for cash crops like cotton, not homesteads.

And be careful about life expectancy stats, such as “I’d be dead at 60”. Infant mortality was way higher in past eras. So get out your calculator and average 1 death at age 0 with 9 at age 70.

Reading this gave me pause. I felt the scale of your venture, your desires in beekeeping/general farming, and the many natural beings that co-occupy the space with you, native and otherwise.

Could it be possible that agrarian life is really only meant for certain places, climates? That perhaps your plot, your space, seeks to be unyieldingly ‘wild’ and so you might forever be in opposition to it? Or is it perhaps an issue of scale? I remain curious…

To partner with the land is to be free, I feel. This reads like a human seeking to fit their ideals onto a place that would seek to live otherwise, a place that was likely only meant for limited seasonal foraging, as opposed to agrarian capture and pasture. A place filled with ‘dangerous’ (to humans) beings yet a place that sounds wonderfully beautiful and wild. A place to be careful with, to listen to, and honestly, a place that might need to be left alone to find its own rhythm despite the human desire to occupy.

I do not dismiss the human touch, introduction of foreign species of both flora and fauna. I do wonder if there is a way to commune with them, partner with them, even (for want of a better term and practice) leverage them to your advantage?

My query for you is: is it worth it? This approach, this place? Does this venture fill your life with grounded purpose and meaning or is it perhaps time to surrender and consider what a life, a place, that is more in flow with your current needs might feel like?

I have spoken with those that track (and harvest from) wild bee colonies who have said they are vastly more resilient than the domestics. This harvest is sporadic and not guaranteed, of course.

I wonder what your wild self would say, to this unyielding green, if you could listen to its voice? I also wonder what it might share.

Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

If someone could come up with an effective organic or mechanical control of stilt grass and multiflora, they’d be a millionaire. I don’t think people recognize how invasive these plants are. To give an example, there used to be a ~3/4 of an acre raspberry patch that I’d forage every year. One year, I happened to notice a few M. rosa taking hold. By the following year, they had completely overrun the entire area. People joke that you can’t kill raspberries. Well, you can. You just have to plant multiflora. I’ve read that one plant can produce up to a million seeds (though not all are viable). Being a rose, there’s also those damn rhizomes. You really can’t win.

I really wish there was an answer. It’s like diet – yeah, on paper it looks like veganism would solve all the world’s ills, but where does the fertilizer come from? What fuels the tractors? Is that really the best use of the land? Is that really the best human diet? Digging into these topics intellectually is one thing, but once you get your hoe in the ground, you inadvertently wind up exposing a massive seed bank of externalities. There’s really no telling what’s going to sprout.

(Re: stilt grass. Get it now before it goes to seed. That can help somewhat and it pulls out easily enough. FWIW, it makes a pretty good insulator. I’ve used it to pack hay boxes. Just don’t use it as a mulch…I am not a smart man.)

Superb honesty. This is a case study for encouraging people to stay on smaller pieces of land, particularly people with families. As long as there is a water supply, there is an almost unlimited amount a family can do on an acre or less and not feel the burdens of maintaining larger parcels. Partnering with an acre or half an acre is still a partnership.

I agree with Kyle, and if you want to see the Green Knight defeated watch sequential grazing by goats, cattle, sheep. I operate a Goat Dairy with 60 does producing 120,000lbs of milk annually or 12,000lbs hard cheese and our total pasture is 18acres. I cannot imagine trying to manage 40 acres as a hobby. Personally I keep our home place maintained below 1/2 acre and feel I want nothing more. I could easily raise the majority of my family’s vegetables on our ground, but larger plots are for commerce or livestock.

I believe hyper efficient houses and cooperation are much to be desired. One person cannot effectively raise a multitude of crops/insects/animals and actually get performance per square foot. I think one person doing bees, one doing goats, one doing sheep etc working in cooperation is what is hopeful, otherwise you live out jack of all trades master of none. Efficiency and yield per square foot come from mastery not hopefulness.

Love where your heart is Will, I just hope you can find peace and good balance with it.

Comments are closed.