Like dew on the gowan lying

Is the fa’ o’ her fairy feet;

Like winds in summer sighing,

Her voice is low and sweet.

Her voice is low and sweet,

And she’s a’ the world to me,

And for bonnie Annie Laurie

I would lay me doon an’ dee.

From the old Scottish ballad, Annie Laurie

What a girl wants, what a girl needs

Somebody sensitive, crazy, sexy, cool like you

What a girl wants, what a girl needs oh ohohoh yeah

Whatcha got is what I want

What a girl wants, what a girl needs

It’s so right, it’s so wrong

Ya let a girl know how much ya care about her, I swear

You’re the one who always knew

Oh ya knew, ya knew, ya knew

From a hit “song” on the planet Obsessus

Rummaging about in an old book store this summer, I found a copy of a Community Song Book, printed in Canada and falling apart, apparently from long and constant use. The book was filled with genuine folk songs, that is, songs beloved by the people and passed down from one generation to the next, because they were beloved. There was quite a broad range, too, in this little book. There were anthems, and since this was Canada, that meant not only O Canada, its lyrics unexpurgated by the thought police, but also the boisterous Rule, Britannia and The Marseillaise. There were sweet love songs, like Annie Laurie and Loch Lomond and Juanita. There were gently mournful songs of sorrow and loss; silly playful songs; songs from the American south, from Hawaii (Aloha, Oe), from all over Europe.

Some of the lyrics were written by poets of the first rank: Ben Jonson’s Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes; Robert Burns’ Auld Lang Syne. Others were written by some unknown poet, or were like sudden springs bubbling up out of the common heritage of music. The melodies covered the same range, from the haunting minor key melodies of the negro spiritual, to military fanfares, to the simple bumptiousness of comic songs (Old Dan Tucker). Dvorak and Schubert find a place beside Stephen Foster and that busy fellow, Composer Unknown.

The foreword to the book says that there is nothing so vital for bringing a community together as is song – community singing. That is why the music is scored for four-part harmony, so that really experienced community singers could venture forth into the fine complexities of soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. The people, then, would experience the music not only by hearing, but by singing, and not in unison, but in union. “Various voices make the sweeter song,” says Dante, explaining the differences in rank among the blessed souls in heaven; and so too, in the choirs that used this book, young and old would find their harmonies, boys and women and men, and all classes of people. That explains, too, the prominence of the most important kind of song in the book, the hymns: Nearer, My God, to Thee. For people are most truly united only from above, never from below.

It’s with a shock, then, that we turn to the lyrics of the planet Obsessus, sublingual coos and grunts, without coherence, sweetness, grace, solemnity, mirth, or humor; entirely focused on the self, valuing the “you” only as a provider of commodities: what a girl wants, what a girl needs. On Obsessus, not many people play musical instruments. They don’t have community song, in part because they have no community, and in part because they have no song. They don’t actually listen to music, although they believe they do. (I owe this insight to the brilliant Ken Myers, of Mars Hill Audio, who has visited Obsessus and taken careful notes of the anticulture there.) They do not sit quietly and attend to it, as one might attend to Dvorak’s New World Symphony – which Dvorak himself could write only because he had visited America, when there was an America, and gotten to know her people, and had heard their songs. They play it as noise to accompany something else they are doing, quite often something that also bears the character of a compulsion – they are working at a job that bores them, they are “hooking up” with someone whose name they didn’t catch, they are jogging to lose those last five pounds or trim off that last inch of the commercially decried “unwanted belly fat,” or they are cramming food or facts or forms to fill out.

They are, on Obsessus, using “music,” or at least a canned array of sounds, as a means to scratch an itch. It’s as if one were to place a mechanical rake on the back of one’s chair or brain. The use of the music reflects both its subject and its form. These are extraordinary narrow. They cram those who cram, into the tight anxious space of narcissistic self-inspection – but never introspection.

Which brings us back up to earth, the planet whose night skies, unlike those on Obsessus, are open to the heavens. The man who first sang of Annie Laurie held that young lady in his mind as the epitome of beauty. He remembers himself only in relation to her; whereas on Obsessus the singer remembers the lover only in relation to the self. He can see her fair hands and her neck, he can recall her gentle voice. He is far away from her, he may never see her again, but for her, for bonnie Annie Laurie, he would lay himself down and die. He doesn’t intend that as a boast, but in that lovely final line – and its surprising full-octave leap, on the syllable lay – he rises in our esteem, precisely for his devotion and his humility.

There’s all the difference in the world between teaching a human being and sanding the gears in a machine. The machine does a job. The human being embarks on a quest. The machine hums, a dreary, constant drone. The human being sings.

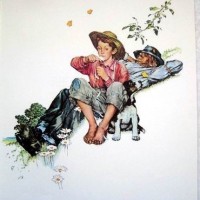

Let me give another example of humanity on earth, not machinery on Obsessus. It’s of a Catholic boys’ school on the top of a mountain. The boys live there. They all learn to sing songs – sea chanties, ballads, hymns, Gregorian chant. They all serve at the altar. They play rugby and soccer, outdoors, whenever the weather will permit, and roam over the mountain in their free time. They read good books.

They also learn to juggle. One of their teachers caught the idea, and after a few years, the boys became wondrously nimble and clever at it, inventing all kinds of things to juggle, riding unicycles, singing, tossing bowling pins or torches or baseballs or knives, and passing their know-how along to the younger boys, just as they’d done on the playing fields and at Mass.

One summer, five or six of the high school seniors flew with their teacher to Barcelona. They brought their juggling equipment, their bicycles, their camaraderie, their songs, and their faith. What they did not bring was money. They then proceeded to travel on a pilgrimage, a quest, from Barcelona to the shrine of Saint James in Compostela, hundreds of miles away, across the foothills of the Pyrenees. How did they eat? What did they drink? Where could they lodge? They sang and juggled for their food and their rooms.

Place the planets side by side. Here is Obsessus. It’s a train car. A pinched young person sits next to another pinched person, but nobody speaks. He has a plug in his ear, listening to the scratch. He is staring at a hand-held computer. His knee twitches, annoying the person beside him.

Here is earth. Here are the boys on their bicycles, chatting and laughing. They have to stand up to pedal, because the Pyrenees are steep and mighty. The Spanish sky stretches out above them. Their friendship is rooted not only in what they sing, but the God to whom and for whom they sing. They have all come from the same small school in Pennsylvania, but they are all going on a quest to the ancient Galician church, where millions of pilgrims have gone before, but not as anonymous millions – rather as human beings, penitent, joyful, grateful, sorrowful, young and old, men and women, the brave and the timid, the healthy and the dying. They are themselves a real community, and are a part of a community that stretches back for hundreds of years.

Their songs are as open and clear as that sky. All their songs, whether sea-chanties or ballads or hymns, are songs of love, and breathe the fresh air of the quest. How weary, stale, and flat, by contrast, are what passes for love songs on Obsessus.

15 comments

James Kabala

“He remembers himself only in relation to her; whereas on Obsessus the singer remembers the lover only in relation to the self.”

That’s an interesting distinction I would like to see explored further. I believe Michael Jackson actually had a song that was outright called “The Way You Make Me Feel.” On the other hand, though, it seems to me that in many works both old and new the distinction can become rather ambiguous or blurry.

Chris Travers

@Jon S:

Music isn’t meant to be *read* but *listened to* and then *sung.* 😉

Jon S.

I find it ironic that folks are suggesting recorded music. I would think the proper thing to suggest is a good song book. I am one of Prof. Esolen’s uneducated blobs, i.e., I don’t play an instrument. But my wife plays piano and I can sing and we use the following song book for folk music: http://www.amazon.com/The-Great-Family-Songbook-International/dp/1579128602/ref=rec_dp_3

Chris Travers

@Jennifer

Germany between the Treaty of Versaille and the end of WWII is sufficiently unbalanced and weird that I don’t think one can draw many conclusions as to what things would look like in a more ballanced society.

However, even if we do go there, it can’t be an accident that the NSDAP aligned itself both with the so-called Pan-Aryanist movement[1] and against the Volkische movement,[2] despite Hitler in particular not being a part of either movement.[3] It is worth noting that prominent Volkische leaders were thrown in concentration camps or simply disappeared under Himmler’s orders.

[1] This movement saw the ancient Germanic peoples as the vehicles of language and culture worldwide. From this viewpoint the Vedic Aryans must have been Germans because they brought Sanscrit to India, and other groups, such as the Jews, were basically cultural thieves….

[2] This movement saw the way forward for Germany and other places as being with a localist neopagan approach, focusing on Germanic heritage (possibly including some comparisons) but expecting other groups to research their own heritage too. I am not aware of many early Volkische groups that were more hostile towards Jews than average Germans were (though this is setting the bar low) and some of the early voices were actually quite collaborative with Jewish Kabbalistic movements as well (Guido von List not only had a Rabbi on the initial board of directors of the Guido von List Gesselschaft, but was apparently working on a book on Jewish mysticism co-authored with this Rabbi, which to my knowledge was never published).

[3] In his letters to Himmler, Hitler portrayed himself as a sort of mystical modernist who worshipped science and felt that Christianity outmoded all this Wodan worship, but also that science was killing Christianity.

briana

Now that I think about it, I am wrong. 🙂

briana

To Andrew: I thought that scene was in Dark Shadows. Unless, of course, I am wrong…

andrew

How is it smug to prefer, say, “Craigie Hill” over “I wanna sex you up”? Besides, even if Jennifer were right about Prof. Esolen, one can be smug and still be right.

It’s begun to dawn on me that those who claim they don’t see the aesthetic difference between such things, who insist on chacun son gout, are simply lying through their teeth and they know it. There is a scene in the vulgar movie “The Campaign” in which two foul-mouthed parents who are about to hurl profanities at each other in front of their kids politely ask the kids to put on headphones and listen to music. The kids obey and are then shown listening to a rap song whose lyrics consist of nothing but “ass and titties, ass and titties….” The scene is only funny because it’s true.

Goodness knows I too feel the pang of a lost world.

Tony Esolen

Jennifer: Abusus non tollit usum. Hitler also built the Autobahn. We should tear it up, therefore? The question is not whether a thing that is good in itself can be put to evil use. All good things can be put to evil use: angels are bright still, though the brightest fell. The question concerns the nature of the music currently mass-marketed — stick to that. I am claiming that we really have a new thing in the world, and a bad thing — canned, mass-produced pseud0-music that is meant for consumption, and that is inextricable not from bawdiness (very little of it is genuinely bawdy, because very little of it gives evidence of mirth) but from prurience. When I look at something like the community songbook, I feel the pang of a lost world. That’s not smugness. It is sadness.

Briana

Question to Reader: what do the articles you posted have to do with folk music?

Jennifer Krieger

Weren’t there also enthusiastic, fresh-faced, Hitler Youth marching and singing folk songs not so long ago? I myself prefer most “folk” music to contemporary music, but you come across as insufferably smug.

Chris Travers

For those interested in the deep trad folk scene, here are some artists I highly recommend:

* Dick Gaughan, particularly his “Kist o’Gold” album, Scottish ranges from trad to modern.

* Kate Rusby (I am a big fan of Hourglass, as that is probably her most clearly trad album, but the rest is really good too), trad to modernish trad, many of her own songs sound more trad than modern. English (Yorkshire).

* Archie Fisher, mostly trad, even his own compositions sound more trad than modern. Scottish.

Resources for study include, of course, the Child Ballads, the Percy manuscript, and a bunch of other sources.

Reader

Here’s a recent article by Ron Unz, “How Social Darwinism Made Modern China,”

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/how-social-darwinism-made-modern-china-248/

that everyone is going to be talking about.

It seems to make similar claims as a recent article by Geoffrey Miller, “Chinese Eugenics”:

http://www.edge.org/response-detail/23838

…

Briana

For anyone who is interested in folk music, especially Celtic folk music, I’d recommend the Scottish singer John McDermott. He sang a beautiful rendition of “When Irish Eyes are Smiling” at one of the memorial services for Senator Ted Kennedy, and while I can’t say anything about Senator Kennedy, I can say that Mr. McDermott has a wonderful singing voice and does great interpretations of old folk songs. And this is coming from someone who is 23 years old. 🙂

Nicole

Mr. Esolen: Thank you for writing this series. You have laid forth so well the reasons to engage in the work of educating a whole person. Half my family thinks I’m crazy to take on my children’s schooling at home, but as I read through your posts I am strengthened by the knowledge that this is a better path for our family.

Chris Travers

it’s interesting. This is a topic I have thought a lot about.recently. The fact is that the old folk songs often have a level of sex and violence that is altogether not represented in modern popular music.

For example, consider:

“CHILDE Watters in his stable stoode,

And stroaket his milke-white steede;

To him came a ffaire young ladye

As ere did weare womans weede,

Saies, Christ you saue, good Chyld Waters!

Sayes, Christ you saue and see!

My girdle of gold, which was too longe,

Is now to short ffor mee.

‘And all is with one chyld of yours,

I ffeele sturre att my side;

My gowne of greene, it is to strayght;

Before it was to wide.’

The balled goes on and he mistreats her including demanding that she goes down as his servant and hires him a prostitute. The ballad ends with her giving birth and him agreeing to marry her on the day of her churching.

Then you have Tam Lin where premarital sex with an apparent elf results in pregnancy which when it is discovered leads to an attempted abortion (unsuccessful) and finally an attempt to help the “elf” who is now revealed as a kidnapped human to escape back to the world of men before he is to be the victim of human sacrifice.

Themes of filicide, fratricide, and the like are common in the older ballads as is incest, premartial sex, and even human sacrifice (I have argued that throwing the Captain’s wife off the boat in Banks of Green Willow is essentially a human sacrifice, and a similar theme is present in William Glenn at least as sung by Nick Jones).

At the same time what is missing is the level of narcissism found in current popular music. If you put these themes aside the popular music of today, they are deep and real in a way that makes the popular music seem shallow and self-centered.

Comments are closed.