[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

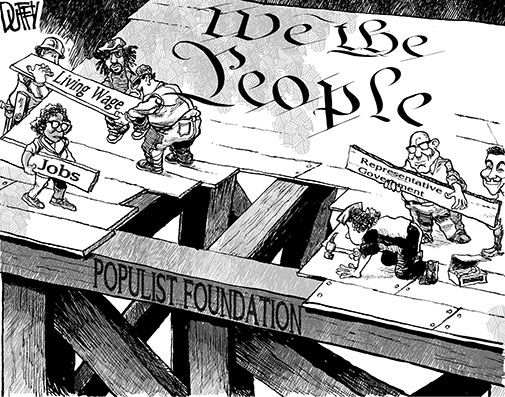

The departure of Donald Trump from the White House [crosses fingers] will assuredly not mean the departure of Trumpism from American life. The collection of grifters, paranoiacs, and devout (and, I think, devoutly misinformed) Christians who embraced Trump as the salvation of our broken liberal capitalist state may or may not stick with the man himself (or rather with the narcissistic tweetstorms that will no doubt continuously flow from his mansion in Florida), but the populist discontent which he channeled, the sense of technological alienation, socio-economic frustration, and constitutional disregard many justifiably feel in relation to our ever-increasingly unequal, undemocratic, and elite-driven country–that, I’m certain, we’re stuck with. That can be seen as a threat requiring constant condemnation–or maybe, instead, we can dig into this discontent, find its constructive elements, relocate them, and use them to build a different, more local and less easily abused political foundation.

Of course, figuring out how to disentangle Trump from ideas embraced by, at the very least, hundreds of thousands of voters, is no simple matter. Populism–which, borrowing from The Oxford Handbook of Populism, I’ll define minimally as “an ideology that posits a struggle between the will of the common people and a conspiring elite,” and thus is, among other things, “a normative response to perceived crises of democratic legitimacy”–is an alluring idol, the promise (one which many consider democratically dangerous) of making political connections with the imagined masses who feel alienated from or resentful towards those who wield social power within the dysfunctional mass democracies of today. I say “imagined” masses not because I reject the possibility of such alienation and resentment operating on a nation-wide scale; rather, I call it imagined because the populist articulations we see around us, whether expressed as a positive or a negative, are almost inevitably couched in a statist, collective context–and the pioneering work of Benedict Anderson decades ago has made it impossible, I think, for serious people to speak casually of national communities and their political expressions through states without recognizing their fundamentally “imaginary” quality, as things constructed through acts of affective identification and imagination.

Scholars who recognize this imaginary element in the politics of the contemporary democratic nation-state are often quick to suggest alternative stories which the inhabitants of such states could, or should, tell themselves, so as to short-circuit the lure of populist stories that, in the view of many of them, invariably cast the fight between the “common people” and the “conspiring elite” in dangerously ethnic or exclusionary terms. Their goal is to find a way to cast the affective identification and imagination at work in liberal capitalist states into the civic realm: hence, “civic nationalism” or “constitutional patriontism.” This effort, while it has had great influence in the scholarship on national identity over the past 30 years, has seemed less than wholly convincing as populist narratives have revived over the same period. Rogers Smith, while sharing the fear of these scholars regarding the threat to liberal democracy which populist narratives present, suggests that any political story which fundamentally rests on “pledging allegiance to an abstract creed” is doomed to struggle.

Instead, Smith argues that those stories which will lastingly engage the affective imagination of a people are the ones which focus on “a shared endeavor that participants can see as expressive of their identities and interests as well as their ideas.” This is not a denial of the constitutive role which acts of political imagination will invariably involve, but it suggests that such affective expressions need not be either “mechanistic” (which suggest unchanging laws or identities) or “teleological organicist” (which suggest an inevitable evolution towards a destiny or end-state); a people can also see itself constituted through “contextual accounts” which derive from mapping “how the interactions of different units in [society] foster change in those units and in the society as a whole.”

Given Smith’s appreciation of the constitutive function which a story about the contextual interactions of different aspects of a social group can serve–an appreciation he deepens even further when he associates the best kind of national stories with “reticulation”: that is, they will “weave networks” that “transform jumbles of differences into more orderly and attractive arrangements that generally have more utility and durability”–it is unfortunate that he never seriously considers any group besides the nation state. After all, his talk of contextual accounts of a jumble of different subgroups and distinct social units being woven into a network which constitutes an appreciation of the whole has an obvious analog in a very important, though clearly not national, form of imagined community: the city. Consider the applicability of Smith’s considerations to Jane Jacob’s justly famous description of the “sidewalk ballet” of a thriving city in The Death and Life of Great American Cities:

Under the seeming disorder of the old city, wherever the old city is working successfully, is a marvelous order for maintaining the safety of the streets and the freedom of the city. It is a complex order. Its essence is intricacy of sidewalk use, bringing with it a constant succession of eyes. This order is all composed of movement and change, and although it is life, not art, we may fancifully call it the art form of the city and liken it to the dance–not to a simple-minded precision dance with everyone kicking up at the same time, twirling in unison and bowing off en masse, but to an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole. The ballet of the good city sidewalk never repeats itself from place to place, and in any one place is always replete with new improvisations.

That Smith does not recognize this obvious parallel is perhaps a matter of convenience; while he allows that our globalized and interconnected world allows for a cacophony of potential political stories, he sees “narratives of nation-states” as possessing a “simplicity, clarity, and authority” which “proponents of rival senses of political identity often can manage only with great difficulty.” Or it is possible that he sees that convenience as reflecting something natural and inevitable. William Galston, relying in part on the political theorist Pierre Manent, makes this point multiple times in his own recent attack on populist narratives; it is essential, he writes, to make a civic case for the pluralist and democratic nation-state, because only a government that is incorporated by national bodies can have the scale of representation to make genuinely “legitimate decisions about laws and rules,” and only a national body can incorporate enough resources to generate the sort of wealth that can reward the very human characteristic of “ceaseless effort and ingenuity in the service of material improvement.” Democracy at our present moment, according to this argument, requires a liberal capitalist nation-state, and since such states create elites, and elites can be depicted as threatening the common people by populist demagogues, the great task of theorists of democracy, in Galston’s and Smith’s minds at least, is to call for the sorts of stories and public policies that will prevent the populist narratives which are parasitic upon such states from gaining any political ground.

My concern, at this point, should be obvious: if the fundamental problem with populism–and the efforts which some theorists go to either counter or re-orient its appeal as a constitutive narrative of affective imagination–is the complicated fact of its appeal to the feelings of powerlessness and longings for popular control which exist in the contemporary nation-state, then what about focusing on the constitutive, people-building power of other, less statist scales of belonging? Of course, so long as our national governing bodies wield sovereign power, and our major media organs remain committed to casting every debate into terms of what effect said debate will have on the use or abuse of state power, any such alternative will face many practical obstacles. But those obstacles may not be insurmountable.

One particular way in which localism has taken on theoretical forms which potentially carry with them real possibilities for constituting a sense of popular identity is the family of ideas which are sometimes referred to as the “new municipalism” or “radical municipalism.” Heavily indebted to the “libertarian municipalism” of Murray Bookchin, but expressed in light of a more locally interconnected understanding of participatory democracy than his did, it is an attempt to think more seriously about what a politically empowered egalitarian commons would look like in a localized urban context. That such models can be productively imagined and politically built upon in relatively rural contexts is an understanding as old as Thomas Jefferson’s proposed ward system or Alexis de Tocqueville’s idealization of the egalitarian town meetings of 19th-century America. The parallels between those associational forms and those spoken of by the Populists of late 19th-century America are strong–but considering how poorly the Populists fared in America’s urban centers, that would only seem to further suggest the incompatibility between populist formations and the urban life most American citizens live.

Yet perhaps the distinguishing feature that municipalist narratives could offer, one which borders on the populist articulation of a defense of the common people and yet does not get hung up on inevitably statist definitions of citizenship and claims to a sovereign people–definitions which, in the 19th century, became entangled with an anti-urbanism and an anti-immigrant ethnic sentiment, echoes of which continue to Trump’s so-called “populism” today–is their rigorous focus on the most basic phenomenological fact of urban life: bodies in proximity to each other (which is exactly the same central reality to Jacob’s sidewalk ballet). As Bertie Russell observed:

[The] municipalist movements have found themselves building on a unique potential of the urban–proximity. In its simplest forms, we can understand the quality of proximity being the observation that…the local level is the place and a space where shifts and changes can truly be transformative in terms of impacting people’s lives….[Their] initiatives are harnessing the potential of the urban scale through adopting a politics of proximity, the concrete bringing together of bodies (rather than of citizens, who already come with a [state-defined] territory) in the activation of municipalist political processes that have the capacity to produce new political subjectivities….[We] should understand the politics of proximity as attending to those forces that pull us together, as opposed to those forces that push us apart. Whilst contemporary urbanization is characterized by the ever-increasing massification of bodies…this same urbanization is driven by dynamics that pull us ever further apart. Perhaps it is precisely because of this contradiction that the municipality has been adopted as a key site through which a politics of proximity can be pursued.

While the theoreticians of municipalism have thus far, to my knowledge, not thought to connect populist stories about constitutive identification (or their more civic equivalents) with the urban “subjectivities” that they see as emerging through the politicalization of the proximate bringing together and shifting and changing of human bodies, the parallels are, I think, obvious. The focus on the needs of human bodies, on organizing to maintain their proximate patterns of movement and change, or resisting those socio-economic forces which pull people apart, inducing alienation in the place of togetherness–that all can fit within a populist framework. Remember that Smith argued that the best stories of identification must incorporate some degree of “reticulation,” some respect for the pluralistic “patterns among the elements that constitute a larger whole.” In rural or suburban environments, it may correctly be the fact that the distance between bodies requires a narrative of affective and imaginary identification on a national scale, since locally there isn’t sufficient shifting and changing to prevent the craving for such stories to land upon exclusive, ethnic ones. But in cities? The requisite reticulation which the constituting story needs to making human plurality into a part of one’s imagined community, rather than an obstacle to it, will be as obvious as the foot traffic on the sidewalk outside one’s front door (or at least potentially could be, anyway).

Margaret Kohn’s work on the “urban commonwealth” provides a specific example of putting this kind of imagined subjectivity–a non-statist, urban sense of the common people united against those who would alienate and privatize them from one another–to direct political work. Kohn refers to the theoretical construct she explores as “solidarism,” but at one point in her analysis the populist parallel is made explicit. Using the urban uprisings of a decade ago–Occupy Wall Street being the best known in the United States, but with parallels all around the world–as her model, she suggests that life in cities today is increasingly teaching more and more people to rethink how they see themselves as bodies which occupy public, democratically articulated spaces. In association with that particular urban education, Kohn postulates a greater awareness of how it is that those spaces, and the means by which they are “common” to those who live and move and change within them–speaking here of the roads and parks and playgrounds and markets through which healthy urban activity is expressed–are separated from them, thus making them, presumably, something that people can feel no politically identifying affection for.

Enabling this awareness are the operations of, in Kohn’s words, “two very different understandings of the term ‘public.'” The first she calls the “sovereigntist model, which identifies the public with the state,” and the second the “populist model, which sees the public as a force which emerges outside of state institutions in order to challenge policies and publicize issues that do not make it onto the government’s agenda.” Predictably, the sovereigntist model requires a regulative state in order for the urbanites to find identification through their actions in their spaces: “A public space is one that is owned, authorized, or regulated by the state.” Whereas the populist model defends the contentious interaction of persons, with their always shifting associations, as a necessary component of persuasion; it justifies “the public as a force that emerges outside of state institutions in order to challenge policies and publicize issues that do not make it onto the government’s agenda.” In short, Kohn is pointing to a kind of populist imaginary which comes from the same space as the subjectivities which radical municipalism invokes: finding oneself constituted as a community through the practice of “extralegal” action, putting bodies into public space “as a way of ensuring that the law does not protect the interests of the elite at the expense of the common people.”

Obviously, talk of the people being able to exercise political force in regards to public places “outside of state institutions” is terrifying to those who consider state-enforced property rights to be sacrosanct. Such urban and local populist formulations do not necessarily take a clear position on the place of private property (Kohn herself doesn’t, recognizing that the idea of “social rights” or the “right to the city” are far from fully developed), but again, the key point is not contesting every particular argument being made as part of this intellectual shift. Rather, the point is taking up the discontent which issues in the whole drive to politically express oneself through one’s collectively self-articulated people and place, and explore the possibilities of the shift itself.

It is my belief–and, with a little creative re-interpretation, perhaps a belief which aligns with the theoretical work done by the theorists and activists mentioned here–that populism, the popular engagement of people against elites, can be made relevant to political formulations outside of national imaginaries. And if the rhetoric of populism really can be theoretically articulated as a local and urban matter, then perhaps exclusive national narratives, whatever their effectiveness, could also be understood as invoking a language which is parasitic upon the embodied place where populist feeling mostly actually resides. To be certain, it is ridiculously unlikely that a conceptual exploration like this one could be persuasive enough to be even just a small part of making incoherent any further Trumpist and state-dependent abuse of the valid populist sentiments out there. But given how likely it is that our national pre-occupations will allow bad actors like our soon-to-be-former president to continue to turn legitimate frustrations with the elite disregard of our proximate (and, for most of us, urban) places in nationalist, exclusivist directions, any rhetorical and intellectual resistance, however small, is worth doing.

3 comments

Martin

Russell, Thanks for a thorough and cordial reply.

Regarding this part:

*Whatever the weaknesses of this little essay, I actually think that I may be on to something here: namely, that the root (or at least one of the roots) of the populist sentiment really can be plausibly connected to the proximate practices and shared spaces of urban patterns of life, as opposed to the invariably statist national or ethnic categories (“real Americans,” etc.) which so often shaped populist discourse in the past, and by so doing allow this ideological construct to escape some of its own (justifiably worrisome) exclusionary history, and become more relevant to more localizable democratic projects.*

I do think you’re onto something and I now realize that some of the lacuna (and occasional sloppy editing) of your recent essays are due to your shortening your original arguments.

As for AOC, let’s leave aside her embarrassing confrontation with a kitchen waste disposal unit, which does appear in horror movies and was probably banned in NYC before she was born. Her claim of being descended from Spanish Jews (“it sounds plausible, therefore it’s true” mode of thinking) is airhead-ish, revealing a serious lack of appreciation for history and rather general currents within it.

Debunked here:

https://www.jpost.com/Opinion/Challenging-Ocasio-Cortezs-Sephardi-claims-575146

Russell+Arben+Fox

Thanks for the thoughtful comments and questions, Martin! Some responses:

How exactly is this essay about a pandemic? The word doesn’t appear after the title. And the issues date back millennia to the earliest cities on this planet.

Honestly, it isn’t, and I should have taken that out of the title. You can probably find seams in the essay where I took stuff out and tried to stitch up what remained to blog post-length; the original paper (which itself is a version of something that will get much further work in the weeks to come) did have some explicit references to how “populism,” as an ideological construct, has played out in arguably contradictory ways during the pandemic (for example: if the so-called “populist response” can be understood is people attempting to protect their places and ways of life in the face of elite–and sometimes foreign–condescension/intervention, then isn’t it inconsistent that anti-mask responses to the pandemic have also been coded as “populist,” since that is fundamentally a protectionist act?) But in any case, you’re correct; the things that I’m talking about are in no way specific to urban conditions which have emerged during the Year of Covid, but rather are reflective of political articulations that are as old as cities themselves.

Similarly, the dance of the sidewalk, or the way motor vehicles move through an intersection that has no traffic light or stop sign, works best when the participants know each other’s cultural habits and unspoken patterns of movement…So one of the easiest ways to reduce the risk is to impose a traffic rule.

I agree, and I don’t think I wrote anything in the piece which would suggest disagreement (though maybe I wasn’t very clear on some points). Local knowledge is central to retrieving what is most defensible and democratically important about the populist formulation, but local knowledge expressed through the means of commonly understood and accepted rules and laws doesn’t weaken local knowledge at all, I think.

When and how did “populist” become a dirty word?

Well, that’s a long discussion–and, again, parts of that discussion which were part of the original (and ongoing) paper project were cut out, perhaps wrongly. In any case, it seems to me pretty plain to me that both American-style conservatives and American-style liberals (but mostly the latter) have condemned various populist tropes with greater or lesser degrees of sophistication for many decades; Thomas Frank’s recent (and very good) book The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism provides a solid history of the many ways people of very different political persuasions have nonetheless agreed that the popular articulation of economically and politically empowering and protective demands is a terrible threat that must be roundly condemned wherever it appears.

Have you forgotten (along with most academics and journalists) that Obama was labeled a populist when he competed for the nomination in 2008?…It’s hard to follow your rambling attempt to rehabilitate the label by spinning it in a different direction for liberals who don’t remember the early part of the 21st century.

Nope, haven’t forgotten; indeed, to my embarrassment, I probably contributed, in my own tiny way, to that mostly (probably not entirely, but definitely mostly) incorrect labeling. As for the rambling quality of the post, I plead guilty. I would push back on your claim that I’m “spinning” populist constructs here, which to be implies a groundless act of rhetorical legerdemain. Whatever the weaknesses of this little essay, I actually think that I may be on to something here: namely, that the root (or at least one of the roots) of the populist sentiment really can be plausibly connected to the proximate practices and shared spaces of urban patterns of life, as opposed to the invariably statist national or ethnic categories (“real Americans,” etc.) which so often shaped populist discourse in the past, and by so doing allow this ideological construct to escape some of its own (justifiably worrisome) exclusionary history, and become more relevant to more localizable democratic projects.

IMO, airheads like AOC belong in Congress because the House of Representatives was specifically created to accommodate…populists.

I don’t personally see anything remotely airheadish about Representative Ocasio-Cortez, but you’re certainly correct that, should one embrace the original imaginings of how our constitutional system would work, then those who push populist concerns belong in the House. Interesting that historically the 19th-century People’s Party, the original American populists, did equally well at getting their candidates into state governorships and U.S. Senate seats.

Smith’s assertion about “pledging allegiance to an abstract creed” seems bizarre. What else should one pledge allegiance to? Something concrete, like a royal family or a religious hierophant?

I’m not sure how to respond to this, because I can’t tell if you’re criticizing Smith for believing in the possibility of what I called (drawing on a lot of scholarly writing on the topic) “constitutional patriotism” or “civic nationalism,” or if you’re criticizing him for imagining that there could (or should?) be anything but. For whatever it’s worth, I’m on the critical side; while I respect the work of theorists like Smith in articulating the sort of “stories of peoplehood” (that’s the title of one of this books) which they think can enable people to imagine themselves as belonging together across the polities a continent wide and centuries old, I personally am dubious that you can come up with any such “national” articulations that won’t have to fall back on ethnic or racial or religious categories, and of course on state power to draw the boundary lines between them all. So I agree that Smith’s claim that one can feel shared membership through an abstract creed is bizarre, though that may not be what you meant to say.

Do schools still teach about the French Revolution?

My college does; a whole semester-long class on it. Only comes around every three years, though.

Martin

Some questions and comments, Russell:

1. How exactly is this essay about a pandemic? The word doesn’t appear after the title. And the issues date back millennia to the earliest cities on this planet. Town halls where you can see and talk to each person are a key part of village democracy which works because everyone knows each other personally. See “Will of the People: Exploring Original Democracy in Non-Western Societies” by the late Philippine Senator Raul Manglapus.

But how can that “knowing personally” apply to human groupings of thousands or millions of people? What tends to happen in many times and places is that an individual who needs to deal with the centralized seat of power gets an introduction to one of its officials and then develops a “personal relationship” by presenting a gift (usually in advance), thus “I know that person now”.

2. Similarly, the dance of the sidewalk, or the way motor vehicles move through an intersection that has no traffic light or stop sign, works best when the participants know each other’s cultural habits and unspoken patterns of movement. Introduce foreigners (or even just out-of-towners) and the “unconscious order” becomes conscious, and possibly dangerous due to the chaos of reorganizing into a broader order. So one of the easiest ways to reduce the risk is to impose a traffic rule. Here I’m reminded of an insight mentioned in “The Mystery of Capital” by Peruvian Hernando de Soto Polar: laws work best when they follow customs, not the other way around.

3. When and how did “populist” become a dirty word? Have you forgotten (along with most academics and journalists) that Obama was labeled a populist when he competed for the nomination in 2008? One piece of evidence that his supporters gushed about was “small donations from thousands of common people”. It’s hard to follow your rambling attempt to rehabilitate the label by spinning it in a different direction for liberals who don’t remember the early part of the 21st century.

IMO, airheads like AOC belong in Congress because the House of Representatives was specifically created to accommodate…populists. Smith’s assertion about “pledging allegiance to an abstract creed” seems bizarre. What else should one pledge allegiance to? Something concrete, like a royal family or a religious hierophant? It’s hard nowadays to find a sound bite like Smith’s which applies strictly to the “other guy” and not at all to the “ideological team” of the person uttering it.

4. At present, the biggest obstacle to unity is the delusional meme “we’re inclusive except for…” Pretty much anyone who still uses common sense as a method for navigating this world can see through this kind of hypocrisy. Sadly, those pushing vociferously for justice are painting themselves into a corner of vengefulness (aka “canceling”). Do schools still teach about the French Revolution?

Comments are closed.