Eagle, ID. Joshua Pauling has recently argued for restoring physical practices such as writing with pen and paper in the classroom in order to counter the dehumanizing effects of technology. Through such practices, he argues, we challenge the “dichotomy between the physical and mental,” and extract ourselves from the “technological mindset” which disorients us from the real. While the practices he describes are indeed vital for renewing a more human education, are they enough to counter the all-encompassing push for disembodied education, work, and relationships? Or might grounding students in the real world require that we go beyond traditional physical practices in the liberal arts classroom to learning that more fully engages the material world and integrates body and mind?

Christopher Hall’s Common Arts Education makes the case for this kind of learning in the classroom. He argues that schools should teach the common arts, or the “the skills that provide for basic human needs through the creation of artifacts or the provision of services” (18). The common arts include agriculture, woodworking, medicine, architecture, and stonemasonry, among others. Like Matthew Crawford in Shop Class as Soul Craft, Hall highlights how our educational system has pushed out and denigrated skilled manual labor and craft. Hall’s book is a practical how-to for renewing a comprehensive range of embodied skills or “common arts” in the classroom.

Christopher Hall’s Common Arts Education makes the case for this kind of learning in the classroom. He argues that schools should teach the common arts, or the “the skills that provide for basic human needs through the creation of artifacts or the provision of services” (18). The common arts include agriculture, woodworking, medicine, architecture, and stonemasonry, among others. Like Matthew Crawford in Shop Class as Soul Craft, Hall highlights how our educational system has pushed out and denigrated skilled manual labor and craft. Hall’s book is a practical how-to for renewing a comprehensive range of embodied skills or “common arts” in the classroom.

Hall has at least three hurdles to overcome in making his argument for the return of the common arts to the daily lives of students, their families, or any of his readers. First is the challenge of efficiency. In our highly-specialized economy, it makes more sense to earn money in a particular field and then outsource labor beyond our expertise. Why take the time to learn the basics of metalworking, when one can hire a plumber who has years of experience in repairing pipes?

Hall responds to this objection on two levels. First, he demonstrates how ignorance of the common arts handicaps us in our everyday lives and cuts us off from vital knowledge about how the world around us works. Based on his twenty-five years of educating students from poor schools to prep schools, he paints a fairly grim picture of systemic ignorance—students who don’t know how to use scissors, tie a knot, light a match, read a recipe, or that food is grown in the soil. Recent shutdowns and shortages due to the spread of Covid-19 have also made clear that our highly efficient systems are also highly disruptable.

More importantly, Hall argues that we shortchange much more important goals if we make utility the only aim of our work. In practicing the common arts, humans live out a distinctly human telos of creating. The very first description of humans in the Christian tradition is that men and women are made in the image of God. As Dorothy Sayers points out in The Mind of the Maker, “The characteristic common to God and man [in the first chapters of Genesis] is … the desire and the ability to make things” (22). In practicing the common arts, humans live out our role and nature as sub-creators.

More importantly, Hall argues that we shortchange much more important goals if we make utility the only aim of our work. In practicing the common arts, humans live out a distinctly human telos of creating. The very first description of humans in the Christian tradition is that men and women are made in the image of God. As Dorothy Sayers points out in The Mind of the Maker, “The characteristic common to God and man [in the first chapters of Genesis] is … the desire and the ability to make things” (22). In practicing the common arts, humans live out our role and nature as sub-creators.

Practicing the common arts can foster our own spiritual growth as well. While one may know intellectually that patience is a spiritual good, the long and careful cultivation of a garden actually develops that virtue in a person. Unlike many ancient authors, the 12th century educator Hugh of St. Victor valued the common arts because they provide for human needs and offer a way for us to serve others. This is true not only of our personal physical needs, but those of our families, friends, and communities. Considered in the context of the life of Christ who healed, fed, and met other’s needs as part of his ministry, skills that feed, clothe, protect, and heal others become ways of loving our neighbor.

A second objection to Hall’s thesis is that incorporating the common arts in the classroom detracts from teaching the liberal arts, which is the aim of education. In this vein of thinking, the common arts are reduced to vo-tech, job training, or hobbies. The tendency to contrast a liberal education with the practice of the common arts is ancient. The Spartan law-giver Lycurgus was said to have forbidden his people from practicing trades and manual labor which were to be left to slaves and were not appropriate for free men. Rather than pitting the liberal and common arts against one another, Hall follows the tradition of Hugh of St. Victor who believed both the liberal and common arts are essential for wisdom. In this understanding, the common arts are not primarily about money-making or only about meeting physical needs, but are among the many branches of learning that together make a wise person.

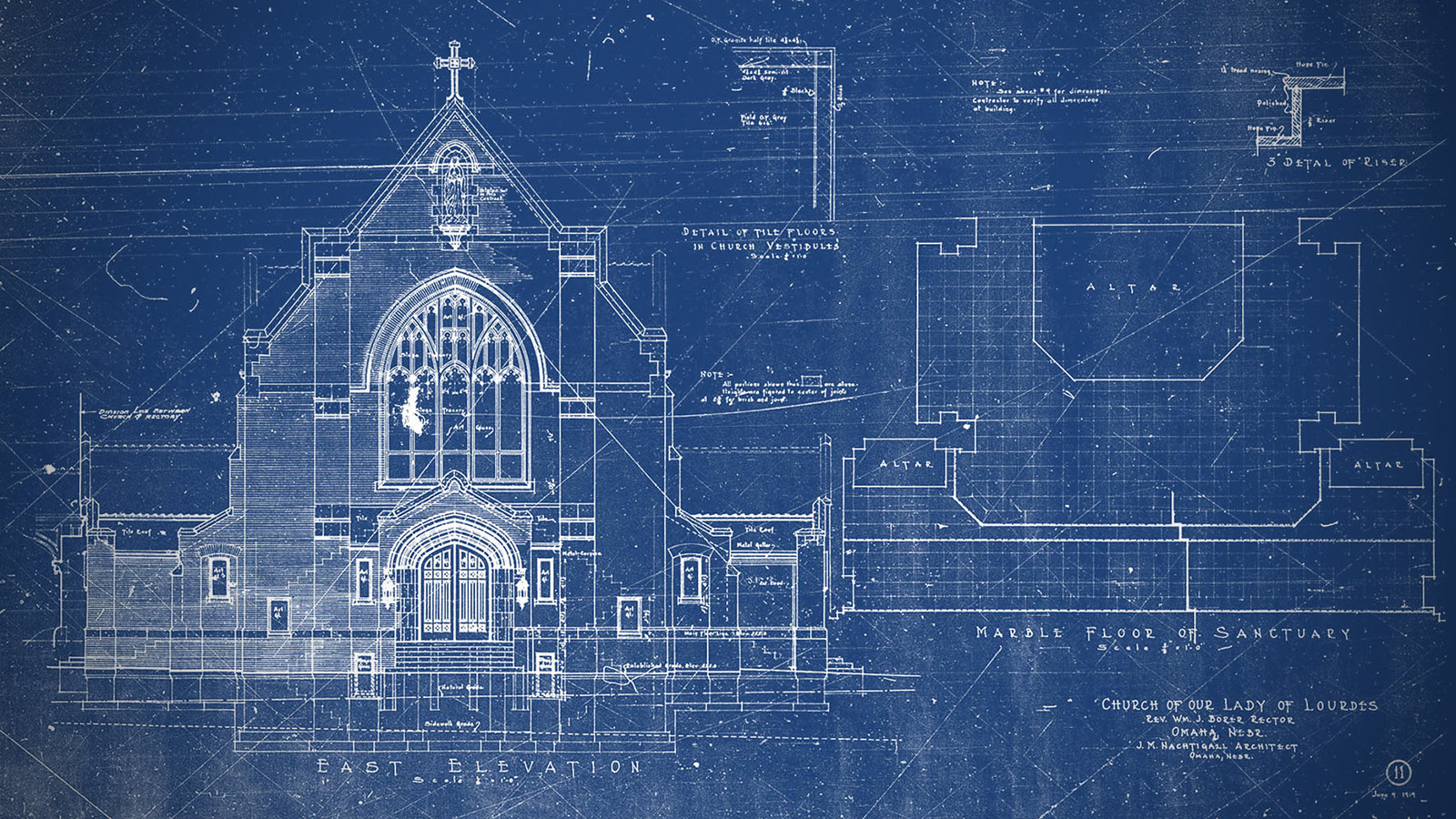

Not only are the two branches of knowledge compatible, but the common arts provide essential knowledge for the liberal arts student. As Hall notes, “It is hard to reason when there are whole realms of reality that one simply has not encountered” (32). Understanding historical events, great literature, and the philosophical tradition requires a basic familiarity with the common arts. I once taught a high school senior who insisted that Jesus describing the Father as sending rain on the just and unjust meant that bad things happen to all people. My student, living entirely detached from farming, understood rain only as an inconvenience, rather than a vital means for sustaining life, and therefore as a demonstration of God’s generosity. The common arts are inextricable from the liberal arts because it is through the common arts that truths work their way out in the material world. For example, the practices of woodworking, architecture, and trade apply the liberal art of mathematics, and our philosophical understanding of the body, spirit, and mind works its way out in how we practice medicine.

The common arts also join the liberal arts in setting their practitioners free. The liberal arts are so called because they are the mark of a free person. For the Greeks, this meant a person had to have the leisure to practice the arts, and that these arts were necessary for a self-governing people. For Christians such as Hugh of St. Victor, the arts of the trivium and quadrivium help free humans from the bondage of ignorance brought by the fall and restore us to the Wisdom of the creator. Without the liberal arts, we become enslaved to ignorance and the control of others, and our world narrows to meeting only our animal needs.

At the same time, being unable to practice the common arts entails its own form of slavery. Even with a liberal education, one is still handicapped without the basic knowledge and life skills provided by the common arts. “It is hard to be free,” writes Hall, “when one lacks skills necessary to survival and must rely upon artificial structures of business to provide for all basic needs” (32). This total dependence on external structures for all our physical needs seems to be unique to our own age. Unlike any other time in history, we can live our lives without ever having grown or cooked our food, raised an animal, learned to defend ourselves, or traveled to a location without an electronic device telling us where to go. In our pursuit of total freedom from the so-called servile arts, we have found ourselves trapped in a new form of slavery.

Perhaps the greatest hurdle to a widespread practice of the skilled arts is our own ignorance of the common arts. I may wholeheartedly support a renewal of the common arts, but how do I go about participating in this renewal with the constraints I face—the physical space of my classroom or home, the time limits of a school system or work or family life, and my own inexperience? Hall addresses these concerns in each of the thirteen chapters dedicated to a separate common art. After situating each art in its historical context and outlining safety considerations, Hall suggests how to introduce the art into the classroom through connections with other disciplines already being taught. Many of his suggestions could be applied at home as well. Additional sections describe in-depth projects and list additional resources including community organizations, websites, and books. His primary aim in writing his book is to overcome exactly this argument from logistics by walking readers through practical considerations for renewing each art.

While the book is written for educators, it offers opportunities for reflection for any reader. The common arts are domains of human activity that meet human needs. As such, each art touches on our daily lives. Take the art of medicine, which in pre-modern times focused on balancing the humors in the body. While humoral medicine is no longer practiced, Hall highlights three things this theory got right that our modern medical approach lacks—a focus on health over medicating everyone for everything, the focus on balance that the humoral system sought, and a holistic mind/body/soul approach to health and healing. By drawing from these ancient practices, we can gain perspective on our own culture and new insights into how to better live our daily lives.

Common Arts Education invites us to rethink our ideas about knowledge—what knowledge is important, how we know, and why we know. It makes a larger space in the classroom for tacit knowledge—knowledge gained through practice over time that can’t be summarized in a slide presentation or regurgitated on a multiple-choice test. Gaining this kind of knowledge takes time, and it shapes and changes the learner, even as the learner begins to shape and change the world around him.

A renewal of skilled craft in the classroom seems especially important in light of findings, such as those William Deresiewicz documents in his book Excellent Sheep, that students focused on the college admissions game experience high rates of depression and a sense of purposelessness (8-9). While there are many factors causing this, surely one of them is how disconnected education is from the physical and material world, and from the confidence, self-sufficiency, and maturity that comes from interacting successfully in that world. A person who can navigate remote wilderness terrain for five days and nights during a hunting expedition will have a stronger sense of her own strength and competence. Success in woodworking does not depend on an artificially constructed grade, but on whether the bookcase you made stands up and holds books. In both these situations, students’ success and competence are not granted by others, but are gained from proving themselves in the physical world.

A renewal of skilled craft in the classroom seems especially important in light of findings, such as those William Deresiewicz documents in his book Excellent Sheep, that students focused on the college admissions game experience high rates of depression and a sense of purposelessness (8-9). While there are many factors causing this, surely one of them is how disconnected education is from the physical and material world, and from the confidence, self-sufficiency, and maturity that comes from interacting successfully in that world. A person who can navigate remote wilderness terrain for five days and nights during a hunting expedition will have a stronger sense of her own strength and competence. Success in woodworking does not depend on an artificially constructed grade, but on whether the bookcase you made stands up and holds books. In both these situations, students’ success and competence are not granted by others, but are gained from proving themselves in the physical world.

Further, the sense of loneliness and disconnectedness that has only radically deepened over the past year can be bridged through the practice of the common arts. The common arts are best taught through apprenticeship—through physically working alongside another person. When so many of our interactions with other people are mediated through technology, the common arts require the physical proximity necessary for building deeper and meaningful relationships, a rootedness in a community of craftsmen, and a connection with a tradition of craft that goes back hundreds or thousands of years.

The common arts are a field where our physical bodies, our intelligence, and our virtue intersect with the realities of the material world. Sayers is again on point: encounters with the real and physical consequences of natural forces such as gravity teach us that we “must not worship [our] own fantasies, but pay allegiance to the truth” (12). In a world mediated through technology, the common arts bring us into daily encounters with a material world where we have not made the rules. They orient us to truths outside of ourselves and foster humility as we subject ourselves to realities beyond our control. By more fully rooting students in this world through the common arts, we might better give them the ability to extract themselves from the fantasies and disorientation of our technological mindset and to work out their human calling as embodied sub-creators who pursue Wisdom through all branches of knowledge.

1 comment

Joshua Pauling

Heather – Thanks for reviewing this important book. I heard Christopher give a Zoom talk about the book recently, and I found myself resonating greatly with the book’s themes. Uniting the liberal and common arts is a great interest of mine as well, as I run my own custom furniture business in addition to teaching. As you say, “The common arts are a field where our physical bodies, our intelligence, and our virtue intersect with the realities of the material world.” My wife and I have found there is great interest in recovering what I call “the skills of resilient living.” We host summer camps and workshop where we teach Home-Ec and Shop Class, and they fill up very quickly! (https://sites.google.com/site/daddysworkshopofthecarolinas/camps-workshops),

Cheers,

Josh

Comments are closed.