In a lecture on monastic stability delivered at the 2015 Front Porch Republic conference, Benedictine monk Gerard D’Souza noted that the idea of staying in one place for the rest of one’s life would probably strike most as “at best odd, and at worst terrifying.” But, he then asked, might it not be the case that those who cherish mobility so dearly suffer from “the anguish of inner instability”?

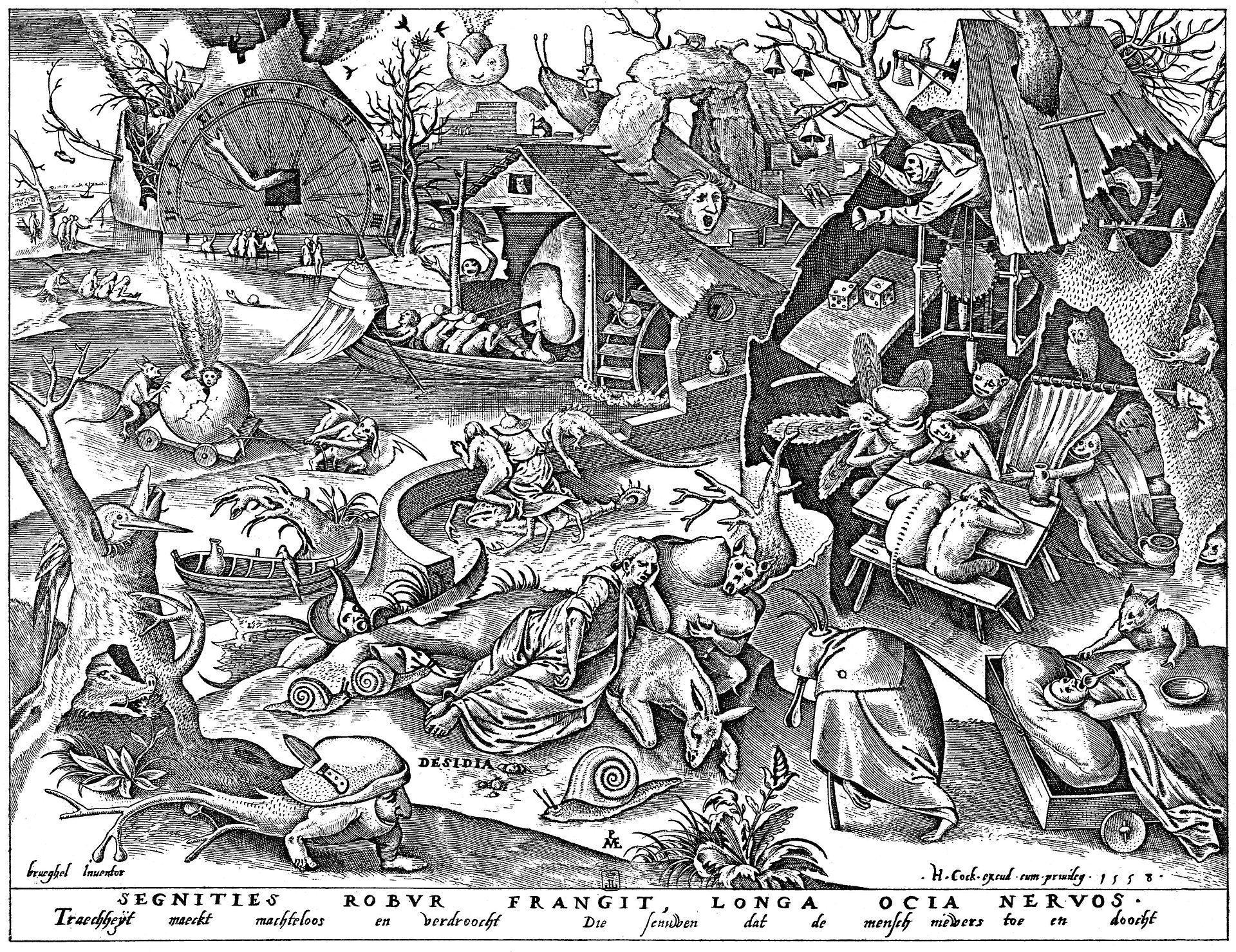

The pervasiveness of geographical instability in contemporary American society—wherein people often move multiple times during their life—has been observed by many here, along with the spiritual instability that almost invariably accompanies it. What I hope to do is say a few words about the deeper roots of rootlessness—acedia, or as Jean-Charles Nault calls it, the noonday devil—so that those who are restless in the place they find themselves, geographic or otherwise, might recover the peace of God they have lost or forgotten.

Nault writes that the Greek word akèdia—from which “acedia” is derived in both Latin and English—means “lack of care,” but he also notes that “every time we try to translate this term, we lose a bit of its richness: we speak about languor, torpor, despair, laziness, boredom, or disgust, but ultimately none of these words succeeds in rendering the wealth of connotations of the term akèdia.” This caveat should be born in mind, but for clarity’s sake it will be helpful to conceive of acedia, using Nault’s phrase, as “a lack of care given to one’s own spiritual life.” Or, to condense the idea even further, we can define acedia the way Reinhard Hütter does, as “spiritual apathy.”

The concept of acedia was first discussed at length by the Desert Fathers, those early “Christians who traveled to the desert so as to lead there a life of prayer and asceticism in solitude.” In particular, Evagrius of Pontus is identified by Nault as “the one who first presented a coherent doctrine about acedia.” Evagrius speaks of several different manifestations that acedia can take, but the one with which we are concerned here is what Nault calls “a certain interior instability,” which is “characterized by the need to move about, to have a change of scenery.” In this manifestation, says Nault quoting Evagrius,

The demon of acedia suggests to you ideas of leaving, the need to change your place and your way of life. He depicts this other life as your salvation and persuades you that if you do not leave, you are lost.

Given that Evagrius was writing to and for fellow monastics in the fourth century, we might wish to believe that the feeling of acute restlessness he describes is not a problem for ordinary people today. Unfortunately, as Nault observes, this experience is confined neither to the past nor to the monastic vocation. Rather, in the present, “This instability is manifested … by a constant need to move, to change. To change one’s locality, work, situation, institution, occupation, spouse, friends.”

Mirroring this geographic instability, acedia can also take on what Nault calls a “temporal dimension.” Unable to bear the present moment in which we find ourselves, we muse on what we take to be better times gone by, or else dream of happier things to come. Yet these ruminations yield but “a taste of bitterness and dissatisfaction.” Those afflicted by acedia may believe their salvation lies in an unending stream of novelty, but Nault, quoting Isabelle Prêtre, gives the lie to this notion:

One seeks, not fullness, but rather the accumulation of images as an evasion. Travel agencies proliferate. No one thinks of anything but getting away, but wherever he goes, he takes himself along. Now if emptiness, anxiety, boredom dwell within a being, this emptiness, anxiety, and boredom will follow him to the ends of the earth. The tenacious illusion of always being better off elsewhere does not abandon the individual. Anything seems preferable to self-awareness and diffuse pain.

So the sense of instability commonly felt today is a typical manifestation of acedia. But whence acedia, this spiritual apathy? How do we come to be in this condition where we seek satisfaction in lesser things that can never satisfy, searching for, in Nault’s words, “animal beatitude”?

Acedia occurs when, “Confronted with the grandeur of his vocation, man runs the risk of falling into despair and of never being able to accomplish it.” Drawing on Aquinas, Nault speaks here of our ultimate vocation to beatitude, that is, “the ultimate joy when, in eternal life, we will participate definitively in the very life of God.”

In our present life, however, where our continued sins weigh heavily on us, we can come to find it “impossible, given the infinite distance between the nature of man and the nature of God, that man could one day share the very life of God.” In such a state, as Hütter says, we fall into

The self-indulgent deception that there never was and never will be friendship with God, that there never was and never will be a transcendent calling and dignity of the human person. Nothing matters much, because the one thing that really matters, God’s love and friendship, does not exist and therefore cannot be attained.

From this conviction arises despair, in which we seek to “fill the void” with lesser things, one after the other, thus arriving at “a frenzy of novelty and, ipso facto, a horror of anything lasting, of everything that stays in one place.”

How, then, can we overcome the sickness of acedia? Nault, again invoking Aquinas, tells us that the very fact of the Incarnation dispels the monstrous fiction that communion with God is impossible:

In describing the Incarnation as the definitive remedy for acedia, Saint Thomas asserts that from now on the distance between human nature and divine nature is overcome by the Son of God himself. Fully God and fully man, Christ restores to us the hope of being able to participate fully in the divine life; he reopens for us the path to beatitude.

To state the same truth in terms of our sin, “From now on we are saved from acedia, because Christ has delivered us once for all from sin and from the resulting despair. The Incarnation is therefore the definitive remedy for acedia: it truly restores to us the joy of being saved.”

In the midst of despair, we typically take on “a semblance of humility: man asserts that he is not worthy of God’s love.” But as Nault points out, we can defy such despair by recognizing this “humility” for what it truly is – prideful presumption:

In reality, God is the one who loved us first (1 Jn 4:10), without any merit on our part (Rom 5:8). God’s love does not depend on our personal sanctity; rather, our sanctity depends on God’s love for us and should be our free and loving response to it.

We can remember this truth daily by appreciating in the Eucharist the very body and blood of Christ given to us, as Nault says. Additionally, per Hütter, we can also remember through “an active and persistent discipline of prayer.” (Practicing such a discipline consistently can be made easier by taking up an established tradition of liturgy, such as the Book of Common Prayer or the Divine Office.)

When we remember and make real to ourselves this truth, we can in turn apply it concretely to the place in which we find ourselves. So says Nault:

There is a love that precedes me and calls me; this love will never die, and I rely on it in order to remain faithful. Now this “abode of fidelity” is not somewhere else; on the contrary, it is precisely here where I find myself, at this moment.

Hence, we can be at peace in whatever place we are now, joyful in the knowledge that “our dwelling place … is also the place that God assigned to our life and that we ourselves have recognized and chosen at the moments of greatest clarity in our life; in other words: our own vocation, our specific calling.” God may one day call us elsewhere, but absent such a call we can reside in our given place and “live the present moment intensely, knowing that it is an opportunity to encounter the Lord.”

1 comment

Comments are closed.