Vilonia, AR.

It is Tuscany yellow. The room where her

Mind will not stay. His is Othello’s

Rage portending a thousand slaughters.

The sun has set. Death rehearses

Violent hours. She hopes in sleep,

Perchance to dream, to wish—to be

No more unsifted. She Knows not

What she shall be. A battered Bitter’d

Soul sings a dirge. Weep willow—

For Barbara as she cries.

“Come all you forsaken and mourn you with me,

Who speaks of a false love, mine’s falser than he

—for I may die with his wound.”

She fears she does not yet know Who.

He spoke no words, He heard none too.

His razor sharp, His cuts heal.

Made serene in His tempest. Wreck’d by the Quiet.

So begins the prologue of the literary memoir of a formerly good girl. Existential angst? Uh-huh. Crisis of meaning? You bet. Boethian? Most assuredly. “I find your writing is elegant, almost poetic at times—you have a real gift of written expression, it is obvious you are well read,” responded a major publisher. The manuscript outlined the bad fortune of a family overtaken by a number of disorders, betrayal, corporate espionage, AIDS, abandonment, patricide, filicide, suicide, and an eros that dare not speak its name. Like Boethius, who suffered grave injustices through no fault of his own, she was alone in a room with an almost disinterested stranger pondering the unlucky turn of a home destroyed. The misfortune is spiritual fodder for “all things working together for the good.” What is good? Surely, a book deal is good. But, the publisher urged her to “go back through it and make your points a little more starkly, but not luridly.”

Writing more like Cormac McCarthy and less like Tennessee Williams is a postmodern gifting that some of us do not possess. Telling “all the truth” is best done at a “slant” (as Emily Dickinson advised), and with a Southern drawl (as Flannery O’Connor would have it). For a good girl, “starkly” was undoable, even unthinkable. Why couldn’t I, like Joshua Gibbs in How to be Unlucky: Reflections on the Pursuit of Virtue (2018) “use my own life as a cautionary tale for others” (28)? Perhaps I was waiting for the last chapter titled “Expected Ends” to materialize (a la Jeremiah 29:11). You know, the one where you receive Job’s double portion of every earthly loss, the rainbow at the end of the storm, justice served, marriage restored … victory in Christ. Now that makes a good story! Instead—similar to Lady Philosophy—the Quiet is a buzzkill.

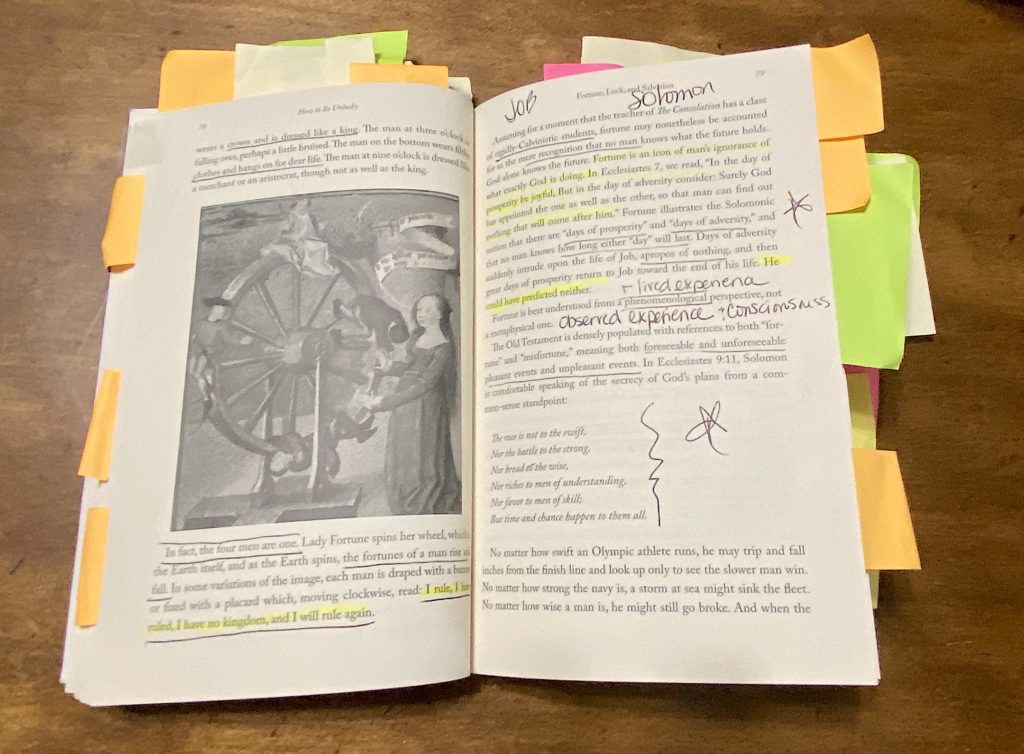

How to be Unlucky is about developing virtue, even when there is no happy ending. This was the predicament of Boethius, author of The Consolation of Philosophy. A Roman senator and consul to King Theodoric the Great, Boethius was unjustly accused of treason, found guilty, and executed. As a scholar and translator of Aristotle, Boethius informed centuries of great minds, and brought comfort to the afflicted. It was translated by King Alfred the Great at a time when vengeful Viking tribes sought to destroy a united kingdom; by Geoffrey Chaucer for a people fresh out of a Hundred Years’ War and the Black Death; and by Elizabeth I, the philosopher-queen who held the fragile balancing act of domestic and foreign tensions between Catholics (France) and Protestants (England).

These translations into common vernacular were a labor of love meant to help ordinary people in unfortunate times of desperation, confusion, and strife. Likewise, How to be Unlucky is the “gentle medicine” needed for common people in a post-modern world replete with warring ideologies, unrest in the streets, a global pandemic, and a loss of meaning as well as virtue. In the recent edition of Local Culture, editor Jason Peters’s introduction highlights Christopher Lasch’s The Revolt of the Elites (1994) in describing “the old aristocracy,” as retaining “many of its vices but none of its virtues.” In turn, they transformed the institutions into their narcissistic image. In Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Narcissus was captive to his own reflection which lead to self-destruction. COVID-19 isolation is symbolic of our lonely selves imprisoned within a culture anemic to virtue. As generations before us who lived during historically unlucky periods, we are positioned for a potential awakening to virtue.

In reading The Consolation, Gibbs observes that it is not just about helping those mistreated by men or suffering great undeserved injustices. It is also meant to pull us away from our habitual sins that cast us into darkened understanding, corrupted memory, and overwhelmed hope. A new pedagogical paradigm emerges that is more a “matter of confessing faults than modeling accomplishments.” To confess faults one must acknowledge they are at fault, and Lady Philosophy is eager to help. Boethius has “been wronged, but he is also wronging himself and God” (146). She is “a personification of wisdom…[who] comes to console, but also to accuse, teach, and rehabilitate.” Her interest is in Boethius “becoming good, even if he only has a few days left” to live (20). Gibbs uses Boethius’ example to illustrate how it isn’t always vice that crushes our dreams. Sometimes it is “hopes dashed on bad luck and unpreventable tragedy.” In a “world that unsettles us all,” (233) how do we learn to be good and unlucky? It is a modern-day dilemma.

Gibbs memoir/guidebook begins with semantics: what does it mean to be good? My Reformed faith emphasizes, as does Gibbs, “there is none good, no not one!” Yet on the day I found myself alone in that room, I thought myself a very good girl. A good wife. A good mother. A good friend. A good boss. A good partner. A good missionary. A good teacher. A good Christian. No lying, no stealing, no cheating, no drinking, no swearing, no bad movies, no video games, no secular school, and no sex before marriage! Written long before I met Lady Philosophy, my prologue is a picture of what Gibbs calls the “imprisoned soul” — the soul that is “postured against God” (20). Thus He is silent, for as Lewis reminds us in Till We Have Faces: “till the Word can be dug out of us, why should [He] hear the babble that we think we mean?” Boethius and I pitied our great earthly losses and counted them one by one, instead of counting our sins. Confession is good for the soul because it turns us toward God, face to face. Gibbs begins in humility by confessing his faults to us, as he does to his students. Ultimately, he helps them find freedom from their own self-imprisonment. The purpose of education is virtue, and the lesson begins only after a clean slate:

The more recently a conscience has been cleaned, the greater the student’s capacity to hear instruction in virtue…The guilty conscience, the state of mind born of constantly getting away with it, is a miserable Cold War story of mistrust, and epistemological nail-biter where the soul descends into a chaos of accusation and self-defense, loneliness and delusion. Man may get away with it, but he never gets away with getting away with it (141).

Like Lady Philosophy, Gibbs doesn’t allow the reader to escape unfinished business with God. His thoughts on the nature of being, personhood, and the “drafts” we make on “God’s being” illustrate his intellectual, philosophical, and spiritual depth. I too teach The Consolation to high school students, but after reading How to be Unlucky, I will never teach it the same again. “God, from Whom all being is borrowed,” is good, Gibbs writes. Lady Philosophy posits that Goodness and Existence are one. Therefore, without goodness, one ceases to exist (124). Good is no longer an adjective, but a noun. It is a person, a being. Lewis says it like this, “There is but one good; that is God. Everything else is good when it looks to Him and bad when it turns from Him.” It is the Augustinian theodicy of evil as an absence that piques our interest. Who doesn’t want to grapple with their own potential to be a “nothing?”

My own understanding of good (and evil) developed through literature at a time when I desperately needed to know why. At first, I thought an intellectual reason was essential to my well-being, and Lewis’ The Problem of Pain met that criteria. But Lewis is not content to leave his readers with reasons alone. Truth requires art for “reason is the natural organ of truth; but imagination is the organ of meaning. Imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old, is not the cause of truth, but its condition.” As Gibbs states, “Every great work of literature [can] be used as instruction” in virtue (23).

For this reason, I added Karen Swallow Prior’s On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life Through the Great Books (2018) to my literature course last fall. I already taught Flannery O’Connor, Mark Twain, Jane Austen, Edith Wharton, Cormac McCarthy, and Shūsaku Endō. They are six of the twelve authors Prior uses to illustrate the cardinal, theological, and heavenly virtues. Like Gibbs, my pedagogy included confession. O’Connor’s “Revelation” prompted me to admit I sometimes resemble Mrs. Turpin. I also found it easy to be irritated with Mary Grace, a student at Wellesley College. Yet, what if God is using Mary and the book (Human Development) she throws as a special Grace toward me? No reader gets literally struck by the hurled book. It is a metaphor for the “aim” O’Connor is taking at us with her stories. Prior adds to my guilt by pointing out the way Mrs. Turpin “always noticed people’s feet” because she looks down upon them (222). O’Connor’s violence is meant to save the well-read. Tattooed on my wall is a reminder from her that an English teacher’s responsibility is to teach literature without consulting a student’s taste, for their tastes are being “formed.” Prior gives the reader/parent/teacher eleven novels and two short stories as molds.

“Reading well is, in itself, an act of virtue,” states Prior, “it is also a habit that cultivates more virtue in return” (14). To read virtuously, one must read “closely” (15) she believes. Close reading is a holistic approach that entails annotation, identifying structure, literary devices (such as irony and paradox), and discovering patterns, symbolism, and metaphor. My first course in graduate school was on critical theory, which denies universal truth, metanarratives, and even rationality. The professor assigned Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park in which we were to discover gender, race, and class as overarching themes. We were allowed the traditional method of close reading only if we could make the case for a unified text. A paper on gender required only those sections that spoke to the specific issue, as well as easy-to-find contemporary critical sources. By working hard inside the text I avoided being inside the head of a modern critical theorist, but increased the amount of time and energy required for my thesis. Consequently, the emerging theme was the virtue of “constancy” exhibited by the steadfast Fanny Price. Constancy is essential to developing other virtues. Prior emphasizes that we are not reading just to be informed, as we do when we scroll through our phone apps or learn a new skill. We are reading to be transformed, which is one of the “greatest pleasures . . . born of labor and investment” (17).

Both Prior and Gibbs agree that ultimately virtue orients us toward one end, to “love God and enjoy Him forever.” Loving God is difficult; it too requires our attention in a culture that is constantly distracting us. And while virtue brings about human flourishing that can be observed from the outside, loving God requires us to remember who we are on the inside. It is the place where we are to be good alone … in the presence of One.

How to be Unlucky points to Solomon’s talks in Ecclesiastes with himself, and within his own heart (21). Listening to our “other self”—the one that honestly critiques our actions—is akin to what happens when we read a good story. King Lear’s tragedy was that he “knew himself slenderly” and this was the misfortune of Boethius. “Forgetting” was his ailment, not the false accusations against him. Not to worry, Lady Philosophy consoles the reader:

It is nothing serious, only a touch of amnesia that he is suffering, the common disease of deluded minds. He has forgotten for a while who he is, but he will soon remember once he has recognized me (1.2).

“Every kind of sin is amnesia” for the man who retains “a seed of love for God” states Gibbs (110). King David suffered “amnesia” caused by sin. Nathan the Prophet, rather than accusing the King, told him a story. David saw himself in that story and suddenly his “amnesia” lifted regarding what he had done to Uriah the Hittite. Because David loved God, he recognized the wisdom Nathan used to reveal his sin through the character of another. This fall, most of us will spend a lot of time at home, perhaps alone with a book. It is a perfect opportunity and circumstance to practice reading well, to locate yourself in the story as David did. In doing so, people around the world may awaken to virtue at a time when we need it the most.

Through her memoir Booked: Literature in the Soul of Me (2012), Prior released me from the guilt of seeking God “indirectly” through fiction. Like her, “God met me where I was. In the books” (199). While I grew in the virtues each narrative expounded, I felt there was something spiritually off about finding God outside the Bible or church. Someone who understood God’s silence only after reading Till We Have Faces (Ps. 50:21, Zeph. 3:17; Hope) must not do Christianity well. Still, I could not understand some biblical principles apart from stories. Lady Macbeth’s constant imaginary hand-washing illuminated to me the unpardonable sin (Mark 3:28-29; Justice). In killing the Christ-like “full of blood” King Duncan she believed, “none can call our power to account.” Murdering Christ in our heart leaves no more sacrifice for our sins and the “damned spot” remains. Shakespeare preaches a good sermon.

Covering a multitude of sin was never so beautiful as when Jim covered the corpse of Huck Finn’s Pap (I Peter 4:8; Love). I wept with Achilles’ “winging words flying straight to the heart” of King Priam (I Peter 2:17; Courage). Solomon’s difficult saying poignantly played out to the end in the life of Lily Bart in Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth (Eccl. 7:4; Prudence). And, when I make God in my own image, Browning’s Caliban Upon Setebos embodies my doubt (Ps. 50:21; Faith). On spiritual questions, I may not be able to point to a specific Scripture, but I can tell you a story. While Gibbs helped me define what it means to be good, Prior reminded me that some of us cannot “bear to respond to God directly.” His goodness can overwhelm a finite being. Literature is like a “cleft” in a rock where God passes by; it is where I hide when I cannot tell what I have experienced “starkly.”

[…] Published in Front Porch Republic: https://www.frontporchrepublic.com/2020/09/awakening-to-virtue-confessions-of-a-well-read-unlucky-go… […]

Comments are closed.