Jackson, MI. Last month, pictures of mailboxes being removed from intersections in the Portland area went viral on social media. Twitter pundits pointed to these photos as evidence of Trump’s campaign to dismantle the USPS in the runup to the presidential election. One Portland TV station tried to find out what was going on, and a USPS spokesperson said they were replacing old boxes, but the article about the issue is woefully sparse on details. A reporter for the Oregonian did some more digging, but the resulting article is nothing like a fully investigated account: it cites one resident, a Washington Post story, a USA Today story, and two USPS spokespersons. So what is actually happening? Is the USPS dismantling infrastructure in Oregon as part of a Trumpian conspiracy to steal the election? Or are social media users spinning a partisan narrative of their own out of routine maintenance or adjustments to postal equipment? Information about mailboxes in Portland is abundant, but in the absence of careful, responsible, on-the-ground reporting, its meaning remains murky at best.

This situation—with its glut of data and dearth of clarity—is just one example of what happens when local news organizations are hollowed out and shut down. Margaret Sullivan details this troubling decline in Ghosting the News: Local Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy. This brief book—less than 100 pages—surveys the multiple reasons for this decline, outlines its effects, and points to some promising new developments. The story of journalism’s recent collapse has been told often, but Sullivan’s focus on regional, locally-grounded news and her experience at both the Buffalo News and the more globally-oriented Washington Post enables her to frame these shifts and their worrisome implications in a compelling narrative.

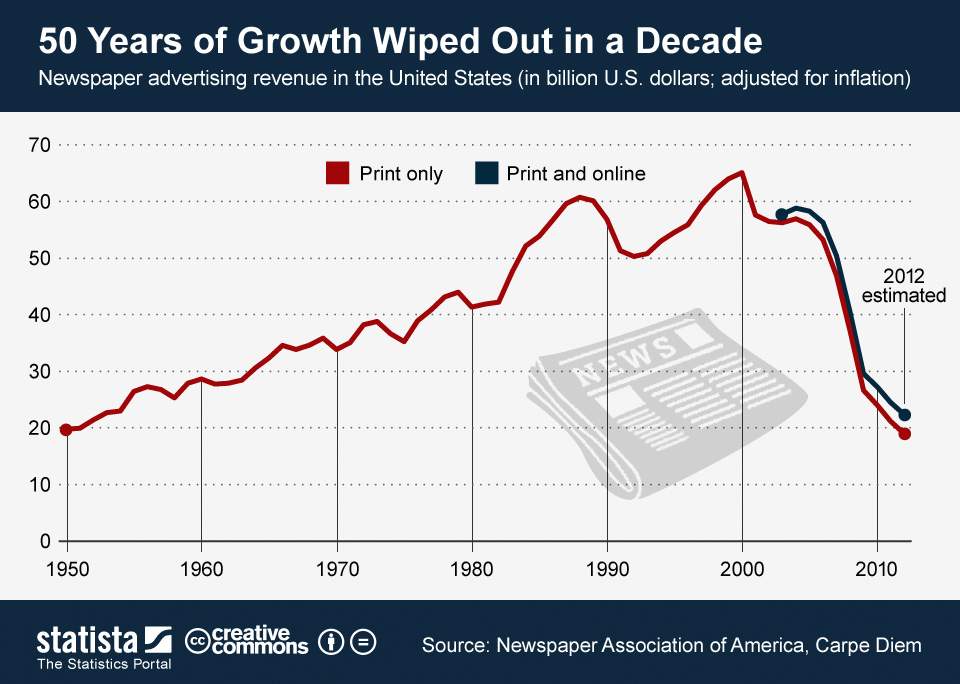

The picture that Sullivan sketches is grim: “American newspapers cut 45 percent of their newsroom staffs between 2008 and 2017, with many of the deepest cutbacks coming in the years after that.” Further, “more than two thousand American newspapers have closed their doors . . . since 2004.” This decline is particularly noteworthy because for many decades newspapers were quite lucrative. Monopoly papers, those without significant competition in a major town or metro area, often enjoyed 30% profit margins. Those margins were threatened as digital companies began competing for their revenue streams. First it was Craigslist cutting into the classified ads, and then Google and Facebook siphoned off advertising dollars. The 2008 financial crisis brought these challenges to a head, and things haven’t improved since. Sullivan cites a chart showing how newspaper advertising revenue in 2012 had fallen to levels not seen since 1950. The coronavirus, of course, hasn’t helped matters. News organizations furloughed and laid off many employees this spring as advertising revenue plunged again. Some organizations, from the Atlantic to the Texas Tribune, had turned to events to generate new revenue streams, and the virus wiped out this source of income entirely.

What happens when towns and regions no longer have robust local news organizations? It’s not pretty. Sullivan cites studies that show “less civic engagement, more political polarization, [and] more potential for government corruption” in the wake of newspaper closures. The Youngstown, Ohio Vindicator shut its doors in 2019, and the paper’s general manager told Sullivan this would have real consequences for civic oversight: “There was a time . . . When the Vindicator was able to send a staff reporter or a freelance stringer to every municipal board meeting and every school board meeting in the surrounding three-county area. ‘People knew that,’ he said, ‘and they behaved.’” This lack of accountability has real monetary consequences: “When local reporting waned, municipal borrowing costs went up, and government efficiency went down.”

The costs can also be seen in the rise of partisan voting. Voters in regions that lose their local newspapers increasingly vote by party affiliation. When citizens have no context for particular candidates, when there are no stories that explain the nuanced positions a politician takes on a given issue or describe their qualifications for office, voters have to make decisions based simply on the party a candidate belongs to. Of course whether a town council member, treasurer, or drain commissioner identifies as a Republican or Democrat is a poor proxy for knowing how competent they might be.

One of the consequences Sullivan points to actually helps reveal the broader cultural dynamics that contribute to the collapse of local communities and their news organizations. She worries that as local papers fold, larger publications will no longer have a deep bench of up-and-coming journalists with on-the-ground reporting experience. Sullivan is surely right that such practical apprenticeships are vital—and much preferable to the Twitter-feed experience that many contemporary journalists seem to prioritize—but strip-mining local papers for their talent is part of the ongoing colonization of small towns and rural areas. When money and attention get sucked into distant urban centers, the costs are borne by those left in flyover country.

As she surveys this bleak landscape, however, Sullivan does find some positive signs. Local public radio continues to grow, and stations are finding new ways to collaborate and share content. Nonprofit news organizations are testing new funding and distribution models. Some organizations are establishing shared bureaus in state capitals. Lean organizations print free papers with legitimate reporting and earn revenue through ads.

She also highlights an interesting organization in East Lansing, where resident Alice Drager helped launch a small news website, East Lansing Info (ELi). ELi trains community members to do basic reporting and pays a small stipend—often just $50—for each article. It’s a lean, inexpensive model that relies on a “news brigade” rather than a traditional staff. Drager told Sullivan, “When you create a news brigade, it’s amazing. You find out there’s a there there, and it’s beautiful. And nutty. It turns into home.” Sullivan concludes that this is one of the chief services local journalism provides: “the sense of community, of place, the role of news organization as a kind of village square where people gather to share a common experience.”

This description of newspapers as a “village square” recurs in Sullivan’s analysis. At their best, local papers “help provide a common reality and touchstone, a sense of community and of place.” Or, as she puts it elsewhere, “the newspaper ties a region together, helps it make sense of itself, fosters a sense of community, serves as a village square whose boundaries transcend Facebook’s filter bubble.” The paper is one of those places where a community can see its concerns and conversations reflected. It makes a place conscious of itself as a coherent place. Even advertisements in such papers are a unifying experience—everyone in a community sees the same ads printed in the daily paper, and the ads are mostly for local businesses. Digital ads, however, are narrowly targeted at individuals: the ads Google serves up alongside the article I read on my computer this morning are different from the ads my nextdoor neighbor sees. Further, ad dollars are less regional now that Amazon and other companies track down customers across the country and even the globe.

When the village square erodes, when money and attention are ever more relentlessly directed away from our places, we rub virtual elbows with people from around the globe. The resulting “global village,” as Marshall McLuhan names it, is a noisy, chaotic, and alienating no-place. As smaller, more local institutions wither away, individuals are increasingly left with nothing to mediate between them and the global public sphere. They may turn to some tribe of like-minded partisans to help navigate this disorienting space, but the result is not an embodied community. Rather, we occupy the global village as a collection of atomized “swarms,” to use Zygmunt Bauman’s term. In my own forthcoming book about the news, I elaborate on these dynamics, but in brief, such swarms are the result of humans seeking community in a digital space that cannot sustain responsible, embodied discourse and action. The global village is patrolled by Twitter mobs fighting over the meaning of ambiguous images. It is full of entertaining spectacles (if you’re into the theater of the absurd), but it’s hard to find the information we need to love our neighbors well.

Local newspapers haven’t always been altruistic, perfect institutions, but they have played a vital role in bolstering local communities and holding regional officials accountable. Having a paper land on your doorstep every morning—or even three times a week, as our local paper does—invites you to attend to what’s happening in your town. And if your attention is locally directed, you might be more likely to stop by the new restaurant you read about, understand why there’s construction happening at your neighborhood park, and show up to a council meeting discussing plans for new bike paths. You might even know where you can or can’t post a letter. Sullivan’s paean to local papers reminds us that even in a digital age, we need institutions to host regional conversations. Traditional newspapers may or may not be able to continue to play this role, but the health of our places depends on our ability to build and sustain institutions that can.

Surely you could have come up with a better example than the insane “Trump is destroying the post office to steal the election!!11!!!!!111!” derangement that no one even remembers. Whatever the lunatic-story-of-the-day from twitter is is not worth those of us in the real world paying any attention to.

Uh… I actually think the example was on-point. There was quite a panic about it on both my Facebook and the social media I do follow (not Twitter), and a serious dearth of actual facts. It’s the perfect example, sheesh.

Just trying to push back in one small way against someone who decided to slam you for mentioning something that MIGHT (not even did!!) put a Trump admin action in a bad light…

Comments are closed.