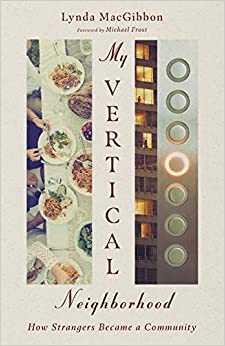

Ontario, Canada. The physical form of the communities we live in has a profound effect on our social lives. We are deeply social both by nature and in our practical existence – the idea of a solitary human must always be a highly qualified scenario. Our homes, shops, gathering places, and myriad enterprises are fused with the organization of our physical spaces whether at the scale of two chairs in a room or a sprawling metropolis of millions. Former journalist Lynda MacGibbon, in her recent book My Vertical Neighbourhood, writes about her experience as a newcomer to life in a high-rise condo in Toronto as she actively explores what it means to be a neighbour in the third dimension.

Throughout history, most neighbourhoods have been horizontal in nature. There have been densities of a few stories in old, historic communities where people lived very close to each other. The primary axis, however, remained aligned along a street or mall or corridor along which markets, shops, and services of all kinds found profitable flows of foot traffic. Modern engineering and industrial process has enabled us to turn those horizontal pathways into a relatively new vertical arrangement and repeat the process over and over until we have cities like Toronto, Vancouver, or Hong Kong. Not all density requires high rise buildings – Barcelona is an example of a city with very high population density. Many people today live in vertical neighbourhoods and MacGibbon challenges us to think about what kind of neighbourhoods they are.

One of the most valuable aspects of the book is MacGibbon’s newness to living in a condo tower. She writes about what is new and different about her vertical neighborhood. Contrasts are developed throughout her memoir as her thinking and lifestyle are shaped by the pursuit of answers to her simple question: “What does it mean to be a neighbour from the fifteenth floor of a high-rise condo?” Readers are given a chance to accompany her as she pursues answers to her new surroundings. I can relate. I grew up in a place even less populous than MacGibbon, living 30 miles from the nearest small town in Northern Alberta. I remember seeing The Towering Inferno when I was 10. It seemed alien. I had never been in a building like the one I watched on the TV screen and the idea of living in one was something I could only have compared to living in a hotel room. Such a scenario had none of the hallmarks of living in a community.

Vertical urbanism is gathering increasing attention, but the dynamics of life in residential towers has been around for many decades. G.E. Ballard’s 1975 novel High-Rise is one of many tales of an “all-you-want-out-of-life” luxury tower that falters into dystopian social erosion. Yet My Vertical Neighborhood is an important personal contribution to the many academic, popular, and artistic examinations of high density living and what the search for community looks like in such settings. MacGibbon may be new to this kind of living but according to the 2016 Canadian census, the number of people living in high rise residential buildings in Toronto continues to increase. According to the latest Census data in Canada (2016) more than 1.3M Torontonians live in apartment towers more than 5 stories tall. If that formal description is adjusted to include low-rise buildings, the figure is likely closer to 2.5M people.

Memoirs are characterized by recollections of experiences, perceptions, and personal dynamics. MacGibbon introduces us to what it was like to move from a rural property in Nova Scotia to a two-bedroom, fifteen story urban tower in Toronto. Her faith prompts a deep motivation toward neighborliness, a desire to live out the Christian mandate to love one’s neighbor. How, she wonders, am I supposed to love my neighbour here in this kind of place? The book is her answer to the question – not theoretically, not speculatively but concretely, intentionally, and personally.

This deeply serious living experiment was not haphazard – it was structured by clear intentions. MacGibbon introduces us to framing rules for undertaking the work. She chooses to engage her neighbours directly and literally as the people near her and does so by means of her own network of connections in her building and not working through her local faith community. Also important was her decision not to attempt to carry out the effort alone but to find an active partner in her friendship with Rachel, a young woman who ends up moving into the building. Finally, she makes a commitment to undertake her exploration of neighbourhood building by investing real and consistent time in the effort.

The idea of neighbourhood and therefore of neighbour can be complicated in many ways but actual proximity of one human to another human is central. We may know people online, in social networks supported by virtual interactions, or through common interests that span geography. If a neighbourhood is a network of support, then we can have them in a range of dimensions. MacGibbon’s decision to be literal in her understanding of neighbour (and the mandate to love one’s neighbour) moves her out from behind a protective wall of definitions and into the direct glare of the total strangers with which she begins her journey. The choice to avoid semantic side-stepping is courageous – my neighbours, she concludes, are the people I see in hallways, elevators, or pathways near my condo. For a small book oriented around a memoir styling, it was a good choice.

One of the benefits of being direct and literal is the immediacy of the writing that results. We meet real people in real scenarios and have a chance to accompany MacGibbon as she tries to figure out how to meet and then sustain relationships within a space usually characterized by passing greetings at best or brief, awkward moments in small spaces like the elevator.

Choosing to forego her local faith community as the primary point of entry into her neighbourhood means that she remains central in the story. She is the narrator and editor flagging the successes and failures without mediation of a program or formal collective group. This is one of the most telling dynamics in the book. An individual, motivated by fidelity to a core tenant of the Christian faith, simply seeks to live out neighborliness as clearly and directly as possible. A.J. Jacobs became famous for his somewhat sensational attempt to live out the Bible literally for a year. There is no showmanship in My Vertical Neighbourhood. It is honest, transparent, and vulnerable.

With no formal programs, church structures, ministry resources or oversight to pay homage to, readers will encounter a very real person they can relate to as she works her way across the kinds of social divides we can all relate to. You do not need to be someone who shares MacGibbon’s faith to benefit from the feelings of powerlessness, loneliness, struggle, disappointment and deep satisfaction that follows the long and steady labour that she and Rachel undertake together.

The other notable dimension in the book is the scale of social entities ranging from the personal to the organizational. Contemporary thinking assumes, as a starting point, that institutions are automatically harmful. If you read between the lines of MacGibbon’s story, you can easily see that social continuity beyond individual effort needs some form of collective process, a “container” that can sustain over time what is gained socially. Readers will do well to pay attention to the embryonic organizational and institutional forms MacGibbon’s experiment reveals. My Vertical Neighbourhood is a case study in the formation of social fabric under the unique constraints of a vertical living space. Institutions order time and resources. Rachel makes significant investments of time and energy every Sunday getting ready for the Monday night meal that the group shares together. They talk about, plan and then launch a a monthly Writers Group where people bring a piece of their own writing to share with other neighbours. There are many requirements attend to a range of interpersonal needs, complications and outright conflicts that consume time, energy, and focus. Busy schedules, life changes, people leaving, people joining and finding spaces to meet are not automatic or impromptu. Attention is required and not just episodic, “I feel like it” moments but the steady, ongoing labour that underpins so many of the great encounters in the book. Organizations sustain efforts beyond the individual.

The small social molecules of each apartment unit begin to combine and overlap as the people form an actual neighbourhood that eventually matures into a community. MacGibbon often reflects on the role of honesty and transparency in forging these growing connections. She had difficulty with that and asks herself: “Will I be honest and transparent with the people that I am building relationships with? What are my motivations in making the investment in these relationships?”

Building social worlds requires leadership. Groups need time and contact. This in turn requires initiative, persistence, self-awareness, and careful deliberation. Meaningful community rarely springs up spontaneously, and they are often really challenging. MacGibbon and Rachel had to face tough questions: Who is responsible when conflict emerges between members of the group? What happens when someone stops coming? Or when someone new arrives who is more socially abrasive than is comfortable? MacGibbon does not side-step these realities, which makes the book much more valuable than it might have been if she had decided only to share the high points. Writing in the context of a significant conflict between two key group members, she observes that:

Loving my neighbors could never be formulaic or dependent on never-ending traditions. I’d come to understand that loving my neighbor was about a posture of preparedness, a readiness to cross a threshold, about being present to people and allowing them to be present to me.

Many good intentions falter on the shoals of “them” needing “us” because the implied superiority always works its way into the fabric of the relationship, quietly nibbling at trust until stress reveals the flaw. Better, as MacGibbon reveals to us chapter by chapter, to face our common need for each other and accept what we have among us. This may not always be comfortable:

For a long time, I never told anyone about my loneliness. I wrote about it in my journal, thought about it on my long drives until eventually the feeling dissipated and I’d be back to my cheerful self. I was unable to tell anyone but myself about my need, but the need was real. I was the one in need of a neighbor’s love. It’s easy for someone like me to mask loneliness, even when it’s ripping a hole in my heart.

Mutuality matters. It is reflected through life in common spaces – condo towers, duplexes or suburbs. It emerges through common encounters – in elevators, hallways, carparks, and shops. It must also encompass common needs – for friendship, for love, for forgiveness, for hope. In this way, My Vertical Neighborhood is relevant to anyone living anywhere. The most translatable insight will be for people living in condos or apartment buildings but the challenge to cross an unseen boundary, to acknowledge that neighbors need us but that we also need them, to accept that social worlds are alive and therefore dynamic and growing but also capable of dying, this is our encouragement from MacGibbon.

The nearest homeless person pissing on the foyer planter has a richer social life than these morally bankrupt condo-lizards. Anyone who can afford to purchase a high-end condo in Toronto and join the HOA, can afford to live *anywhere* else. Mc’Scuse me. Why then? Why would you subject yourself to this impersonal, office-building type of existence? I’ll tell you why, because you *don’t want community*, you don’t want more than a passing glance or nod from anyone near your domicile. Otherwise, you’d live literally anywhere else… and it would be cheaper too. I find it reprehensible that someone with this much money is agonizing over the loss of something they purposely bought their way out of, at great expense. For the wealthy, the home often becomes an elaborate sarcophogus, and I’m glad for that. I have no sympathy.

An interesting notion here, one with which I have absolutely no familiarity, other than living for four partial years in a college dormitory (only three floors and a basement.) Otherwise, by choice, living in the same sort of rural “country” settings in which I was born and raised, even at the expense of better jobs.

One sad thought does pop up though, how long before most of humanity is living in the 50,000 person Towers of “Megacity One”?

Comments are closed.