It is often said that Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1839 essay, “Self Reliance”, is the real American Declaration of Independence, and to a certain extent this is true.

Emerson was a new Adam, and he deliberately proclaimed a new Heaven and a new Earth. Leaning on nothing but orphic speech and a confidence in direct revelation, this former Unitarian minister invited hearers to chuck prejudice to the winds, see the world for the stunningly present mystery that it is, and then walk out over a deep that only fearless people can cross to an unconventional, always original life.

Though Emerson stood squarely in the European romantic tradition, writing within earshot both of Wordsworth’s “Lyrical Ballads” and Beethoven’s “9th Symphony”, Emerson was nevertheless stubbornly American in his cockiness, his insouciance, his readiness to judge men vastly more learned than he could ever hope to be.

More to the point, he didn’t just see an absence of tradition, when he looked at “the woods”. Rather, he saw an apocalypse that all of history had been pointing toward — a kind of wildfire that philosophers somewhat lamely call “meaning”. Gothic churches with their stained glass windows and soaring ribbed vaults? According to Emerson, those architectural achievements were not so much an instance of “grace building on nature” as established religion gesturing toward the mystery that is a grove of trees, and by and large Emerson made good on his implied promise.

Emerson was tremendously popular on the lecture circuit, and when you thumb through “The American Scholar” or “The Divinity School Address” you see why. Reading Emerson you practically reside in a promised land. True, from time to time you have to come down to earth. But that is just to buy lunch or get some sleep. After those needs are met, you are free to go right back to where you were, for in Emerson’s brave new world there is no force pulling you elsewhere that you need to be “saved” from. All is bright, all is mega-text, and you can come or go as you please. But I question whether Emerson is all that indicative of mainstream American energy.

It seems to me that real American voltage, the kind that lights up whole cities and makes possible the cultural colonization of an entire globe, has more to do with revivalism – the phenomenon that shows up first in a small Moravian sect, then in the preaching of Jonathan Edwards, John Wesley, and George Whitefield, and then – during the first two years of the nineteenth century — in the specifically crisis-driven preaching of southwest Pennsylvania’s James MacGready and resulting festivals at Red River and then Cane Ridge, on the southern shore of the Ohio River in northern Kentucky. That is where the turbines really started turning, for that is where the requisite polarity lay waiting to be tapped.

Emerson? That seer transcended Calvinistic duality and to this very extent he was a sideshow. But — Cane Ridge? There, Calvinist principles got crossed with a frontier ethos in such a way as to enable a form of conversion so violent that it actually generated a hugely powerful, still functioning reversing current. My lord what a morning when de stars begin to fall. You’ll see de worl on fire, you’ll see da moon a bleedin. Shout, shout – we’re gaining ground. O glory hallelujah! We’ll shout old Satan’s kingdom down. Looking for America’s coming-out party? Your search is done.

It happened at Cane Ridge, on the very field those stars were shining on, and it continues to happen today, in a kind of third, slightly more managed great awakening, whenever people give themselves over to the beat and the charge and the sling-shot, ferris-wheeled glory of rock ‘n roll.

The Second Great Awakening, aka Cane Ridge revivalism, had its roots in the first Great Awakening, which began in 1733 when young, recently installed Congregationalist “scholar-pastor” Jonathan Edwards started experimenting with the repellent aspect to Calvinist nature-grace oppositions in Northampton, Massachusetts. Perhaps because he had studied Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica, Edwards was fascinated by “optix” and the reversals on view there.

At the same time, Edwards had thought a lot about “shocks of sense” and “hard pellets of sensation” owing to an equally absorbing interest in Lockean psychology. Hence it is possible that Edwards was literally conducting an experiment on his rapt, intensely credulous congregation when he slowly and deliberately brought the specter of sin close to the availability of grace, during sermons. In any case Edwards was a very skilled orator, and somehow or other he used those skills to maximum effect, for within the space of just a few years he had upended an entire town, ruined more than a few marriages, and got himself expelled from the pulpit. Had the Spirit stirred in the Pioneer Valley?

A lot of people thought it had, and they may well have been right, for only five years later similar waves of religious “enthusiasm” began to break across all of England and all thirteen of its colonies, thanks to the Wycliffe-derived, Moravian-influenced open-air preaching of former Anglican priests John Wesley and George Whitefield. Their tour was a sensation. (British invasion number one!) Large crowds turned out to hear them in town after town — crowds big enough to get observers like Ben Franklin thinking about revolution. But the biggest audience was still to come. It was the one Wesley and Whitefield never met, the one that lay waiting on the other side of the mountains. Thanks to their own outlaw status as exiled Anglican priests, Wesley’s and Whitefield’s act played particularly well to frontier-based Presbyterian “rednecks”.

Enter, now, Presbyterian minister James MacGready, steersman for the revival that Cane Ridge was modeled on.

MacGready was born in 1763, about halfway between Wheeling and Pittsburgh in southwest Pennsylvania. When he was a boy he had moved with his father to North Carolina backcountry, but an uncle spotted verbal talents crossed with a God-fearing disposition, and in 1785 James was back in southwest Pennsylvania with the uncle to study for the ministry. After obtaining a license to preach, MacGready gravitated once again to the North Carolina uplands, but after getting into trouble with presbytery officials there owing to an allegedly too zealous assumption of duties, he kicked the dust from his feet, said a prayer for disgruntled brass (“O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, thou that killest the prophets and stonest them…”), and hit the road (1796) for the wilds of Kentucky, where he asked members of his congregations sign a kind of covenant in which they mutually pledged to pray that God would bless them with “an outpouring of His Spirit” and “open the spiritual door at Red River”, thereby stirring up a revival that would “shake the nation and eventually the world”.

Pray they apparently did, for two years later strange things started happening after a communion service overlooking the Clear Fork Branch of the Gasper River. “How dreadful is this place,” MacGready said when congregants passed the cup. “This is none other but the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.” MacGready was quoting Genesis, mentally marking the spot where Jacob saw a ladder with angels going to and fro, but somewhere in the middle of his service hearers evidently took MacGready at his word and people got so distracted that fields were left untended for an entire critical week. That news got around, and thus it came to pass (one year later) that several hundred people convened at Red River for a three-day vigil, thereby kicking off the nation’s first “camp meeting”.

The date was June 13, 1800, and it is remembered for the large numbers of men, women, and children who fell down as if “slain in battle” over the course of the vigil.

That phrase was coined by Red River observer Barton Warren Stone, who went on to stage the much larger revival at Cane Ridge, and it is the source of the contemporary phrase, “slain in the spirit”, which is now common in Pentecostal churches across America and around the world as a label for that moment in an altar call routine when congregants fall down after the laying on of hands to become a kind of turf where cosmic forces do battle. At Red River, though, the event was not at all routine and observers like Stone were astonished. “The scene was new to me and passing strange,” he later wrote.

“Many, very many fell down as men slain in battle, and continued for hours together in an apparently breathless and motionless state, sometimes for a few moments reviving and exhibiting symptoms of life by a deep groan or a piercing shriek, or by a prayer for mercy fervently uttered.” No less amazingly, congregants also rose. They “shouted deliverance” and “declared” the wonderful works of God in tones that were “solemn, penetrating, bold, and free”. Can this account be true? Of course. Can it be trusted as a complete account? No. Though he appears to be an honest recorder, Stone’s commentary is lacking in that he never notes the violence of the images MacGready used to encourage hearers to faint with terror.

Writing for the Cumberland Presbytery office in 1835, the Rev. John Matthews remembered John MacGready as an old-school Calvinist who had “a talent for depicting the guilty and deplorable situation of impenitent sinners”, and this fact cannot be entirely unrelated to the force with which participants at the Red River revival fell and rose. Indeed, it goes a long way toward explaining that force, for just as Calvin discovered that floating the idea of “an elect” required the installation of a

doctrine regarding “total depravity”, so too (by the same token) preachers like MacGready were learning that you could start off with the conviction that you were damned and then discover a truly soaring experience of “election”, or release, upon

merely glimpsing the possibility that, owing to not knowing Jesus, you might have been wrong in your assumption that you were not one of the elect.

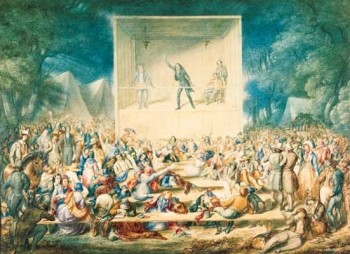

Which gets us to the revival that took place the following year just south of the Ohio River at Cane Ridge between August 7 and August 12, where participants explored the possibilities inherent in wild swings between “elect” and “damned” states like no other before and maybe even since. Thanks to the large size of the meeting house (the log structure could seat 500, including a gallery for slaves), and an alertness to precedents like communion “appointments” at Red River and similar, following ones at Concord and across the river in Ohio, Stone encouraged people to attend his carefully planned Cane Ridge meeting from very far quarters, and lo – they came. All told, 20,000 people showed up – a stunning number for a site in the middle of what was then nowhere – and therefore Stone quickly lost control of an event that he had hoped to guide. Before any one knew what was happening there were not just two or three but multiple stages manned by who knows how many ministers, some of them real and some of them a purer breed of entertainer, and after people started to “fall” even the official ministers started taking cues from what they saw around them rather than the ends their sermons were supposed to serve.

Think of the gathering, if you will, as a large ship illuminated by torches and driven by who knows who. Everyone had heard of this vessel thanks to reports of what had transpired at previous ports of call, hence (owing to the exciting nature of those reports) people had got on board, but now the huge boat was slowly and implacably turning toward a new kind of night and a new kind of day.

Perhaps it was the whiskey. Perhaps it was the suggestive aspect to the sight of young women falling. Perhaps it was the moaning of whole groups that were about to fall. Perhaps it was the exhilarating aspect to the presence of a crowd after months of solitude. Whatever the reason, the still present Red River dynamic shifted slightly to accommodate a new set of poles. Whereas in Red River the poles had been ideas about “sin” and “grace”, now the poles could also become sexual experience and spiritual dalliance above a time-chained earth, and as a result some of the congregants began to enjoy access to the same sort of maneuver Calvinist preachers enjoyed – that of bringing bodily desires close to heavenly ones not so much in order to integrate them or change the one into the other, but, instead, to accentuate, and better taste, the differences.

At Cane Ridge, it became possible for everybody to “feast” in this way, and feast we all did – first at subsequent, elaborately sober Methodist camp meetings that exploded across the Midwest, next at circus tents where Disciples of Christ sister Maria Woodworth Etter introduced a third set of poles having to do with the difference between ordinary time and lastness (Sister Etter’s audience switched from thinking in terms of Christ’s risen life shining through otherwise ordinary circumstances, to thinking in terms of Christ’s imminent return from a place that, presumably, was far, far away), then after that at Holiness churches in North Carolina backcountry and on Asuza St. in the Californian City of Angels where upraised hands curled like leaves on a burning tree and congregants surfed, vocally, on endlessly recurring waves of light, and finally at Assembly of God churches and then Catholic charismatic prayer groups where millions in countries as

diverse as Haiti, Mexico, Kenya, Poland, Ireland, Vietnam, the British Isles, Romania, Nigeria, Japan, Ecuador, Switzerland, and Samoa currently demonstrate proficiency in similar ecstatic arts.

What, you might well wonder, is this thing? What do we call a revival that starts out with a “slaying” in the trans-Allegheny wilderness and becomes a world’s fair? Most Americans – and now the world at large – call it rock and roll.

If you consult a dictionary or a musicologist you’ll probably be told that rock and roll is either delta-based rhythm and blues, or country music with a drum, or a fusion of Scots-Irish mountain music with African-American turpentine camp blues, but adherents to the first line of reasoning face the difficult task of proving that Presley’s appropriation of “hillbilly” music had little to no bearing on his more up-tempo obviously jump blues-based numbers, adherents to the second can’t account for the extent to which pioneering country artists like Hank Williams cut his teeth on the blues, and adherents to the third don’t recognize that Elvis’ “That’s All Right (Mama)” wasn’t so much the moment when two traditions fused as it was a moment when an artificial wall between “race records” and “hillbilly records” came down and a song that virtually all dispossessed Americans had been singing abruptly tightened, and well, got louder.

How though can we define rock and roll if not by thinking in terms of regional cross-fertilization and commentary about how Memphis is halfway between the the mountains of Tennessee and the Mississippi River? I submit that the best option for

defining rock and roll is that the music amounts to the juxtaposition of lowdown physicality (as expressed in blues played by both blacks and whites) against spiritual rapture (as expressed in gospel played by both blacks and whites). Can gospel, with its soaring flights of praise, really be associated with the insistent beat and double entendres of barrelhouse blues?

Though it is true that (a) they both employ call-and-response patterns, and (b) they both appeared at the same time (gospel, in its modern form, showed up and then gelled almost exactly when the blues did, thanks to the appearance of “southern quartet” arrangements in the 1910s, the genres appear to be pretty different. How, then, can one speak of a relationship between the two idioms? The key is that blues and gospel were linked but steadfastly not fused. Indeed,

they were carefully and even systematically brought close to each other and then kept apart in order to facilitate a reversing current that enabled both “poles” to intensify.

Clarksdale, Mississippi native Son House, for example, was a powerful bottleneck slide guitarist and blues singer precisely because he was formerly a Baptist preacher given to“revelating”. He had swung high, therefore he could swing low. Conversely, Hank Williams started out “honky tonkin”, as he called his blues tendency, and then (1950) switched to gospel tunes like “Just Waitin” and “A Picture From Life’s Other Side”. (When Williams recorded these latter songs, he released them under the stage name, “Luke the Drifter”.) Other popular musicians during this era didn’t so much emigrate from one side to the other as regularly oscillate between the two kinds of music. Witness Sister Rosetta Tharpe, from Cotton Plant, Arkansas, who became famous as a sanctified “shouter” while fronting Lucky Millinder’s jazz orchestra at night. Or consider the career of Thomas Dorsey, the man who wrote “My Precious Lord” and “Peace in the Valley”. This fellow penned practically every gospel standard you can think of, yet he also had a dual career as a pianist who went by the name of “Georgia Tom”. When he played as “Georgia Tom”, Dorsey was backed by “Tampa Red” on slide guitar, and their 1928 smash hit, “It’s Tight Like That”, defined “hokum” every bit as well as “Peace in the Valley” defined gospel.

To some extent, of course, this blues/gospel dynamic derives from the same marketing strategies that created “race” and “hillbilly” product lines. In the case of blues and gospel, though, there is an artistic commitment to keeping genres separate as well as a commercial one, and the existence of that artistic commitment is not unimportant. On the contrary it is crucially important, for its arrival portends a shift away from jazz, as a form of popular entertainment, to something that is, well, more sensational. Perhaps because of Creole roots, jazz is comfortable with enfleshment. It can “swing” and brim with smoky sensuousness. By the same token, however, jazz does not give itself over well to the kind of sexual energies that derive from a perception of flesh as “other”. It is rooted in ragtime, a form of music that indicates permissiveness and maintains an almost humorous detachment from the shenanigans that attended its birth in New Orleans brothels. Thomas Dorsey and Sister Rosetta, on the other hand, pledge allegiance to ecstatic experience. When these powerfully gifted artists entered a drinking or gambling establishment they sang like patrons rather than employees or staff, and as a result an entirely new form of music began to take shape which reached full bloom in 1954, pretty much when common wisdom says it did, at the moment Elvis Presley got recorded fooling around with session artists at Sam Phillips’ studio in Memphis.

Elvis had grown up attending an Assemblies of God church, and when he moved to Memphis at age 13 he started going to all-night “gospel sings”. At the same time, he spent a lot of time on Beale Street, where he learned the blues. Hence he was a prime candidate for carrying on the tradition begun by Dorsey. But Elvis took things a step further. In Elvis, the blues got so close to gospel that poles started switching back and forth within the space of a song, let alone a day, and thanks to his Pentecostal upbringing he had the physical abandon necessary to bodily go wherever the music did and thereby amplify those switches. It was a new thing, musically, and at first even his peers didn’t get it.

Take fellow Sun Records recording star Jerry Lee Lewis. That man packed a wallop, but he didn’t have the gospel side. He’d left that side of his life to first cousin Jimmy Swaggart back when they were growing up together in Ferriday, Louisiana, and as a result Lewis was in some pathological sense dependent on Swaggart’s Pentecostal ministry to fully live the rock and roll promise (just as Swaggart was apparently dependent on Jerry Lee Lewis’ kind of “devil music” to perform effectively as a minister). Elvis, though, had personal, uninhibited access to both poles. Elvis could go deep, then soar, and then (after holding for a minute, hips frozen, in crowd-pleasing transport) dig down and truly know the nit and the grit and the rut of ground. Witnesses were amazed. Even black “shouters” were amazed. Presley’s mid-1950s performances were literally electric, and the reason they were electric was that he had apparently tapped into the revivalist energy of old. Now it was the secular world’s turn to undergo an “awakening” — first by getting “rocked” with “a steady roll”, as per Trixie Smith’s risqué 1922 hit, and then by “rocking and reeling”, as per the old Kentucky spiritual and the 1916 hit, “Camp Meeting Jubilee”.

Same as it ever was, same as it ever was: dig low in order to then swing high and in that way keep lamps burning. This fuel isn’t midnight oil! Rather, it is an ongoing, apparently never-to-be-stopped reversing current that was ratified at Woodstock, made ready for export by record companies, and then — courtesy of the very same corporate machinery it enables – beamed out to the remotest corners of the globe. Move over, Max Weber! For that matter, move over Horkheimer/Adorno! The wonder isn’t that a Protestant ethic of thrift hatched capitalism, or that Led Zeppelin is selling Cadillacs.

Rather, it’s that Protestantism, American-style capitalism, and Led Zeppelin are all fueled on a hugely powerful, essentially non-integrative, systematically reversing electric current that only genuinely incarnational logic can interrupt.

I’m sorry but I don’t understand this piece of writing. Do I need to take something first?

Well, I don’t know, but toking dope is said to enhance musical perception and performance. On the other hand, you can take this as a Roman Catholic’s screed against Augustine and Calvin’s recognition that the human problem is not that the race was merely damaged by the Fall such that God could add some grace to the residual good in man and he could be redeemed by a cooperative venture, but the the race was rendered spiritually dead, hostile to God, unwilling and unable to please Him. This required God’s amazing intervention via the Incarnation of God the Son to give life to the spiritual zombies we became at the cost of the shedding of Christ’s blood on the cross in a torturous death designed for rebels to authority and criminals.

Well, that explains it. Thank you.

I should add that I don’t recommend use of Marijuana for a spiritual reason. The Bible condemns “Pharmakeia,” the Greek term for the use of drugs for sorcery or enchantment, i.e., as an avenue to contact demonic spiritual powers. Any mind altering substance can open you to demonic contact. Using alcohol to the point of drunkenness or even prescription pain killers can do the same. I discuss this at some length in my book, “Confessions of a Demonized Christian: How I received another ‘Jesus,’ then overcame the imposters” (available online at Amazon, B&N).

I should also add that the author is on to something real, that is, the spiritual aspect of sexuality that makes it quite dangerous even to those seeking and even encountering God through Jesus Christ. But the age-old connection of sex to Pagan worship, unleashed onto Western culture by the triumph of Rock ‘n Roll in the 1960s is no novelty. And just as sexual religion was used by Balaam and Balak to corrupt Israel, Rock music with its use of the rhythm of sexual intercourse has had a corrupting influence on the culture and, I believe, on Christian worship. Again, I discuss this theme in my book.

Uh… yeah… okay, skipping the other comments…

I think that you have articulate a genuine thread woven into our national cultural heritage, but not as strongly dominant as I think you mean. It does however inform my thinking about these things. Thank you.

Rock concerts are actually pretty lame when compared to a good-old-fashioned-Holy-Ghost-fire revival.

That includes the much over-referenced Woodstock, which I suspect our author here was not at.

Neither was I. The only person I personally know who was there was then and is now a fundamentalist Protestant. He’s about the squarest person you could imagine: an engineer, pocket protector, the whole thing. He rode up on his motorcycle, sat on a hill, listened to the music, and came home.

But life is complex enough, you can find what you want to find. When I saw Bob Dylan in Philadelphia in 1981, there was a group of Hell’s Angels a couple rows behind me, and a group of nuns–in habits–sitting in fron of me.

Bob rocked, by the way.

Very interesting piece. Many have written about the relationship between the religious sense and the aesthetic sense, but I’ve not seen it put quite this way before. Good stuff.

I am not equipped to evaluate the main thesis of this article, but it was fun, anyway.

I must object, however, to the statement that Cane Ridge is just south of the Ohio River. It’s 40 miles by crow if one goes straight north from Cane Ridge to the river, and quite a bit farther than that by bicycle from any place west of Cincinnati where I might want to cross the river.

It’s also interesting that some of the Campbellites (Church of Christ) who trace their origin to the Cane Ridge revival don’t have instrumental music in church, much less rock ‘n roll. Maybe some of the Campbellite factions allow it by now, but I think it was a point of controversy.

It’s also interesting that according to the web site for the Cane Ridge site, if you are part of a group that wants to hold a worship service there, you can do so, but one requirement is that it be “emotionally contained.” I don’t know if that means no rock ‘n roll.

For a couple of years I have been thinking of making a pilgrimage by bicycle to the site. A few years ago I was looking for sites of War of 1812 settler forts near Richmond, Indiana, and that led me to Elder Elijah Martindale, who not only had had some War of 1812 stories to tell, but had been a major figure in the early days of the Disciples of Christ. He married a woman whose father had been at Cane Ridge. I’ve visited the site of the Primitive Baptist Church where Martindale’s father was a member (he didn’t approve of the “rotten doctrines of Campbellism” that his son took up) and have stopped to chat with the present owner of the father-in-law’s farm. (One of my blog articles about these rides is here.) All of that led me to think I should do a ride to Cane Ridge, itself. In preparation I have read Ellen Eslinger’s 1999 book, “Citizens of Zion : The Social Origins of Camp Meeting Revivalism.” I should probably read more than that, so if you have any recommendations, I am interested.

Mr. Gorentz, the best book on this kind of subject is probably The American Religion by Harold Bloom (1992), but that’s top-down stuff, Bloom is not really building on historical research. If you prefer to ferret out the meaning of historical events by staying close to the ground and visiting actual sites, I suggest you zero in on how the Disciples of Christ hatched faith-healer Sister Etter — perhaps by cycling as well to the original Brush Run Church, which is where Campbell’s movement began, ten years after Cane Ridge. That site is twelve miles east of the Ohio River (as the crow flies!), on a ridge above Wheeling.

Books:

Holy Fairs: Scotland and the Making of American Revivalism, by Leigh Eric Schmidt

Cane Ridge: America’s Pentecost, by Paul K. Conkin.

The Great Revival: Beginnings of the Bible Belt, by John B. Boles.

Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt, by Christine Leigh Heyrman.

The Kentucky Revival, by Richard McNemar (a participant, who had already converted to the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Coming–the Shakers–when he wrote this)

Hey-hey-hey! Busy day, but I gotta chime in my praise for THIS fine provocation. As Martha Bayles or her teacher Albert Murray or his comrade Ralph Ellison could teach you, you just don’t have prayer of understanding the big family of Afro-American musics (“C+W” included) unless you grapple with certain BIG things that happened, in a subterranean way, back in New Orleans and Azusa Street just as the 1900s began. So sure, it turns out that you learn so much more about America from Ralph Waldo Ellison, as opposed to that earlier Ralph Waldo he was named after.

I’m not buyin’ into every lil’ bit of Mr. Hoyt’s theorizin’ here, but they’re very interesting bits–I suspect that idea of jazz’s ragtime-rooted detachment v. the pentecostal-rooted rock n’ roll desire to knock people OUT is going to haunt me, even if I wind up rejecting it.

For some of my own theorizin’ on such matters, this http://www.firstthings.com/?permalink=blogs&blog=firstthoughts&year=2011&month=07&&entry_permalink=carls-rock-songbook-rock-and-roll-patriotism, and this http://www.firstthings.com/?permalink=blogs&blog=firstthoughts&year=2011&month=07&&entry_permalink=carls-rock-songbook-the-who-wont-get-fooled-again-and-my-generation will serve as a start. One of my pet theories is that rock ain’t rock n’ roll. Most of Led Zep, for example, naw, it just doesn’t have that blues-swingin’ verve, let alone the church-wreckin’ FIRE, whatever other virtues it has.

And here’s some rock n’ roll for y’all. The Davis Sisters. Turn it WAY up, and prepare to be slain! http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2n3b3ajIMF0 Okay, if it’s a book you want (thanks all for the American revivalism sources) try How Sweet the Sound: http://www.amazon.com/How-Sweet-Sound-Golden-Gospel/dp/1880216191

I tip my hat to Mr. Hoyt–as Mahalia Jackson said after hearing Little Richard perform: “that boy’s been raised right!”

“Most of Led Zep, for example, naw, it just doesn’t have that blues-swingin’ verve, let alone the church-wreckin’ FIRE, whatever other virtues it has.”

“Them British boys think they play the blues real bad, but they play ’em plain bad.” Sonny Boy Williamson to Levon Helm

Mr. Hoyt, thank you for those leads. For several years I’ve been wanting to do a Whiskey Rebellion ride out to Washington County, Pennsylvania. Sounds like the sites you mention are nearby. You are right that I like to visit actual sites. I can get interested in a lot of historical topics, but if there are no bike rides to be gotten from them I tend to move on to something else.

Mr. Haas, thank you very much for that list of books to read.

Here’s a particularly extreme example of one revivalist preacher (Jack Schaap) giving a sermon about “polishing a shaft”.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tr0UpQXYkGs

Jack Schaap is Jack Hyles’ protégé. Ironically, Hyles and other fundamentalist Baptists of his generation frequently attacked rock-and-roll singers for performing with sexual energy (Elvis’ hips wiggling, and so forth). Yet what Schaap is doing in this sermon would put Elvis, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Alice Cooper to shame!

I am a Catholic convert from the Church of Christ/Christian Church denomination, one of many splits from the Cane Ridge Revival. I sometimes refer to myself as a Cane Ridge Catholic (with a wink and a nod). I had no idea of the elements of Pentacostalism (or call it what you like) that were inherent to that revival. The little white church on the hill I attended was as far removed and as distrustful of any hint of charismatic goin’s ons as they were of, well, Catholics. I suppose when the CoC split from the DoC we took the head and they took the heart.

I thank you for your article, sir. I’ll add it to my tiny bit of knowledge of my religious roots.

Comments are closed.