[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

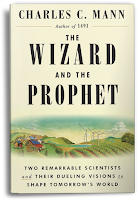

Charles C. Mann’s The Wizard and the Prophet, published earlier this year, is a fabulous book. Not a perfect book; sometimes, in order to bulk up this two-pronged thesis, he will throw in supplementary material that threatens to bog down his central investigation. But that investigation comes through loud and clear all the same, and it is one worth looking at closely.

Basically, Mann invites us to contemplate the (supposedly) inevitable end of the human species, and whether there is a way to escape that (possibly) biologically determined fate. He posits two alternatives, and picks representative champions of both. In the corner of scaling back and adopting smaller, more sustainable ways of living on the planet, so as to avoid ecological catastrophe, he chooses William Vogt, a little-known and often controversial but nonetheless pioneering figure in modern environmentalism. In the corner of science and technology, and the vision of ever expanding and improving our opportunities, he chooses Norman Borlaug, the somewhat better-known but still oft-overlooked (primarily because he wrote so little) partial father of the Green Revolution, and therefore the industrial agricultural system that today enables this planet’s resources to feed more than 7 billion people. It may not seem like a fair fight, and it’s pretty clear that Mann is on the side of Borlaug and technology (the “Wizards”). But he does a fine job laying out the warnings of those (the “Prophets”) dubious of humanity’s ability to always and everywhere grow more food, burn more fuel, build new things, and create new markets. For people who take the promise, or even the necessity, of localism seriously, whether for political or moral or environmental reasons (or all three), Mann gives us something vital to chew upon. Despite our collective affection for Wendell Berry (who is never mentioned in the book) and his warnings about how the promise of the new–new technologies, new jobs, new ideas–invariably causes people to lose touch with the wisdom of their limited, particular, embedded places, maybe localists in 2018 need Borlaug’s wizardly to pull off something like our hopes? Or do localists need to content themselves with standing with the prophets, all the way down?

Mann introduces us to his investigation in light of the work of Lynn Margulis, a biologist whom he knew and respected greatly, and who pithily described human beings as “an unusually successful species.” Unfortunately, in her view–and Mann basically accepts this, as a conclusion avoidable to anyone who takes seriously what the scientific method has allowed biologists to be basically certain about–successful species always end up in the same place: destroying themselves by exceeding the capacity and resources of their environment (which, in the case of human beings, is the whole planet). As Mann put it:

To avoid destroying itself, the human race would have to do something deeply unnatural, something no other species has ever done or ever could do: constrain its own growth….To a biologist like Margulis, who spent her career arguing that humans are simply part of evolution’s handiwork, the answer should be clear….All species seek to make more of themselves–that is their [biological] goal. By multiplying until we reach our maximum possible numbers, we are following the laws of biology, even as we take out much of the planet. Eventually, in accordance with those same laws, the human enterprise will wipe itself out. Shouting from the edge of the petri dish, Borlaug and Vogt might as well be trying to hold back the tide (pp. 35-36).

To people of a religious bent, who disagree that evolution’s logic fully imprisons human beings (even if they generally acknowledge the validity of the science which underlies it), this sort of talk often closes ears to the questions being asked. This is unfortunate, particularly in this case. While Mann never betrays any interest in non-scientific challenges to the laws and theories he is working with, he actually does do a much better job than most science journalists at keeping his readers aware of the conceptual limitations of the claims being made (he even has two whole appendices attached to the book, specifically considering all the problems with climate change research, though he himself completely accepts that global warming is both real, man-made, and a terrible threat). And more importantly, one has to get into a scientific frame of mind to understand the way in which the alternative paths that, as Mann presents it, Vogt and Borlaug sketched out shaped so many of the socio-economic and political debates over our day. So even if that isn’t the way you see the world, try to see it for the duration of this book; you’ll be rewarded, I think.

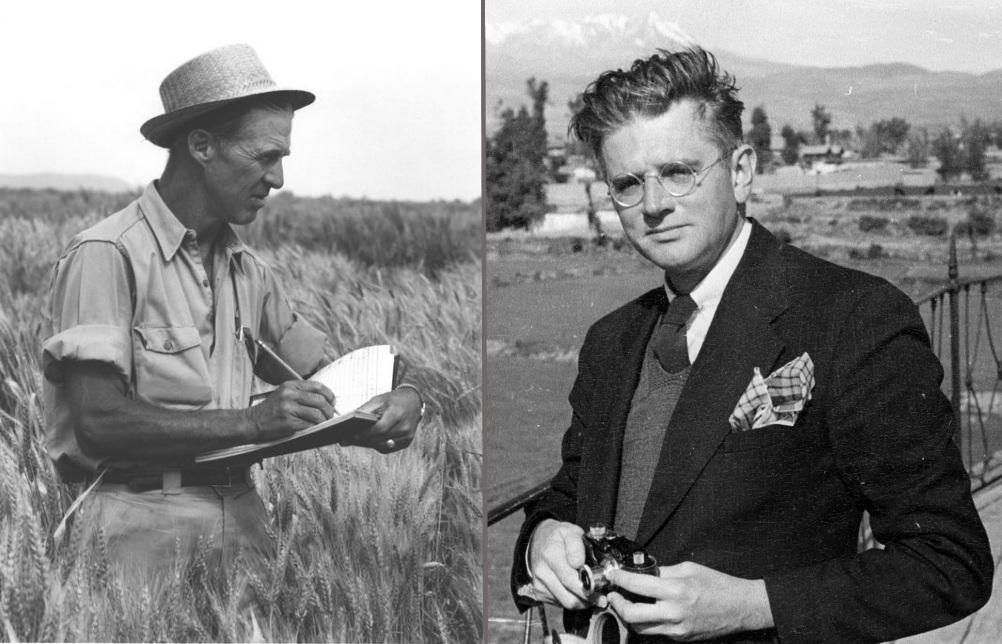

Along the way, you’ll learn about these two fascinating men. Both, in their own ways, were profound outsiders to their respective disciplines and intellectual cultures. Both, despite their respective educations, were significantly self-taught. Both were mostly men of action, rather than theory. Both were radical thinkers who were captivated by paradigm-shifting scientific visions (the catastrophic environmental consequences of unregulated industrial consumption and unlimited population growth, in Vogt’s case; the enormous agricultural possibilities of capital-intensive, industrially fertilized, genetically developed food resources, in Borlaug’s), and both of them came to these insights through endeavors that were ridiculously underfunded, mostly unnoticed, and utterly orthogonal to where the disciplines they came to shape were focusing (in Borlaug’s case, studying plant diseases in a generally ignored Mexican experimental station; counting guano-producing birds in total solitude on islands off the coast of Chile, for Vogt). They only met once, in an unproductive wheat and maize field east of Mexico City in 1946, where Borlaug was slowly hatching ideas about how the proper technology could make even that dusty, parched farmland productive, and Vogt was growing horrified at the idea that human beings never retreated before the kind of obvious environmental limitations he saw in front of him, but instead insisted on finding was to change or transcend them. They are almost certainly not the best possible examples of “apocalyptic environmentalism” or “techno-optimism,” but they were fascinating shapers of those movements nonetheless.

After sketching out their lives and insights, Mann applies their perspectives to four environmental limitations which our species–which most demographers currently think is on track to top out at around 10 billion people by 2050–faces: food, fresh water, fuel, and the climate consequences of pursuing growth in all of the latter. The observations and conclusions of these chapters–though often thick with scientific jargon–are sometimes surprising. (Mann, for example, comes to the conclusion, after running through the long history of always-disproven oil shocks and panics, as well as the endlessly inventive ways humans have developed to find, retrieve, use, and restore oil, coal, and natural gas resources, that as a practical matter, “fossil-fuel supplies have no known bounds,” thus dismissing peak oil in a sentence–p. 282.) They are mostly important, though, to show the breadth of the implications of committing to either the Vogtian or Borlaugian path–and for localists like myself, it is the former that seems the incumbent, rather than the latter. The one passage from the chapter on food captures the distinction between the two visions particularly well:

Which [type of farm] is more productive? Wizards and Prophets would disagree about the answer, because they disagree about the question. To Wizards, the question means: which farm creates more calories–more usable energy–per acre?….Every attempt to sum up the data that I know of has shown that in side-by-side comparisons, [small-scale, sustainable farms] grow less food per acre overall than [industrial-style, monocultural] farms–sometimes a little bit less, sometimes quite a lot. The implications for the world of 2050 are obvious, Wizards say….Prophets smite their brows in exasperation at this logic. To their minds, evaluating farming systems wholly in terms of calories produced….[ignores] the costs of overfertilization, habitat loss, watershed degradation, soil erosion and compaction, and pesticide and antibiotic overuse…[and] doesn’t account for the destruction of rural communities….

The difficulty is that both arguments are correct on their own terms. At bottom, the disagreement is about the nature of agriculture–and with it, the best form of society. To Borlaugians, farming is a species of drudgery that should be eased and reduced as much as possible to maximize individual liberty….The farm is a springboard, essential as a base, but also a trap. [Small-scale, sustainable] farms may mimic natural ecosystems, but they are also ensnared in them, unable to rise above their limits. To Vogtians, by contrast, agriculture is about maintaining a set of communities, ecological and human….It can be drudgery, but it is also work that reinforces the human connection to the earth. The two arguments are like skew lines, not on the same plane (pp. 209-210).

Anyone who has ever engaged in arguments with friends or foes (or family!) over anything pertaining to limits has probably felt the reality of those diverting skew lines. You argue about whether you should shop at Walmart or the local farmers market; the evidence on one side is about personal affordability and convenience, the other is about community health and ecological diversity. You argue about whether you should help your son buy his first car or insist he continue to be use his bicycle; while he talks about personal freedom and opportunity, you’re talking about environmental impacts and long-term costs. You argue about how you should vote regarding a proposed cutback in city funding or regulations regarding bicycle paths; the supporters are focused on everything that you can choose to do with the tax money you save, whereas the opponents speak of civic pride and future generations. And so it goes. Shopping local (and thus missing out on cheap deals), mending your own clothes (thus failing to impress the visiting corporate bigwig), staying close to home (thus losing out on the job opportunities in the next city over)–these and thousands of other arguments, even when they have nothing to do with anything that specifically relates to our use of the natural environment, can be productively understood, I think, in light of the skewed perspectives of Vogt (“Cut back! Cut back! was his perspective. Otherwise, everyone will lose!“) and Borlaug (“Innovate! Innovate! was his cry. Only in that way can everyone win!“–p. 6)

As one might guess, in a world where capitalist expansion and technological innovation is almost always celebrated (and industrial costs almost always either apologized for or shoved off for our children and grandchildren to deal with), Borlaug, in the due course of time, was celebrated, winning the Nobel Peace Prize and being praised around the world, while Vogt’s later years consisted mostly of frustrated in-fighting among small organizations for often smaller stakes. But I should rein in my grousing, no matter how deep my Vogtian, “use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without” sympathies. After all, Borlaug’s vision, and the whole panoply of efforts and ideas that have filled grain elevators and food pantries around the world, has resulted in tens of millions of people being alive today that almost certainly wouldn’t have been otherwise. And isn’t it likely that those tens of millions of lives have meant–often, anyway–tens of thousands of families, villages, and communities, creating their own cultural forms which have added to the excellence of human life, completely aside from the obvious moral imperative to help people live rather than suffer and die? While a more complete picture of Vogt’s aims (which Mann provides in detail) would include not only how he became entangled with–and partially agreed with–some of the worst advocates of population control and enforced sterilization later in his life, but also how his vision aligned some aspects of environmentalism with the old, often racist, aristocratic and anti-industrial “alt-right,” if you will: those members of the political and business elite who have never seen any good reason to pollute the world and break up established traditions in name of lifting up (or even just properly feeding) the masses, since most of those masses are probably uncivilized, un-Christian idiots, anyway.

But no–even with all those caveats, even while acknowledging all the ways that the technological empowerment of the individual and the spread of industrial solutions have saved lives and made the world a better place for hundreds of millions, I remain Vogtian at heart–my vision of the good life values “a kind of community” over “a kind of liberty,” and is much more amenable to the notion that we have to be “tied to the land” than to the belief that progress will always leave us “free to roam the skies” (pp. 250, 362). The differences between Berry’s agrarianism and Vogt’s conservationism are deep, though; the Vogtian perspective is one that is filled with solar panels, crop diversification, reforestation, graywater reuse, drip irrigation–much that goes far beyond Berry’s insistence on “local knowledge.” (Though, to be fair, most of the sustainability-minded approaches to feeding and fueling billions of people are far more ground-level and participatory than the Borlaugian “hard path” of massive desalinization plants and deep-water oil wells.) Embracing the gospel of less, of the small and local and communal, need not oblige one to deny the talents and blessings that specialization has brought.

As with all hypothesized dyads, practical wisdom necessitates that even creatures of limits recognize the openings which science have brought us, see how those have changed our daily lives, and think responsibly about how to sustainably make use of them. Perhaps Vogtian localism would find a perfect match in the “do-it-yourself futurism” that characterizes the work of economists like Juliet Schor. Perhaps a half-century of growth in statist and capitalist Borlaugian systems–the top-down impositions of industrial agriculture and wireless networks and interstate highways and the global marketplace–has by now reached far enough that individuals and communities really can use them to create, in their own particular places, specific and sustainable paths towards the good life. I’d like to think so. If we are to escape the species extinction that Mann assumes would normally be our biological destiny, then I would like our escape route to look more like one of Vogt’s envisioned patchwork of communes, than Borlaug’s endless rows of nutritious, delicious, genetically modified corn. (Though I’ll still eat the latter, sometimes, same as all of you.)

Thanks for the review. Sounds very interesting. One question–does the book contain any of the sort of climatic doom-and-gloom “don’t have children, because the world is doomed!!!1!!1!1!” hysteria that is unfortunately common in a certain set of environmentalists these days?

“To Vogtians, by contrast, agriculture is about maintaining a set of communities, ecological and human….It can be drudgery, but it is also work that reinforces the human connection to the earth.”

FPR should advocate for a New Homestead Act. The federal government still owns vast tracts of the West. I think it would be salutary for the nation if it was given away to homesteaders. We could preferentially give it to poorer people, who commit to an extensive training process to give them some chance to succeed, and provide an initial stipend as well. The costs would be trivial compared to the size of the budget.

Brian,

In regards to your first question, only to the extent that Mann notes the degree to which Vogt himself, over the last 10 years of his life, was often sucked in by such rhetoric. Mann himself doesn’t explicitly weigh in that issue, but he clearly doesn’t grant the “zero population” stuff from the 60s and 70s any validity; towards the end of his profile of Vogt, he describes him as having “wasted” years being “distracted” by population fears, in contrast to working on other issues. In regards to your second, I think I love the idea of a New Homestead Act idea, at least in principle. I’d have to think about how one would propose to make it work in our present globalized, industrial food-system context.

It looks like this book explores the same ideas that are dramatized in Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, which, unfortunately, dissolves the tensions too simplistically in favor of the Wizards by the end. At first I thought they would give more voice to the Prophets, but by the end it’s just Matthew McConaughey purring “we’re still pioneers….” Thanks for an excellent review!

Regarding a New Homestead Act: one significant problem for any variation of that proposal is that the public lands in question–most are west of the 98th meridian–are generally arid or semi-arid and would require irrigation, which comes with its own set of problems (requiring Wizard solutions). Apparently the data are hard to corroborate, but some scholars estimate that the failure rates for the original Homestead Act were as high as 50%. I haven’t had a chance to read it yet, but Brian Q. Cannon’s Reopening the Frontier: Homesteading in the Modern West would likely clarify the issues at stake.

Matt, strong agreement with your second paragraph. I really DO like the idea of new, different kind of Homestead Act, but if it solely focused on land controlled by the federal government in the American west, then you’d almost certainly be looking at huge failure rates, even with all sorts of improved technologies and approaches since the 1870s, which–as I noted in my review of the Laura Ingalls Wilder book–wrongly posited the dream of Jeffersonian, yeoman independence for a part of North America where the only really successful farms were big collectives run by extended families…a pattern which arguably industrial agriculture has inherited (as Robert Wuthnow has kind of implied). So Homesteading today needs to be of a different, more New Dealish sort. Large, family-based capital grants to set up farms and businesses in downtown Detroit and the outskirts of Cleveland? That might be more like it.

This is FPR, so let’s throw practicality out the window for a moment. Getting people “connected to the land” through direct involvement in farming, etc., is supposed to be inherently good, right? If we can all think Wendell Berry is great for advocating massive subsidies for tobacco farmers (I don’t actually), I don’t see why we can’t think seriously about a plan that tries to create several hundred thousand small ranchers.

The federal budget is much, much, much larger than it was when the various Homestead Acts were in place, and our view towards the welfare state, etc., is much different, which can change how a New Homestead Act works entirely. The federal government alone spends well in excess of $10B EVERY SINGLE DAY. You could easily give a lot of people a lot of training and subsidies for a number that sounds large but is trivial in relative numbers. I’d propose a multi-year traning and preparation process for applicants, then support subsidies, rules preventing sales & consolidation, and an iterative learning process to determine how to improve program success rates.

Fair enough, Brian. If we could imagine the levels of investment which currently exist to fund mandated social programs and the military-industrial complex being redirected to housing the American people in homesteading sites across the arid American west, then yes, we could plausibly imagine creating the kind of local training and technology sites such that every one of these homesteading communities could have working solar power arrays, deep water wells and extensive drip irrigation systems, hothouses to support hydroponic crops, etc., none of which would necessarily have to be dependent upon inevitably condescending experts being helicoptered in every other week. And presumably, once people actually put down roots in such places (if they do–but maybe comprehensive broad-band internet would lessen the feeling of isolation, thus encourage people to stay put, to say nothing of subsidies to make it worth their while), they would discover what all sorts of 19th-century homesteaders–those that actually survived in their places, that is, which wasn’t many–discovered: that there is a great beauty and bounty in the arid plains and mountains of the American west, if they can just look for it. It’s a pipe dream, obviously, but I can think of much worse ones.

A pipe dream, to be sure, but that’s why it’d be good for FPR and not, say, the United States Senate. Yet.

I could be wildly wrong, but I think you’re off by an order of magnitude in what it would cost. I think for $10B a year for a decade, say, you could have quite a program, which is chump change compared to social welfare or defense spending.

It sounds like a new variation on the Civilian Conservation Corps might be the better model to achieve some of these goals, and it’s not even that much of a pipe dream. The Onondaga Earth Corps in Syracuse, New York has been working in that tradition since 2005 and is still doing well. It was also founded in Syracuse for Syracuse, and has a diverse base of funding and income:

http://www.onondagaearthcorps.org/

I actually live near Syracuse. Syracuse does not need a federal jobs program. A huge fraction of businesses in the city have “Help Wanted” signs posted at all times. There are lots and lots of things that could help Central New York, but a new CCC is not on the list.

[…] [Cross-posted to Front Porch Republic] […]

Comments are closed.