Waco, TX. Cormac McCarthy is dead at the age of 89. An obituary is supposed to offer words about the man and his work. But that is hard in this case because McCarthy offered little about the man himself to the public. His ex-wife once recalled, “someone would call up and offer him $2,000 to come speak at a university about his books. And he would tell them that everything he had to say was there on the page. So we would eat beans for another week.”

Hence, what little writers can learn about McCarthy the man comes from borrowed anecdotes like this. Profiles, reviews, and now obituaries pass these along like trafficked artifacts, some of which might be forged. Not that I have reason to doubt. Only, “the story gets passed on and the truth gets passed over,” as No Country for Old Men’s Sherriff Ed Tom Bell once warned. Still, what excitement and mystery in the trafficking: he lived in a barn he built himself outside of Knoxville, observed whales in Argentina for a year, spent much of his Genius Grant on a stay in Ibiza, once conspired with Edward Abbey to re-introduce wolves into New Mexico, and for years lodged in hotels, ate off hot plates, and stayed five steps ahead of any glory trying to chase him.

The trafficking shows there might be a lot to know about McCarthy, after all. As it turns out, he gave plenty of interviews throughout the early years—only to local papers, not national presses. McCarthy contained multitudes, among them one of our nation’s greatest writers, and one who couldn’t care less.

As for me, I came to see two men in McCarthy, both in the work and in the man—make it four, then.

The first was the great Southern macabre aesthete at work. He reveled in the debauched vagaries of the Scots-Irish legacies of Faulkner. No circumstance too damned, no relationship too foul, no setting too smelly, for him to wax on about as eloquently as if he were commissioned to add pulp fiction to the King James Bible. This was the McCarthy of Outer Dark, Child of God, above all Suttree and Blood Meridian (though the latter was set in the West), with remainders scattered throughout the rest of his work, including his second to last, The Passenger.

This McCarthy, though often hailed as the writer at the height of his technical skill, showed hints of excessive influence from the Oxford (Mississippi) don. He also rarely indulged in a straight plot. These books, again Suttree foremost, would build their characters by meandering in such circles of time which might have delighted Nietzsche but leave others a little cold. I don’t mean nihilism. There is dignity and beauty in even the bleakest of these novels. There is just so much weight put upon the surface, the words and their intricate workings, while the characters betray signs of deeper—what? —just beneath. McCarthy is sly enough to keep the surface holding, so you cannot break through. This McCarthy is a pretty good time, and a pretty bad time, and he leaves you excited with big words and some big ideas, yet wanting more.

Now for the second McCarthy, the public man. He would shrug his shoulders at everything you’d be so excited to talk to him about. This was the McCarthy of his interviews. He didn’t like writers or think so highly of writing. He didn’t indulge much in his work or method beyond, “read.” A reader of Wittgenstein, he gleaned from him a deflationary demeanor somewhat common among Wittgensteinians. (In that respect, McCarthy shared a tic with another reader of Wittgenstein, the director Terrence Malick, who also shuns the public eye and, when rarely in the spotlight, offers little beyond simple replies.) So, he answered questions curtly and often left his interviewers to become monologuers, with him sitting beside them, a little embarrassed. Why was he interested in geniuses and theoretical physicists? “Smart people are fun.” What does he think about his life? “I’ve been very lucky.” About the meaning of life? “I agree that it’s more important to be good than it is to be smart. That’s all I can offer you.” About the unconscious? “It doesn’t really care about anybody but you.” About the state of the world? “Ah, that’s not a subject I’d be that happy to talk about, I just think, right now, today, is a, a very dangerous time.” On the question of intention in the universe? “Oh, I have to plead ignorance, I’m pretty much a materialist.”

I don’t want to ignore this McCarthy—he’s very fun—but I can’t quite get him. There is a sense that this was not the Cormac McCarthy, only the public McCarthy, or the man bound by the strictures of an interview. Surely there was more to his mind than this? I wonder. As a member of the public, it’s not my right to know what he really thought about all these things. Or, maybe this was the real McCarthy. Maybe things are that simple: life is short and fun but hard, and the big answers are just clouds. Even as I’ve struggled with this McCarthy, still I’ve learned from him. Most things are simple, after all. And life, as Wittgenstein rightly taught, is often about becoming content with simple true things, however disappointing they might feel at first.

Then there is the third McCarthy. This McCarthy moved his work from the South to the West, perhaps to escape the shadow of Faulkner. And escape he did, though he took some help from Hemingway along the route. This is the McCarthy of his “Border Trilogy”—All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing, The Cities of the Plain—and No Country for Old Men, The Road, and The Sunset Limited, again with instances throughout his other work, especially his first, The Orchard Keeper, and his last, Stella Maris. Here McCarthy chastened his diction. There are still plenty of run-on sentences, but the words are simpler, and the punctuation marks cut to bare necessity. Yet curiously enough, these novels are filled with exciting plots and characters who let their deepest yearnings erupt. The greatest and most developed protagonist of McCarthy’s work, Billy Parham, roams the American and Mexican Southwest as he loses his family and looks for whatever might be a god or lover or friend. The characters of these novels weep, and we weep with them, as McCarthy indulges in their shared dreams and lost hopes. It frankly seems impossible to cast the writer of these books as ‘pretty much a materialist’—there is just too much material pointing to the opposite. Some have even called this McCarthy gnostic, so spiritual an interpretation do these works beckon. Perhaps the public McCarthy was careful to say only ‘pretty much.’ Once asked by Oprah (of all people) whether he believed in God, he answered, “it would depend on what day you ask me.” This third McCarthy is writing on a very good day.

Somewhat surprisingly, this is also McCarthy at his most delighted at everyday joys. There are many tender passages of drinking coffee in porcelain cups in diners, eating tortillas and beans on stops in the desert, working with cowboys at small jobs on ranches, and companionship with horses, mules, even wolves. He did not leave his love of surfaces behind but deepened it, channeled into everyday intimacies that would help any reader come to love West Texas. No gnostic, he.

And the moments of family. It is well known that The Road is based on McCarthy’s love of his son John, born to him in his old age. But even before that, McCarthy had indulged in both brotherly love (and its loss) and the hope of an ultimate family in the Border Trilogy. At its conclusion, a kindly family took in old Billy Parham. In the last scene, the mother told him that she’ll leave the light on for him and promised he will see his brother Boyd again. “And she patted his hand. Gnarled, ropescarred, speckled from the sun and the years of it. The ropy veins that bound him to his heart. There was map enough for men to read. There God’s plenty of signs and wonders to make a landscape. To make a world.”

Which leads me to the fourth McCarthy. Of course, the three I have just described are not so distinct. Somehow, they (as well as many other McCarthys) did fit together in the the one man as he was, to himself and those close to him. From what I’ve heard, he was quite jovial around those he knew. But I never met him, so I have no right to describe the real man. Hence the fourth McCarthy I have is only who he was to me—perhaps no more than my own construction. He includes the three just mentioned, but perhaps the third most of all, with a heightened sense of hope. He told Oprah, “sometimes it’s good to pray, I don’t think you have to have a clear idea of who or what God is in order to pray. You could even be quite doubtful about the whole business.” It is telling that, in a time when many very smart people were content without praying to God but thought we could use old values and ideas about him, McCarthy thought the opposite: old metaphysics may be gone, but he could still pray. And prayer is not without hope in Someone to Whom he is praying.

So, he is the Billy Parham who finally found a home at the end of The Cities of the Plain. The boy of The Road who kept the fire burning and was adopted into a family in the end. And he is the dreaming Ed Tom Bell who knew he’d meet his father in all that cold and all that dark, and there would be a fire burning when he got there.

But most of all, he is the ex-Mormon, ex-Catholic ex-priest hidden in the middle of The Crossing—my personal favorite—who tells the tale of a man elected by God to survive two earthquakes, even as his family died in both. The man grows old and dwells in the church rubble from which he was once rescued, hoping the rest of it would collapse upon him as he argues against the Providence of God. He debates a local priest of “liberal sentiment” who thinks he sees God in all things and “has love in his heart.” But alas, “He did not. Nor does God whisper through the trees.” Instead, as the man protests,

His voice is not to be mistaken. When men hear it they fall to their knees and their souls are riven and they cry out to Him and there is no fear in them but only that wildness of heart that springs from such longing and they cry out to stay in his presence for they know at once that while godless men may live well enough in their exile those to whom He has spoken can contemplate no life without Him but only darkness and despair. … To see God everywhere is to see Him nowhere. We go from day to day, one day much like the next, and then on a certain day all unannounced we come upon a man or see this man who is perhaps already known to us and is a man like all men but who makes a certain gesture of himself that is like the piling of one’s goods upon an altar & in this gesture we recognize that which is buried in our hearts and is never truly lost to us nor ever can be and it is this moment, you see. This same moment. It is this which we long for and are afraid to seek and which alone can save us.

After weeks of fighting, the old man dies in the priest’s arms, and the priest learns that “in the end we shall all of us be only what we have made of God. For nothing is real save His grace.” And the tale ends, and the ex-priest bids Billy Parham, vaya con Dios, joven.

This is my McCarthy. I read this passage at a time when I felt keenly godforsaken. In that moment I learned, or re-learned, what I longed for. Only a God can save us, as another smart person once said. Cormac McCarthy’s work is full of death, and dreams dashed, and despair, and darkness. But therein is a light—the slightest light, so dim, each flicker giving doubt whether it will hold. But it is there. And it promises salvation. And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness cannot comprehend it.

I confess, I cherish and thank God and pray for this fourth McCarthy, that he be truly so. Who knows? Maybe he is. After all, in the end we shall all of us be only what we have made of God—and that includes Cormac McCarthy who, however obscurely, made a lot of God. For nothing is real save His grace.

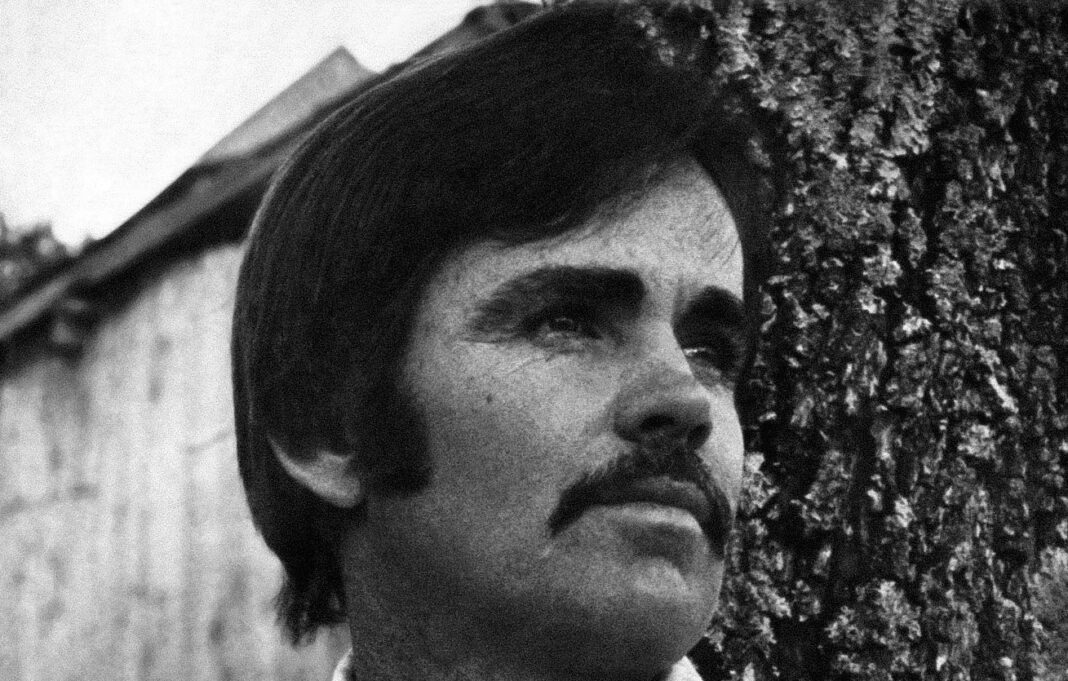

Image credit: “Cormac McCarthy (Child of God author portrait – high-res)” via Wikimedia

A lovely piece, Casey. BTW I’d sure love to know where the barn is that he built outside of Knoxville (being just outside of Knoxville).

Two McCarthy bits: first, from 1989-95 I had my second bookstore on the town square in Knoxville. The TVA towers were just a stone toss away from my doors. Perhaps once a week C.M.’s brother would come in to look around and buy books. Second, three blocks over from Market Square was Annie’s jazz club. That was owned by Cormac’s first wife.

Oh, one more, for those in the know, there was a guessing game on the characters mentioned in Suttree. Because although set earlier, it was said that he drew inspiration from the street people he knew at the time of writing. They walked among us, so it was said. And, also, I should add, thanks to him, I’ll never look at a watermelon field the same way ever, ever, again.

Cheers,

Brian

Brian,

Thank you for the kind words and the stories. Nor can I, regarding the watermelons. I’d expect nothing less. Was there a goatman preacher raising revivals around town back then?

Oops, I think Annie was his second wife. But who is counting. I’d have to refresh my memory of Suttree on goatman. There was a famous street preacher at the corner of Union Avenue and Market Square for as long as I can recall. He came out every day at about 11am and stayed through lunch hour until 1pm. His voice resonated…blocks. Even Jeff, the town square schizophrenic, gave him a wide, albeit admiring, berth. One of my favorite anecdotes about Jeff was this, one day I was walking from my bookstore to the bank and passed Jeff in an empty store front, leaning against the glass, listening. He stepped back from the glass and said in a loud clear voice, “Beware the angels of love.” I was blown away; in another era you would be bringing Jeff a goat as an offering to get love advice.

Cheers,

Brian

Casey, thank you for this piece on Cormac McCarthy, premier writer who lived in (crossed over the border of) two centuries. Well done.

This is the best obituary/memorial I’ve read so far. Elegant and touching. You captured the multiplicity I’ve felt in McCarthy for some time. Thank you!

Loved this piece, made me want to get to the library and pull one of his books I haven’t read yet. Maybe I’ll try Outer Dark.

Comments are closed.