Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home— “Intimations of Immortality,” William Wordsworth

As adults, do we see the age of childhood as being hermetically sealed off from us in our adulthood, something to be looked upon, often with regret, in our more nostalgic moods but, other than that, simply existing as a ‘wreck of loftier years’? Or, like the Romantic poets suggest, are there, in fact, ‘reanimating,’ ‘vivifying,’ ‘breezy,’ ‘fructifying’ forces at work in the disciplined memory of childhood, restorative forces that work with “quickening virtue” and are the “hiding places of man’s power”?

Analogously, for Christians, was everything lost forever in that notorious disaster in the Garden? Or is it true that, in the words of the hermetic — in a different sense of the word — Leon Bloy, (1846-1914) the French Catholic writer, whom Pope Francis quoted in his first homily as pope:

By means of the Immaculate Conception, God was able to place his foot upon earth. Here is the sole door through which He was able to escape from the Garden of Delight which is his Mother and whom a thousand centuries of blessedness could not enable us to understand.

… all the same there remained preserved a drop of divine Sap, [emphasis mine] just enough to save billions of worlds; and that in the end there blossomed that Flower more beautiful than Innocence. which Christians name, understanding nothing about it, the Immaculate Conception, Mary herself, the sublime Garden regained.

One more question: Am I wrong to direct people to the third chapter of Christopher Lasch’s The True and Only Heaven as perhaps the best place to go to read about the theology of the Immaculate Conception?

Let me explain.

In the brilliant Chapter Three of The True and Only Heaven, “Nostalgia: The Abdication of Memory,” Lasch puts forth a analysis of the distinction between memory and nostalgia. Because the increasing rate of transformation of society this distinction gained relevance during the 18th and 19th centuries, which saw both the Romantic movement as well as the promulgation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception (Leon Bloy, in fact, goes out of his way to say we could not “understand” it until a certain time). Finding analogies in the temporal frameworks of the life of an individual, the history of the West and the history of the United States as well as the spacial framework of town and country, Lasch pinpointed a weakness and corruption when individuals and cultures abdicated the discipline of memory for its cheap substitute, nostalgia.

In simple terms, memory is the disciplined use of the past when it has a connecting thread, (or, to use a more organic metaphor associated with, strength, continuity and growth: sap), with the present. In contrast, nostalgia is the rejection of the present for an imagined past. It’s a hapless and sapless recollection that Lasch said is actually a way of “dismissing the past.” He elaborated on the difference as follows:

Just as we should reject the thoughtless equation of progress and hope, so we need to distinguish between nostalgia and the reassuring memory of happy times, which serves to link the present to the past and to provide a sense of continuity. The emotional appeal of happy memories does not depend on disparagement of the present, the hallmark of the nostalgic attitude. Nostalgia appeals to the feeling that the past offered delights no longer obtainable. Nostalgic representations of the past evoke a time irretrievably lost and for that reason timeless and unchanging. Strictly speaking, nostalgia does not entail the exercise of memory at all, since the past it idealizes stands outside time, frozen in unchanging perfection. Memory too may idealize the past, but not in order to condemn the present. It draws hope and comfort from the past in order to enrich the present and to face what comes with good cheer. It sees past, present, and future as continuous. It is less concerned with loss than with our continuing indebtedness to a past the formative influence of which lives on in our patterns of speech, our gestures, our standards of honor, our expectations, our basic disposition toward the world around us.

Lasch was at his best in that chapter when he invoked the Romantics poets Wordsworth and Coleridge for their insights into this difference. Wordsworth:

Memory:

Whereby this infant sensibility

Great birthright of our being, was in me

Augmented and sustained.

Nostalgia:

And custom like upon thee with a weight,

Heavy as front, deep almost as life.

And he cited Coleridge’s prose to make the case that both those who see the past as only a time they were imposed up and those see it solely as a time of “blissful innocence untroubled by self-conscious reflection,” were guilty of the nostalgic mode of reflection in that, “they are not good and wise enough to contemplate the past in the present” (Coleridge). The proclamation of pure and “divine sap” or “trailing clouds of glory” that miraculously rise, undefiled, up through the dirty ages of time and blossoms forth at it’s proper time, however, has elements of both.

O joy! That in our embers

Is something that doth live.

That nature yet remembers

What was so fugitive.

And we are indebted, says Lasch, to contemplation of both the dirty and the pure, the fallenness and the innocence. Father forgive me, I am both an Augustinian and a Pelagian!

I think all of this is highly important as I’m convinced productive and unproductive forms of conservatism can be discerned and diagnosed using not much more than this analysis plus the virtue of gratitude (indebtedness) which, according to Lasch, was the “dominant emotion” in Wordsworth poetic work in this vein and which Cicero called the greatest and parent of all the virtues. This also seems more than congruous with Pope Francis’ own address this month on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception: “Faced with the love, faced with the mercy and the divine grace that has been poured into our hearts, we have one single duty: gratitude.”

While doing a good job at skewering a false and unproductive form of progressivism in his closing address at the Synod on the Family (“The temptation to a destructive tendency to goodness that in the name of a deceptive mercy binds the wounds without first curing them and treating them; that treats the symptoms and not the causes and the roots. It is the temptation of the “do-gooders,” of the fearful, and also of the so-called “progressives and liberals.”), Pope Francis also highlighted the conservative temptation to nostalgia: “a temptation to hostile inflexibility, that is, wanting to close oneself within the written word, (the letter) and not allowing oneself to be surprised by God, by the God of surprises, (the spirit); within the law, within the certitude of what we know and not of what we still need to learn and to achieve.”

To quote the “About” section of this website, “We’re in a bad way.” And in order to search for Wordsworth’s “hiding places of man’s power” — in other words, to do something about it — I think it more than worthwhile to add the spiritual to Lasch’s brilliant merging of the poetic and the political. After all, there’s a sort of Porcher Manifesto, (more commonly known as the Magnificat) that brings all three together in great power, and it was sung by Mary, the Immaculate Conception.

My soul glorifies the Lord, *

my spirit rejoices in God, my Saviour.

He looks on his servant in her lowliness; *

henceforth all ages will call me blessed.

The Almighty works marvels for me. *

Holy his name!

His mercy is from age to age, *

on those who fear him.

He puts forth his arm in strength *

and scatters the proud-hearted.

He casts the mighty from their thrones *

and raises the lowly.

He fills the starving with good things, *

sends the rich away empty.

He protects Israel, his servant, *

remembering his mercy,

the mercy promised to our fathers, *

to Abraham and his sons for ever.

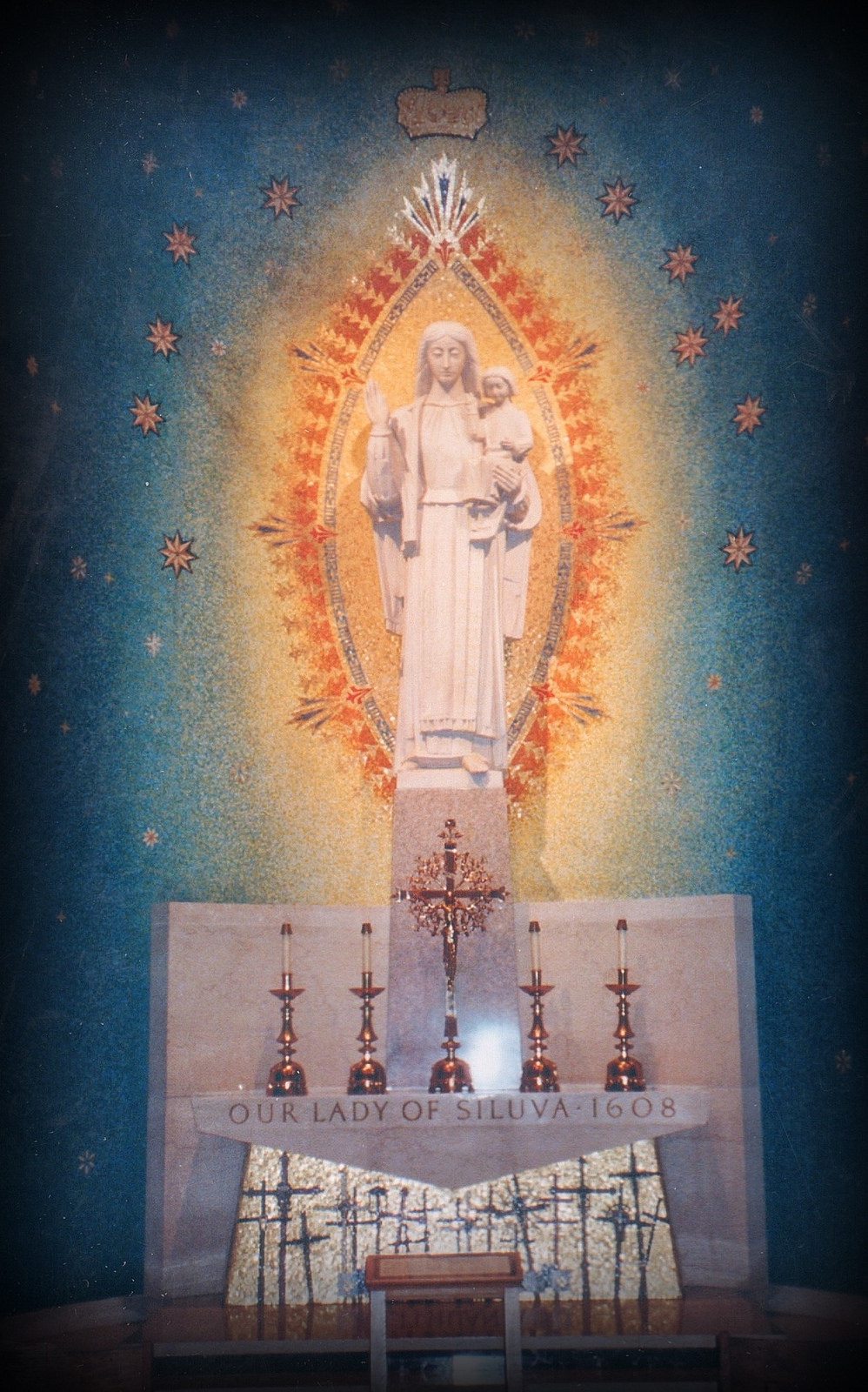

(Image source)