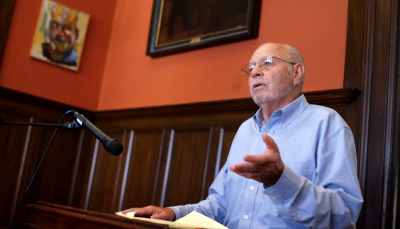

Paul Gottfried is among the most important contemporary conservative thinkers. An intellectual historian, since the 1980s Gottfried has been the foremost critic of American conservatism from the perspective of someone inside the movement. He later founded organizations that reflected these criticisms.

Gottfried entered the conservative movement at the tail end of the New Right’s influence and just as the neoconservatives and Protestant Evangelicals were gaining traction. His two greatest contributions to conservatism—if I may limit it to that number—are his reintroduction of historicism as a viable way to approach conservatism, and his profound critique of conservatism which begins with his 1986 book The Search for Historical Meaning: Hegel and the Postwar American Right.

Ten things about Gottfried’s career and life that are worth knowing:

- Paul Gottfried is a practicing Jew with deep affinities for “Reformation Protestantism.”

- He is a historicist, but not a Hegelian.

- He no longer goes by the label of conservative. Instead, he uses more specified terms like reactionary, right-winger, and right-wing pluralist to describe his views.

- He has written what is known as the Marxism Trilogy, a kind of rejoinder and addition to Christopher Lasch’s populist narrative against progress.

- Gottfried and Lasch struck up a friendship through participation with the Telos group.

- He held a position in the same Humanities Division at Michigan State that Russell Kirk once occupied.

- He invented the term paleoconservative.

- He was a supporter of M. E. (Mel) Bradford during the famed NEH dispute.

- He studied with Herbert Marcuse during Marcuse’s short stay at Yale.

- Gottfried can read an impressive ten languages and speak four of them with proficiency. Besides English, he publishes in German and French.

So how is it that the name of Paul Gottfried has not garnered the same attention of the likes of Russell Kirk, Robert Nisbet, and Leo Strauss?

There are several reasons, including the timing of his entrance into conservatism and the fact that most of his books are monographs aimed at other scholars (although the same could be said for much of what Nisbet and Strauss wrote too). However, there is a more profound reason, one illustrated by a snippet of dialogue from the film The Departed. The characters Billy Costigan and crime boss Frank Costello discuss Costigan’s deceased father and Billy asks if his father ever dipped into criminality. Costello says that Billy’s father kept his own counsel and never desired wealth; “You can’t do anything with a man like that,” Costello retorts. The same might be said for Gottfried, who has shunned popularity in return for loyalty to a conservatism rooted in the historical imagination.

Gottfried published his first book in 1979, but it was not until 1986 the he took direct aim at conservative thinking. In The Search for Historical Meaning (TSHM), Gottfried claimed that the seeds of the eventual neoconservative takeover of the conservative movement were embedded in the first generation of the postwar New Right. The majority of the New Right chose not to openly embrace the idea of historicism because of its association with fascism and Nazi Germany. Historicism—an idea that represents continuity for Gottfried—would have allowed conservatives to keep that movement politically and ideologically small (national, regional and local) without having to borrow from the universal language of Enlightenment Liberalism that fronts the administrative state.

The language and apparatus of a true conservatism, Gottfried believes, should be regionally and historically defined. Even universalizing or Americanizing the Burkean principles of custom and prescription (etc) are eventually self-defeating for the reasons that conservatism was never meant to be global like liberalism. The themes found in TSHM are the ones Gottfried fleshes out in various ways throughout his career. As the influence of neoconservatism has grown, Gottfried has dedicated more ink to the links between neoconservatism, Leo Strauss and the Straussians, and anti-historical conservatism.

It is necessary to historicize Gottfried in order to understand the nature of his criticisms. He became friends with Russell Kirk during his one-year stay at Michigan State, and he came to know other New Rightists like Frank Meyer. The importance of this fact cannot be ignored, for the New Right and its ideas were already in decline in the 1960s and 70s. Despite Gottfried’s Jewish heritage and upbringing in the Northeast, and the fact that he was educated at an Ivy League institution, he never joined forces with the neoconservatives. In Gottfried’s autobiographical account of his life and career, the conservatives (or reactionaries) he applauds are Christopher Lasch, Eugene Genovese, Peter Stanlis, Robert Nisbet, and Mel Bradford.

Besides The Search for Historical Meaning, Gottfried wrote the Marxism Trilogy, a prolonged intellectual genealogy of liberalism and Marxism. In After Liberalism (1999), Multiculturalism and the Politics of Guilt (2002) and The Strange Death of Marxism (2005) Gottfried makes his most seminal contribution to the field of intellectual history. His running thesis is that American liberals (and progressives in general) radicalized Marxism and exported it back to Europe and not the other way around, as the story is generally conveyed. Another trope that follows from the trilogy is Gottfried’s belief that America is not an inherently conservative nation (a claim made prominent by a few postwar conservatives), but one with long roots in a progressive tradition.

Gottfried’s career in conservatism has been anything but boring. He was a central player in the conservative civil war(s), as Daniel McCarthy refers to them. He supported Bradford for the chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1981, and sided with the traditionalists during the debates at The Philadelphia Society. Eventually, Gottfried found himself persona non grata as his participation in the organizations that once welcomed him became impossible thanks to his unrelenting denunciations of neoconservatives, the Republican Party, Straussians, and the sources of funding they dominated. In the last several years, Gottfried has been busy as the founder of The (H.L.) Mencken Club, which meets annually in Baltimore.

A Few Links:

The Search for Historical Meaning: Hegel and the Postwar American Right (Northern Illinois University Press, c1986, 2010).

The Marxism Trilogy

After Liberalism: mass democracy in the managerial state (Princeton University Press, 1999).

Multiculturalism and the Politics of Guilt: toward a secular theocracy (Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press, 2002).

The Strange death of Marxism: the European left in the new millennium (Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press, 2005).

American Conservatism, Neoconservatism, and Leo Strauss

Conservatism in America: making sense of the American Right (New York: Palgrave, 2007).

Leo Strauss and the Conservative Movement in America: a critical appraisal (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Organizations

Seth Bartee is a doctoral candidate at Virginia Tech. His dissertation is a consideration of how certain American conservative intellectuals created imaginative counter-narratives to the liberal consensus tradition.

Gottfried’s steady rebuke of the Brain-Eating virus of neo-conservativism should be appreciated by all.

Thanks for calling our attention to Gottfried. He’s written some great things over the years.

I was not familiar with Gottfried until I ran across a recent article he wrote in Radix, where he mentions being “purged” recently from ISI for his leadership role in the HL Mencken Club and association “with people who stress hereditary cognitive differences.” After looking at the rest of Radix, its leadership, associates, financial supporters, and the comments it allows, I would call it quite plainly the mouthpiece of a racist white nationalist publication that is aptly identified in the media as a hate group. These descriptions seem to be accepted by many of the “alt-right,” “neo-racialist” principals.

Does FPR have a response to this? I say it’s way over the line.

We unequivocally denounce the Mencken Club’s position on race. And, while we admire much of what Mencken himself wrote, we also distance ourselves from a great many of his ideas.

Do you have any substantive criticisms of what Prof. Gottfried wrote there?

Comments are closed.