[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

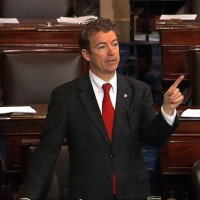

Senator Rand Paul’s filibuster of the nomination of John Brennan to be head of the CIA–something that he did in order to “draw attention to deep concern on both sides of the political aisle about the administration’s use of unmanned aerial drones in its fight against terrorists and whether the government would ever use them in the United States”–came to an end just after midnight on Thursday. I disagree with probably over 3/4’s of everything Paul claims to believe: I think his libertarian ideology is fundamentally flawed, I think this reading of American Constitutional history his deeply misinformed, and I think his distrust of the federal government is grounded more in paranoia and (whether he realizes it or not) a fetishization of property and states rights than anything chastened or wise. All that being said, Paul was the wise person in the U.S. Senate last night, and as someone who ends up (while often holding his nose) voting for far more Democrats that Republicans, I found it outright embarrassing that, aside from a couple of brief supporting comments from Democratic Senators Ron Wyden and Dick Durbin, Paul’s only allies all yesterday afternoon and evening were on the Republican side of the aisle, and rather marginal and dim Republicans at that (seriously…Mike Lee?). So many strong Democrats that were attentive to and tried to protest against the civil rights abuses inherent in the Patriot Act and the Bush administration’s expansion of the government’s war-making powers sat on their hands. Supporting one’s own President (or America’s quasi-imperial foreign policy agenda) trumps all, I guess.

But I suppose that isn’t actually surprising, because supporting the nominees of one’s President, and trusting in the technological and legal enabling of our expansive War-on-Terror global apparatus is just business as usual for both Republican and Democratic members of the political class, is it not? The Senate is a ridiculously dysfunctional institution, one which regularly defaults in favor of the business-friendly establishment, but when all is said and done it knows what it wants, and the whole reason Paul went through with this old-school, grand-standing filibuster (which basically never happens any more) was in part because the “majority seemed unfazed by giving up the day to Paul’s filibuster“; Brennan’s nomination, in other words, like the administration’s continued reliance upon drones, is basically already in the bag. And much of the news coming out of Afghanistan is moderately positive these days; isn’t it likely that a good deal of that increase in security is the result of the Obama administration’s aggressive waging of a nearly cost-free (for American soldiers, that is), drone war–made possible thanks to highly invasive, high-tech intelligence operations, of course–in the mountains of Pakistan? Who wants to get in the way of a war which is, at long last, both winding down and coming up with defensible results? And besides, isn’t it simply a given that the President of the United States ought to be able to wield these kind of powers? The Constitution explicitly gives the president broad power defend the United States in the face of all sorts of “insurrections” and “conspiracies,” doesn’t it? (Well, actually, maybe that was the Insurrection Act which does that…or maybe it was the 2007 amendments to the Act…of course those amendments were later repealed…and anyway, there’s the strict guidelines of the War Powers Resolution over there, the actual law of the land, but drones are perhaps not actually “armed forces,” as specified in the law, so we can probably just continue to ignore it, as every president, both Democrat and Republican, has since it was passed over Nixon’s veto.)

In the end, no doubt Senator Lindsey Graham spoke correctly–the only people who are worried about Obama’s use of drone warfare and terrorist-assassination, which is clearly only an extension of Bush’s prior building up of the president’s war-making power, are libertarians and the left. Well, actually, no, let’s that amend statement a bit–localists are opposed to it too. But we know who aren’t: liberals.

By liberals, I’m not talking about the Democratic party, or any particular subset of it. I’m not talking about those often referred to as “progressives,” since their concerns about civil liberties and economic justice are ones I’m often in sympathy with. No, I’m talking about all the folks who, because they prioritize individual rights in the usual juridical way, basically are primarily concerned about making sure that the economic-freedom-and-equal-rights-protecting modern liberal technological order keeps operating smoothly. As was famously noted by Alasdair MacIntyre, “contemporary debates within modern political systems are almost exclusively between conservative liberals, liberal liberals, and radical liberals.” Democrats and Republicans alike–indeed, pretty much the entire mainstream of political opinion in the United States, it sometimes seems–fits under this label. Some want more money spent here, some want less money taxed there, but they all are basically in agreement upon the same project: a powerful and opportunity-guaranteeing and well-defended state, which will pragmatically take care of all the messy business of maintaining one’s wealth and position in a diverse and dangerous world…without bothering too much with requiring the citizens themselves to take charge. This utilitarianism, and its consequent reliance upon technology and the marketplace and bureaucracy, has been part of the American order from the beginning, despite the dissident voices ranging from the Anti-Federalists in the 18th century, the Populists in the 19th, and the New Left in the 20th. By this standard of measurement, the demand which Senator Paul was making of President Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder–that they put in writing their commitment to never make use of the immense and deadly power which drone technology makes available to the President either against an American citizen or U.S. soil, at least not with the formal due process of law–was really a bridge to far. Drone warfare is working, after all! Don’t you want the liberal (and by now, quasi-imperial) American project to work?

Well, I can speak for the left, sort of: no, not necessarily, not any more than we automatically want any state project to work, not when it is as susceptible as America’s has been to the un-equalizing economic forces of globalized capital and the corporate marketplace. Drone warfare is just one more element in a depersonalizing and thus profoundly undemocratic process, which takes more and more equalizing authority away from the people or their representatives and puts it in the hands of those in power–and, thus, those economic agents who profit most from writing the rules of the democratic game so as to keep them there. I can, perhaps, speak for localists too, though there my cred is probably somewhat less: no, again not necessarily, not at least if the project in question is implicitly a centralizing and cosmopolitan one, making use of political authority to wage wars (and greater or lesser cost, in both lives and money) in distant lands for ideological (or corporate-driven economic) causes, obliging the economies and the family patterns and the social norms of communities to be subservient to priorities which they had no real part in choosing.

And the libertarians? I confess my suspicions there. There are, to be sure, many thoughtful people who associate themselves with that label, and do so in ways which focus on exactly the sort community-destroying, democracy-undermining government and business collaboration and centralization which localists and leftists generally oppose. But I look at Senator Paul, and it seems to me that, on the basis of what he’s gone on the record saying before, that his is the unfortunately too-common neo-Confederate style of libertarianism, where the central issue is not so much democracy or even civil liberties but rather my rights–that is, keeping other people away from my stuff, my rights, my property, at all costs. That’s no way to organize a decent society, in my opinion. Part of me suspects that Rand Paul-style libertarianism might be perfectly okay with drone warfare, even he was assured that the only folks that would ever be taken out by the president would be Hugo-Chavez-style strongmen who threaten America’s influence over oil markets.

But that’s probably unfair. The fact of the matter is, whatever the true nature(s) of the Tea Party movement which help put him in the Senate, Rand Paul yesterday stood up for a principle that I think needs standing up for–and if the libertarian argument motivated him to say something which any good leftist reader of The Nation or any good localist reader of Front Porch Republic would agree with, good for him. Drone technology, like nearly any technology–as thinkers from Wendell Berry to George Grant to Martin Heidegger have taught us–has the ability to distract us, to mask the real world from us, to everything (even human lives) into tools and checkboxes on a list. Philosophical liberals, generally speaking, just don’t see this, because their notion of individuality depends, to a great extent, on just always making maximum use of the best, most cost-effective, most efficient, least demanding tools possible. That’s a sad reality, and not one easy to change (especially since most us, working on our laptops and living lives in which terrorist cells and the mountains of Pakistan are fortunately just abstract notions, really kind of like tools which enable us to not bother with such things). Senator Paul didn’t change any of that yesterday, but he made it clear that he was someone–whether he realized it or not (my guess is he doesn’t, at least not fully)–who was willing to contemplate, via putting down some absolute limits on the president, some real change in the way things are supposed work in the liberal order to day. May his tribe (well, actually, not really, but still: the tribe of differently-thinking people who agree with him on this crucial point) increase.

“someone–whether he realized it or not (my guess is he doesn’t, at least not fully)–who was willing to contemplate, via putting down some absolute limits on the president, some real change in the way things are supposed work in the liberal order to day.”

This line is truly bizarre, especially from someone who provides a couple of links that demonstrate you’re at least passingly familiar with the Paul family. They may both be cranks (unlike his dad, I suspect Rand is smart enough to lie about his truly politically poisonous positions, much like our current president), but in the area you’ve mentioned they’ve both always been 100% consistent from everything I’ve ever seen.

Brian,

This line is truly bizarre….in the area you’ve mentioned they’ve both always been 100% consistent from everything I’ve ever seen.

A couple of friends of mine have pushed me on this point, saying that Rand Paul, like his dad, have always been entirely consistent when it comes to civil liberties and executive power, so I blame myself for not being clear enough. The line you quote follows my final observations about technology and modernity–namely, the simple fact that the modern democratic and economic order is one which heavily relies upon technological tools, and that if you support that order–one which allows us and so many other so many liberal freedoms–than you kind of have to take seriously the best tools available for achieving it. And really, drones are great tools for warmaking. (Cheap, effective, and deadly.) I think Paul really does fully understand and appreciate the costs of giving the President of the United States these kind of warmaking powers; I am doubtful that he’s a Wendell Berry reader, who is conscious about how our whole socio-economic order makes it almost impossible for us not to want to build and rely upon the best, most effective, most easily-outsourced killing tools money can buy. (I know that Paul has spoken against using drones on American citizens or on American soil; I’m unaware of him speaking against drone warfare itself. If he has, I’m ready to correct myself.)

Fantastic article. Well done.

Mr. Fox–You speak my mind pretty thoroughly, and even when writing at what looks like white heat (hence all the subject-verb agreement fluffs, the missing words, etc.–but by golly, your spelling’s terrific), which I could never do. I, too, was glad that Paul did what he did, though I suspect his motives are ultimately ignoble–let’s call them consumer-libertarian, perhaps.

Ray, I was about to get huffy with you and insist that I didn’t have any missing words, but in quickly scanning the post I just discovered two, plus a couple of errors, so I’m just going to quietly eat crow in a corner, thanks. (I like your description of Paul as a “consumer-libertarian”; that works, I think.)

“I think this reading of American Constitutional history his deeply misinformed, and I think his distrust of the federal government is grounded more in paranoia and (whether he realizes it or not) a fetishization of property and states rights than anything chastened or wise”

So someone who writes for a website that celebrates localism (“place, limits”) has a problem with states rights? And exactly what “reading of American Constitutional history” do you champion? The “living, breathing” reading?

I noticed even before the presidential election of 2008 that there was a point where the Far Left and the Far Right merged and became one, though partisans on both sides get inflamed at the thought. Rand Paul was, of course, quite right and the absence of Democrats in Washington supporting him was shameful. There were, however, a great number of us out here giving him virtual fist bumps.

Mr. Phillips,

The term “states’ rights” is a not so subtle code for “Southern racism.” The term “states rights” is also an unfortunate post-bellum term which implies that if the states have any rights at all, they have them from, well, the fictional aggregate of the “American people” or from the general government which masquerades with the usurped title of “federal government” when it is in fact naught but the naked Hobbesian state. Historically accurate, as our good friend, Don Livingston, among others has established “beyond” reasonable doubt, is “state sovereignty” in the context of historical subsidiarity, realizing that the “state” in that context is not the bureaucracy of the executive, legislative or judiciary of a given territory, but it is the people thereof with their traditions, their customs, their habits, their taboos, their virtues, their vices and their hopes. One should always be skeptical of the notion of “rights,” which in the modern understanding are artificial constructs of modernity, things floating in the ether to be “discovered” as emanations in a penumbra, whether the term be applied to a state, an individual or some ideal of “localism.”

Mr. Peters, I would expect the readers of Daily Kos or Democratic Underground to assume states’ rights is code for Southern racism. I would not expect the readers or writers at FPR to assume that. Rather, I would expect them to assume it means such things as enumerated powers at the federal level, nullification, interposition, and secession. That said, what objection to the concept of states’ rights would a localist have?

I get your semantic concerns with the use of the word rights, and I actually usually try to avoid the use of the word except when the context is clear (2nd amendment rights for example). I assumed that the use of the historical term states rights was one of those times when the context was clear.

I’m still not clear what alternative “reading of American Constitutional history” RAF is proposing. One can criticize philosophical libertarianism or even “neo-Confederate style of libertarianism,” but that doesn’t make their reading of American Constitutional history incorrect. The Constitution does not mean what RAF would like it to mean or even what Rand Paul would like it to mean. It means what the people who wrote it intended and the people who ratified it thought they were getting, and I believe the “neo-Confederates” get that pretty much right. Of course this reflects my originalist assumptions. Perhaps RAF is not an originalist.

Red,

To combine a couple of your comments together…

Someone who writes for a website that celebrates localism (“place, limits”) has a problem with states rights? What “reading of American Constitutional history” do you champion? The “living, breathing” reading?…I would [instead] expect them to assume it means such things as enumerated powers at the federal level, nullification, interposition, and secession. That said, what objection to the concept of states’ rights would a localist have?…The Constitution does not mean what RAF would like it to mean or even what Rand Paul would like it to mean. It means what the people who wrote it intended and the people who ratified it thought they were getting, and I believe the “neo-Confederates” get that pretty much right. Of course this reflects my originalist assumptions. Perhaps RAF is not an originalist.

Your comments both sketch out your own position well, and also diagnose at least part of my own. Unlike you, I’m not an originalist in my approach to the Constitution. The fact is, I’m not even much of a constitutionalist in general, since it seems to me to be the experience of nations around the world that a strict reverence for any historically defined reading of a specific constitution tends mainly to empower one group who is able to use their historically contingent position of privilege to maintain that position long after the popular justification for it has evaporated. If we must have a constitution, then I would prefer to read our Constitution in exactly the way you suggest–as a living document. I don’t know how we can most effectively ensure the continued growth, adaptation, equal treatment, and thus continued relevance of communities otherwise. Those who read the 10th Amendment to the Constitution as a license for interposition and nullification–like John C. Calhoun and others–were not, I think, actually defending the “communities” of South Carolina, etc.; they were defending a particular class and a particular set of interests in a specific segment of the polity. Thus, as a localists and a communitarian on the left–some who, like Christopher Lasch and others, strongly believed that you needed to continually change and adjust governing policies to ensure that economic and political power is not aligned against the survival of families and communities–I’m quite suspicious of attempts to challenge the unequal concentration of power in “neo-Confederate” Constitutional terms, because that model holds up a way of thinking about local power which makes use of what strikes me as a bankrupt history.

Some of my friends have actually challenged my support for Senator Paul on this basis–that I’m giving too much credit to Paul, that he’s actually just another secessionist in disguise. That may be, but I’ve gotten to know (mainly through this website!) enough intelligent and community-respecting libertarians that I want to give them the benefit of the doubt. Paul was doing the right thing on Wednesday afternoon, even if it was the case that his filibuster was more about grandstanding than making any actual changes. (Though Attorney General Holder did, in response to Paul’s filibuster, at least issue a specific statement that the President does not have the power to arbitrarily use his warmaking powers in the United States; that has to count for something!) As such, neo-Confederate originalist or not, I salute him. It doesn’t change my mind about how he’s viewed the debate over national power in the fast (attacking the Civil Rights Act of 1964 because of the way it infringed upon (white) people’s property is a bit of a give-away), but strange times make for strange bedfellows.

I have to confess this is all a lot of “meh,” in my humble opinion. If I were a senator, I wouldn’t want to associate myself with Senator Paul’s objections, and I certainly don’t blame any of them for acting likewise.

Paul’s complaints were simply bizarre, and his proposed solution even more so.

First, why does he limit his concerns to drones? Presidents have numerous tools in their box–bombs, snipers, poison, rogue Green Berets, etc.–by which to remove citizens that have grown annoying. Why is he only talking about drones?

Second, he conjures an America where a Hitler-figure (yes, he goes there) blasts citizens sitting in cafes and takes down war critics such as Jane Fonda. Now there’s a real-world concern if I’ve ever seen one.

Third, having conjured an administration bristling with Predators and Hellfires, led by a big-government tyrant who “shreds the Constitution” (his words) and who clearly has no love for America or respect for fair play or civil liberties or presumably mom or apple pie (sweet-potato pie’s probably more his style), but who does enjoy wreaking havoc (hmm, now who’s fantasies about what public figure might Paul’s picture fit to a “t”?), he suddenly turns around the next day and pronounces himself absolutely satisfied with . . . wait for it . . . a written assurance (what James Madison derided as a “parchment barrier”) from the attorney general.

Translation:

Paul: “You’re a murderous fascist that will stop at nothing.”

Holder: “Not so.”

Paul: “Oh, OK.”

And what does Holder actually say?

“’Does the President have the authority to use a weaponized drone to kill an American not engaged in combat on American soil?’ The answer to that question is no.”

And exactly what is being denied here? Does anyone who’s seen what “imminent” and “battlefield” mean these days in Yemen think “engaged in combat” in the US isn’t going to be construed with some . . . what shall we call it? . . . creative latitude?

Holder’s response was to flick Paul off his sleeve. And rightly so. Of course the president–any president–is going to use deadly force against a serious threat to national security wherever it is found, and whoever it is. It’s far more likely that, in the US, the individual will be apprehended, but in the unlikely event that that’s not possible, they’ll be taken out, just like a SWAT team will take out a criminal.

So, what do you call it when someone believes this power is certain to be abused and used against the administration’s critics, but who is satisfied with a note from said administration to the effect that, “no, we won’t do that”?

I see two options: 1) Senator Paul isn’t very bright. 2) He’s nailing down Tea Party support for a run in 2016.

Mr. Haas, Rand Paul is an ophthalmologist. Opthamology residencies are VERY competitve. Even if we assume that having a Congressman for a father gave him some competitive advantage, you can rest assured that Rand is no dummy.

Also, Holder did not “flick Paul off his sleeve.” The White House clearly blinked. I interpreted the terseness of the reply as childish passive agressiveness. “You forced me to reply, but I’m only going to give you the satisfiction of the bare minimum.” That said, while the answer is an improvement over the previous evasions, the key wiggle term is still “combat.”

Dr. Fox, thanks for the honesty. It didn’t realize you self -identified as “on the left.” Truth be told, I’m not really a Constitutionalist either. I’m an anti-Federalist. But strict reading of the Constitution surely gets us closer to anti-Federalism than the current state of affairs.

But I’m still puzzled at how someone could be a localist and think “secessionist” is a pejorative. If we agree that the current Fed Gov is a monstrosity, and if we agree that the US is too large and therefore ungovernable on the human scale, how do we then get to localism? Is localism only allowed within the framework of the current system? Is devolution OK but territorial secession a bridge too far? This strikes me as PC squemishness. “Heaven forbid I be associated with any of those thought criminal secessionist, lest someone think I have stray un-PC thoughts.”

And history is not “bankrupt.” A particular telling of history is either accurate or inaccurate or some combination of both. If the neo-Confederate history is actually accurate, then it should be dealt with forthrightly, not hand-waved away on the grounds that it offends modern PC sensibilities.

Mr. Phillips, I’m afraid your keenly felt desire to see the White House spanked over this issue has gotten the better of your judgment.

When Holder wrote that the president does not “have the authority to use a weaponized drone to kill an American not engaged in combat on U.S. soil,” he was merely restating what he had said earlier, that “it is possible, I suppose, to imagine an extraordinary circumstance in which it would be necessary and appropriate under the Constitution and applicable laws of the United States for the president to authorize the military to use lethal force within the territory of the United States.”

What Paul did, during his filibuster, was expose his tin-foil-hat-ism (whether sincere or a politically motivated posture–I suspect the latter), with his fantasies of the president targeting Jane Fonda with a Hellfire missile.

If I were Holder, I suspect I would be experiencing something between amusement and disgust at such nonsense, and would want to limit my exposure to its source (even epistolary exposure) as much as possible. Hence, the terseness of the reply.

Subsidiarity, anyone? Or perhaps a dim recollection of Habeas corpus, breezily dispensed with during the Bush II years.

The basic civil rights of every citizen should not be lumped into the arbitrage of contemporary wooly headed thinking. Nor, should this wooly headed thinking bleed out into bonafide military concerns, as it is now doing.

Mr. Haas, if the White House didn’t want to allow themselves some wiggle room then why did they hem and haw and not just give a straight answer? You can’t read the Holder and Brennan statements and not recognize that they are avoiding a straightforward no. As I said, the issue is still the use of the word “combat.” By considering terrorists as irregular “enemy combatants” in the War on Terror, they can use the Law of War and avoid the normal legal process. That’s what this is really about. The ability of the President to designate someone a terrorist and therefore avoid such pesky things as evidence and trials.

@John Haas

I have thought a lot about drone warfare over the years and the threats it poses both at home and abroad. I actually agree with the author on this issue and I have come to see drones as a unique danger to liberty which is very much *unlike* a sniper or a death squad in the amount of terror a small group of military folks can do.

The dirty little secret of any strong government is that the power of that government is not wielded by those who have it in name but by those who carry out the day to day decisions. Since you bring up Hitler, he is a great case in point as he tried, quite unsuccessfully, to fire Himmler near the end of the war (Doenitz, Hitler’s successor, in fact *did* succeed n firing Himmler when he took office but that’s another story). I think this shows the extent to which we mythologize the absolute power we assume dictatorships have.

I remember further reading reports here in the US of air force personnel who disobeyed orders on September 11, after the planes had hit the towers and the Pentagon, to open fire on civilian aircraft which had not landed in a timely manner. These pilots knew what was at stake but they chose *not* to kill civilians here but rather to wait and see, and their reactions were ultimately vindicated.

But one person can only fly one F-22 at a time. Drone pilots can control several at once. This puts a drone pilot in a command and control role over operations in a way that a fighter pilot is not. The drone pilot gets to give the order to shoot but there is no individual with his hand on the trigger there in person who gets to say “no I won’t.” The power is thus the power of a low-level officer but without the checks and balances of the actual triggermen having any discretion as to whether to carry out a given attack order or not. Worse still, the level of attention a drone pilot can give to the actual circumstances is far less because his attention is divided.

What this means, in essence, is that it takes far fewer bad apples to create an environment where the lethal power of the military is directed in places it shouldn’t, and where the level of individualized assessment that can realistically be expected is curtailed as well, and if we have a wise Augustus as Pater Patria today, then what happens when we get a Nero or a Caligula? Drones are such of a manpower multiplier that the ability to control such a leader by assuming that our brave men and women of the armed forces would simply refuse to go along no longer seems wise.

@Mr Peters;

I am somewhat suspicious of rights rhetoric generally (unless we treat rights as contextual and arising from a cultural stream through history), but I don’t see states rights as *necessarily* racist. I will grant you that “federalism” and “states rights” are very often times brought up in such contexts, but the fact is that they are a part of the debate in the other side as well. For example many people I know on the left are hoping for a constitutional crisis over states being required by popular initiative to engage in conspiracies to break federal narcotics laws. There is an open question over states rights here and whether, say, the controlled substances act, can indeed be used to criminalize a state licensing marijuana growers or distributors (recent Supreme Court lineups suggest that, no, the federal government cannot penalize states or state agents for breaking mere commerce clause legislation, see Coleman v. Maryland Court of Appeals, which was 5-4 that the medical leave provisions of the Family and Medical Leave Act was a commerce clause law not applied to the states, but 7-2 that commerce clause laws could not directly bind the states).

So the fact is, everyone is for states rights, except when they aren’t. This is in fact as true on the left as it is on the right.

Mr. Travers, thanks for those thoughts. I confess I’d never thought about the matter from that particular angle before.

Mr. Phillips, you are exactly right. Of course Holder was saying–and still is saying–that there are very unlikely, currently unforeseen, highly hypothetical circumstances where a president would be duty-bound to order the killing of an American on American soil. What those circumstances might be is impossible to say, due to their very unlikely, currently unforeseen, highly hypothetical nature. So, yes, you are correct, Holder was and is avoiding a straightforward “no” answer. (That was my point above.)

So, “why did they hem and haw and not just give a straight answer?” If by that you mean, why didn’t they just say “Yes, the president reserves the right to kill American citizens on American soil without a trial,” it’s obviously because, while that is true, it’s so hypothetical and remote that merely to say it without qualification, as if one were saying, “the president reserves the right to issue signing statements with legislation” actually misrepresents the case, making it seem as if, having acknowledged that this very remote possibility exists at all means the president will soon be incorporating it into his everyday repetoire of activities. That he is not going to do that is as important a part of the answer as that the hypothetical situation might actually someday be realized, and one’s answer, if it is honest, needs to reflect that.

Try doing that without hemming and hawing.

Imagine you’re watching “Men In Black II” with your wife, and she pauses it and turns to you and asks, “So hon, if alien space bugs killed me and took over my body and were using it to do nasty things and destroy humanity, what would you do?” You say with some good-natured bluster, “Well, I’d have to kill you, honey.” But suddenly she’s in no mood for levity. “You’d kill me?!” Her voice rises, she shrinks away, tears appear in her eyes. “Well, it wouldn’t be you, really.” “But you just said ‘I’d have to kill _you_.’ ‘You.’ That’s me! You want to kill me!!” By now we’re in melt-down-land, and you have to find a way out: “No, no, no, even if aliens took over your body, I’d never kill you, as long as it was you. You’re my pumpkin! How could I kill my pumpkin?!” (If you’re wondering, yes, I’ve had this conversation, and it wasn’t fun.)

That’s the Paul-Holder exchange. There is a difference. In the above scenario, the wife wasn’t already convinced the husband wanted to kill her, but now that he’s said he would, she’s beginning to think so, and it’s frightening her.

For Senator Paul et al, they long ago decided the government wants to kill them, and they’ve expanded that conviction into an entire philosophy. So, when Holder says, “Yes, that might happen,” Paul hears the malevolent beast of his nightmares arrogating to itself the right to kill him, and if it has the right, no matter how remote, it will do it.

This is what we see over and over: “Wait! If the government can order me to buy health-insurance, why can’t it force me to buy broccoli?! If it can tax my income at whatever percent it thinks is right, what’s to stop it from taking 100%?!” And so on.

If you’re living inside the wacko bird-funhouse, this makes perfect sense. Government sneaks into your life by way of innocent looking precedents, but once it’s gotten you to swallow one, no matter how small, your enslavement is inevitable. Because that’s how government rolls, you know. It’s like Jane Curtin’s ear: On the outside it’s all cute and pretty, but inside it’s dark and scary and filled with some kind of stuff we don’t know what it is.

On the other hand, if you’re Eric Holder and used to living in the reality-based community, you don’t even see this coming. The conversation starts with your being asked ‘if the government could under some remote circumstance kill an American citizen,’ and you say ‘yes, I suppose so, but we have no plan to do so,’ and befoire you know it your interlocutor is freaking out and shrieking about Hitler coming and killing him at a cafe for disagreeing with him, and now he’s shouting, ‘how do I know you’re not Hitler?!’ and you say, ‘calm down, I’m not Hitler,’ and so it goes.

The odd thing is that Paul was willing to accept a verbal assurance from Holder to the effect that he’s not Hitler. Odd because, after all, what would Hitler say?

It looks as if I spoke too soon. Senator Paul, having considered the matter further, has decided he’s not, in fact, happy with Holder’s reply. He embeds his current unhappiness inside a mini-memoir of his Jimmy Stewart-moment published by the Washington Post:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/sen-rand-paul-my-filibuster-was-just-the-beginning/2013/03/08/6352d8a8-881b-11e2-9d71-f0feafdd1394_print.html

“this debate isn’t over. . . . The president still needs to definitively say that the United States will not kill American noncombatants.”

Apparently Paul’s determined to get a statement from the president himself. Holder won’t do.

“The Constitution’s Fifth Amendment applies to all Americans; there are no exceptions. . . . ”

Again, he seems to have realized that a promise not to zap “an American not engaged in combat on American soil” is a tad ambiguous, and might actually be a statement of resolve on the part of the attorney general to begin whacking many of the junior senator from Kentucky’s supporters. After all, as Paul modestly confesses, “Americans are looking for someone to really stand up and fight for them. And I’m prepared to do just that.” See? Notice that word, “fight”? Isn’t that synonymous with “combat”? Isn’t Senator Paul in the cross-hairs now–and just for saying he shouldn’t be in the cross-hairs?

Now, you might say, being in the cross-hairs isn’t so bad–you don’t think they’ll actually pull the trigger, do you? Oh, you poor innocent thing you.

“On Thursday, the White House produced another letter explaining its position on drone strikes. But the administration took too long, and parsed too many words and phrases, to instill confidence in its willingness or ability to protect our liberty.”

Note that well: too much of that infernal Yankee parsing! They’re tryin’ to trick us! We can’t trust them! Forget that stuff about how “the president still needs to definitively say that the United States will not kill American noncombatants”!

Taking too long and parsing too many words and phrases is evidence of the administration’s unwillingness to protect our liberty. This isn’t an argument over _how_ to protect liberty, or about _what might_ have to be done in really extreme and difficult hypothetical cases where, say, a general has eaten too much falafel and gone rogue, and only the president and a single drone is left to protect America.

No, this is about the heart. The president’s heart just isn’t in it. So, if no matter what the administration says–more parsing, more words, more phrases . . . enough with the talk!–we can’t trust them, what to do?

“Americans are looking for someone . . . And I’m prepared . . .”

John Haas is entirely correct. In political discourse, one assumes the goodwill of the other. One must assume that the other party is concerned with the common good but they are in error regarding either where the common good lies or in the means to achieve the common good.

If one believes that the Govt is incapable of making correct determination of enemies, the situation is very serious and one has now uttered the revolutionary thought. That is, one has passed from political discourse to a revolutionary discourse. And once one passes this threshold. it is rather silly to ask for reassurances from the same Govt.

If one believes that the Govt is incapable of making correct determination of enemies, the situation is very serious and one has now uttered the revolutionary thought. That is, one has passed from political discourse to a revolutionary discourse. And once one passes this threshold. it is rather silly to ask for reassurances from the same Govt.

No one believes the Govt is “incapable of making correct determination of enemies.” The issues are that the “correct determination of enemies” requires due process in the case of American citizens and whether drones are imprudent considering the fallibility (not incapability) of the system.

It falls on the President to wage war and thus it falls upon him to identify the enemy and then take suitable action.

So either if Congress declares the territory of USA to be a war zone or the President belives that an attack is imminent (as on 9/11), the President is authorized to take suitable action against enemies he is authorized to identify.

It is a part of the logic of a republic that people must defer to the Govt that it has correctly identified the enemy. If you say that you do not trust the Govt to correctly identify enemies, that is, the Govt is unable to distinguish between people that may be killed and people that must not be, then you are alienated from your Govt in a very fundamental way. A nation is a community of friends united in a common love. And the alienation contradicts this community. Thus, you must presume in the goodwill of the President.

Art Nesten writes:

“No one believes the Govt is ‘incapable of making correct determination of enemies.'”

I’m not sure that’s quite right, Art. I imagine that there’s a lot of people reading this–and even more elsewhere–who believe the government misidentified the seceded states of the 1860s as enemies, and thus launched an illegal and immoral war that resulted in hundreds of thousands of needless deaths, wrecking the Republic and replacing it with a tyranny.

Indeed, I imagine a lot of the concern we’re hearing from Senator Paul et al is closely related to this belief.

And, in fact, one might think about whether the government correctlyidentified anemies during moments such as Japanese internment, or when the FBI infiltrated civil rights and snti-war groups, and such.

“The issues are that the “correct determination of enemies” requires due process in the case of American citizens and whether drones are imprudent considering the fallibility (not incapability) of the system.”

I believe one can grant the fallibility of the government and still wonder what all the ruckus about drones is about?

I do not trust the government tonever make a mistake. The Tonkin Gulf Resolution was a mistake; the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution was a mistake. But as those cases illustrate, “due process” doesn’t always get you much.

Rather insofar as there’s trust, as Mr. Iliaci has pointed out, it’s in the government’s “goodwill.” Such trust is not absolute, it can be (and I would say has been) betrayed. But inthat case, asking for promises from the government not to betray that trust, as Senator Paul has done, is rather bizarre. He subsequently walked back his expressions of satisfaction with the Holder letter, and said “the administration took too long, and parsed too many words and phrases, to instill confidence in its willingness or ability to protect our liberty.” Note that scepticism towards the administration’s “willingness” to do the right thing.

The government/president has always asserted the right to eliminate enemies anywhere, and it reserves to itself the right to determine who counts as an “enemy.” Whether one uses a drone or a sniper or whatever is immaterial. As our history shows–especially when dealing with “enemies”–the president has little difficulty corralling the other branches of government and society into acceding to his will. The one unelected branch has at times pushed back, but their deliberations take time and no president would restrict himself to acting in emergencies only after the Supreme Court had authorized that action–nor would the Supreme Court want that authority, nor would such a solution be Constitutional.

A lot of commentary on ‘imminent attack’ is due to confusion between a law-breaker and an enemy. This confusion naturally arises in minds that see State as a collection of individuals. That is, they deny that State is an irreducible (along with Family and Individual).

The enemy seeks to subvert the State. A law-breaker does not.

Now when you have reduced the State to Individuals, you lack a firm understanding of ‘enemy’ concept and it gets confused with ‘law-breaker’.

Then you start with Is that person actively trying to kill some other persons?. Should the police apprehend him or should Army deal with him?.

Practically, the people in charge will always do the necessary deed (since these things are intuited even by a smallest child) but unless the vision is clear, the nation would be saddled with a needless controversy.

“they deny that State is an irreducible [thing?] . . .”

Mr. Iliaci, here we need to make some distinctions. The USA has “states,” but the federal government isn’t actually a “State” in the European sense.

Our Constitution grounds sovereignty in the people, and that sovereignty is limitless–it extends to every aspect of the government. There is no limit to what we may add to the Constitution by way of amendment, or take away, indeed, we may repeal the entire Constitution if we so wish. As for the representatives who make decisions, they serve entirely at the peoples’ will. They can be voted out of office, or removed prior to that, should the people wish.

All of that means that while we ask the federal government to perform the functions of a State, we do not regard it as one, and so do not accord it the kind of respect one finds in many other societies. For good and for ill.

A distinctively American solution to the problem of domestic drone strikes isn’t for Americans to adopt European-style attitudes toward their government. They won’t and they never will.

It’s to rely upon and encourage the sovereign people to make sure that this awesome and terrifying power isn’t misused in ways the people do not and should not approve.

Mr Haas,

“the federal government isn’t actually a “State” in the European sense.”

Naturally, as no Govt is State. By State, I mean, following Aristotle, a particular self-ruling authoritive moral community i.e. an organized society- a society with an army and a navy and a Judge. The judge is all important since the hallmark of a State is that it metes out justice.

An individual can not lawfully punish another individual. If someone steals from you, it is lawful for you to take the stolen things back but not to flog the thief.

From this perspective, America is nothing special.

“Our Constitution grounds sovereignty in the people”

Per Belloc (The French Revolution), the sovereignty is always grounded in the people. It is there in the first chapter where Belloc explains the Political Theory of the Revolution. He calls this theory eternal and true.

“America is nothing special.”

Right.

It’s exceptional!

Comments are closed.